Trying to make a thriller about jazz is like trying to make a horror about puppies; you are starting with a subject that inspires, in most people, the exact opposite of the emotion you’re going for. Yet Damien Chazelle has done it. With just one short and one feature on his imdb page, he has made a heart-thumping drama about percussion. He has made a sports movie with no sports, but plenty of balls.

In the tradition of great thrillers it has an ordinary man trying to best a much trickier foe, and like great sports movies it has a rookie intent on winning everything. It just finds those things in a place nobody usually looks. Andrew (Teller) is a talented, but cocky, drummer who wants to join the best band at his music college. The only way to do that is to catch and hold the eye of Fletcher (Simmons), the conductor/coach, who expects those on his team to meet his high standard or get the hell out. And why shouldn’t that be thrilling? Tension is just hoping for the best while expecting the worst. Chazelle yanks your heart into your throat waiting to see if a man will nail a drum roll, because he directs like everything’s at stake. In the music room his camera flashes around catching blood, sweat and tears. Andrew drums until his skin cracks open. Nothing is still. Nobody is settled. You’ll probably leave the cinema in need of a massage.

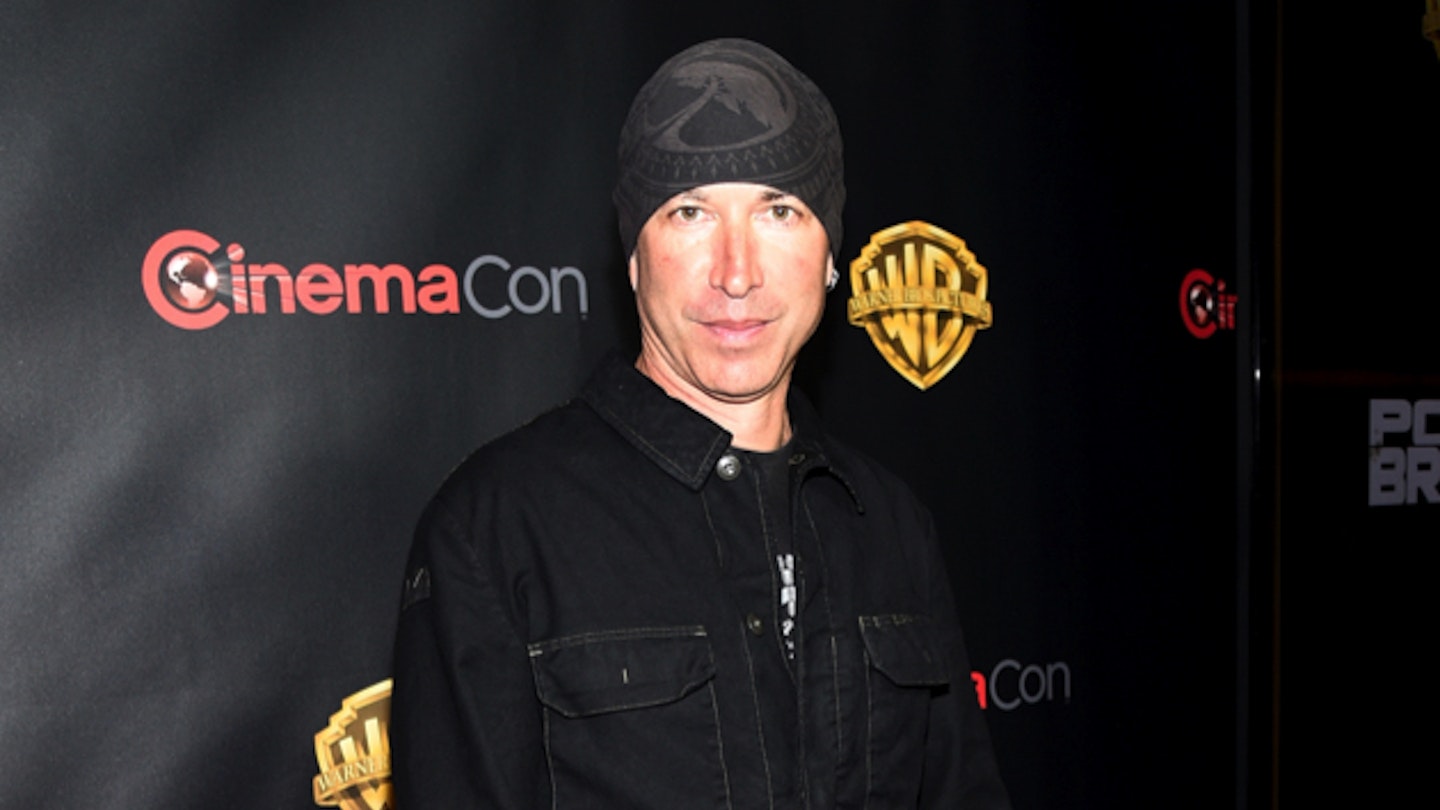

Taking nothing away from Teller’s all-in performance, this is Simmons’ film.He’s always been one of the best, but now, finally, a script has caught up with him. Fletcher’s a rumbling, black-clad storm of a man, ready to rain hell down on Andrew when he’s less than his best. And Simmons really relishes those moments, barking out lines like, “If you deliberately sabotage my band, I will fuck you like a pig". He’s terrifying, yet not really a villain. Chazelle keeps the roles shifting. Is Fletcher, who believes in rewarding greatness not effort, worse than Andrew, who believes wanting is the same as deserving? We never know for sure whether Andrew is as good as he believes he is. It pulls you in, tighter and tighter, by asking you to constantly see the other side.

Whiplash is so close to faultless that its one stumble is frustrating. Having kept its rhythms perfect for the entire first hour it bangs a bit too hard when Andrew reaches his breaking point, proffering up about five minutes that stretch the bounds of dramatic credibility. The film doesn’t need obvious melodrama because it’s shown how much you can make without it. But five minutes of self-indulgence and another 100 of ovation-worthy hits is a great ratio for any performance.