Streaming on: Netflix

Episodes viewed: 8 of 8

It feels appropriate, somehow, that Tom Ripley, the ever-chameleonic con man created by author Patricia Highsmith, has proven a bit of a chameleon on screen. Over the years, the character has been played by the likes of Alain Delon, Dennis Hopper, John Malkovich and (perhaps most famously) Matt Damon. The last, in 1999’s The Talented Mr. Ripley directed by Anthony Minghella, cemented Ripley in contemporary minds as a sexy, sun-dappled anti-hero, indulging in misplaced romance, murder and mystery on Italy’s Amalfi Coast: Eat, Slay, Love, if you will.

Now along comes Steven Zaillian, screenwriter of Schindler’s List and The Irishman, adapting the same original Highsmith book as Minghella, bringing an entirely new flavour to an old psychological thriller. It’s a fascinating exercise in interpretation and execution: the plot and narrative are near-identical to all the previous takes on this material, but the look, feel and tone are wildly dissimilar.

Most strikingly, Zaillian — who writes and directs every one of these eight episodes, a rare TV auteur — has swapped the warm, glowy colours of Minghella’s Mediterranean sunsets for some severe, stunning, black-and-white cinematography, courtesy of Paul Thomas Anderson’s former director of photography, Robert Elswit. In an era where huge TV budgets often equate to cheap-looking visuals, Ripley is staggeringly, starkly beautiful.

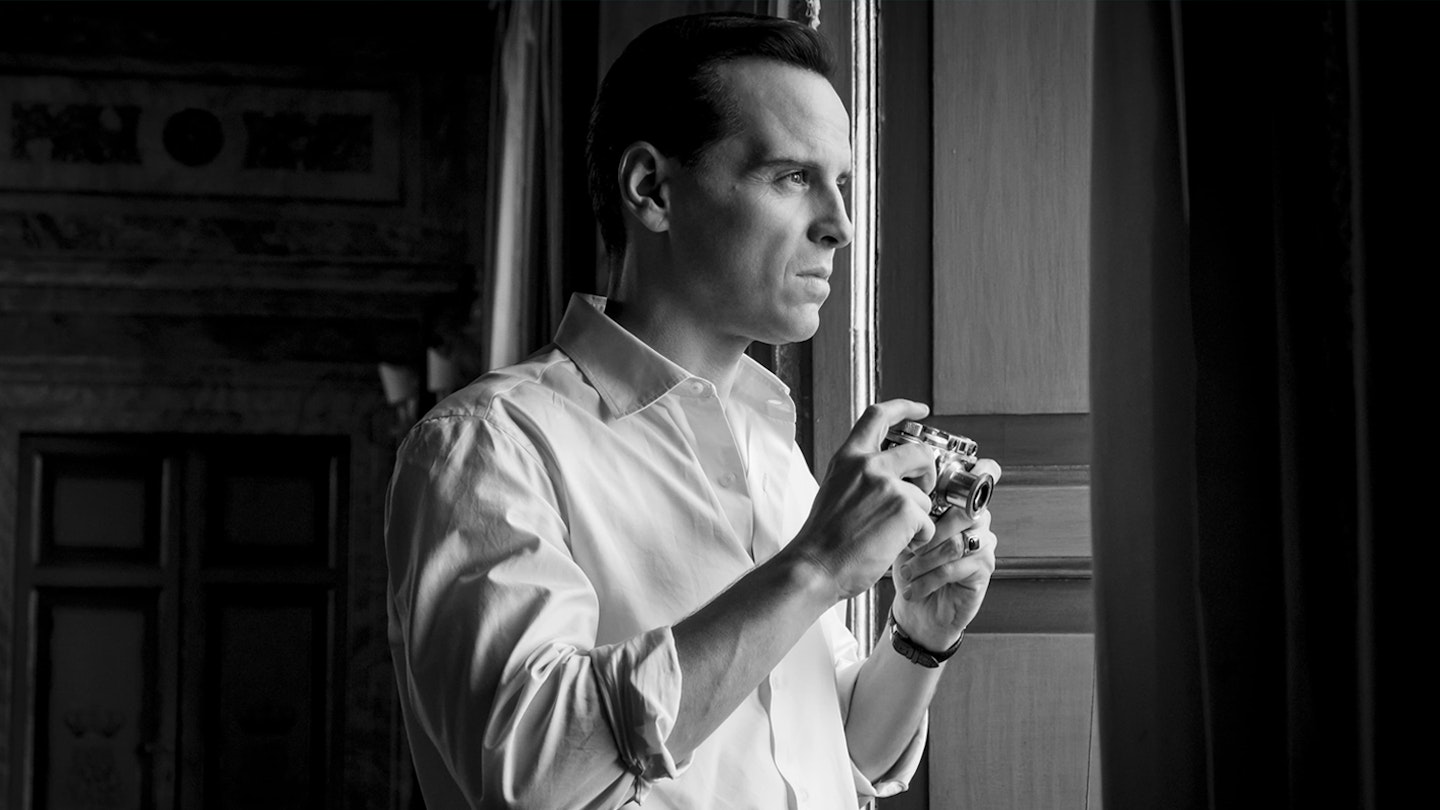

Andrew Scott offers a markedly different Ripley than any we’re used to.

Recalling Cold War-era film noir like The Third Man or Touch Of Evil, there is compelling craft here for days: exquisite framing and composition, expressionistic lighting, Dutch angles, dark corners, brooding scenery, endless intrigue. Zaillian’s camera establishes and stresses the moody, mysterious tone by finding visual tension in an outwardly beautiful place: there are jarring close-ups of a creaky-old-bus gearstick, looming overhead shots of staircases or sheer cliffs, pointed cut-away shots of gargoyles, and repeated plunges into the darkness below the surface of the ocean.

It’s a fresh visual grammar matched by a fresh approach to its cast. Andrew Scott — who only last year was so extraordinarily humane and vulnerable in All Of Us Strangers — offers a markedly different Ripley than any we’re used to: gone is the smoothness of Delon or the boyish charm of Damon. His Ripley, an established grifter from the start, is a cold-blooded bastard, the psychopathy immediately on the surface; when a certain famous scene involving a boat trip arrives — a true oar-deal — Ripley’s face is impassive and unmoving.

As hapless Dickie Greenleaf, Johnny Flynn has a less playboyish take than Jude Law, too, grounded and cooly charismatic, channelling a young Robert Redford. The relationship between Dickie and Ripley here is one of detached curiosity rather than excitable bright young things, an odd couple observed with icy understatement by Marge (Dakota Fanning, who can sip a martini and somehow make it seem like a slight).

The queer undertones of Ripley’s character are directly addressed in this adaptation, Zaillian making explicit what was always largely implicit. (“I like girls,” Ripley assures Dickie, almost defensively.) But his motivation here seems less misguided romance, more a man haunted by the death of his parents, and one easily affronted by the slightest cold shoulder.

Zaillian makes the most of the long-form format here, luxuriating in the time spent with this psycho, and there is an assuredness to the slow unfolding of it all, especially when Maurizio Lombardi’s Inspector enters the fray (every bit the mirror of Bill Camp’s detective in Zaillian’s superb miniseries The Night Of). That pace somewhat slows in the middle of the series, with at least one episode devoted entirely to the grisly rigmarole of disposing of a body, in painstaking detail. In one scene, Ripley sighs, irritable at the elbow-grease required for a murder; you may sympathise.

Inevitably, this is a less obviously inviting take on this tale. It is darker, literally and figuratively, and Tom Ripley — so often the scoundrel you love to hate — is less paradoxically likeable here than ever. But it is rare to find television this genuinely ambitious or finely tuned. Throughout the series, Zaillian makes references to Caravaggio, one of Dickie’s favourite artists; he and Ripley visit his grisly painting ‘David With The Head Of Goliath’: a baroque, beautifully crafted vision, much like this adaptation.