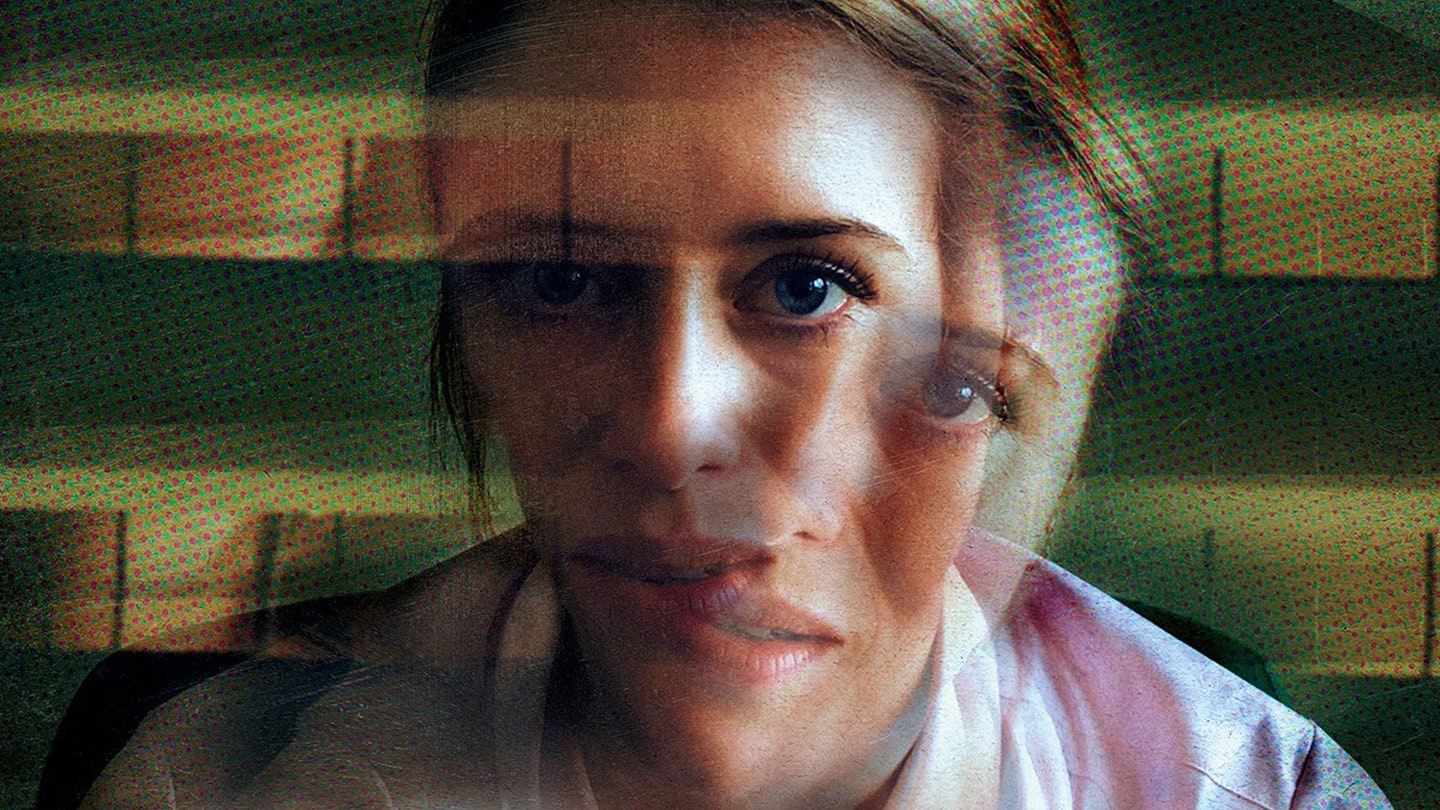

Featuring medical malpractice, reality-smudging prescription drugs and a female protagonist who may or may not be losing her sanity, Steven Soderbergh’s second post-‘retirement’ production lurks closest to his second-to-last pre-‘retirement’ movie, Side Effects. But where that was executed in the glossy style of a typical Hollywood thriller, Unsane is down, dirty, lo-fi and — no doubt made for a nickel and a dime — commercially uncompromised. Meaning that once Claire Foy’s apparently fragile Sawyer finds herself incarcerated in an unscrupulous psychiatric hospital then tormented by a demon from her past, we’re taken somewhere far more nightmarish and murkily disturbing than the director’s ever led us before.

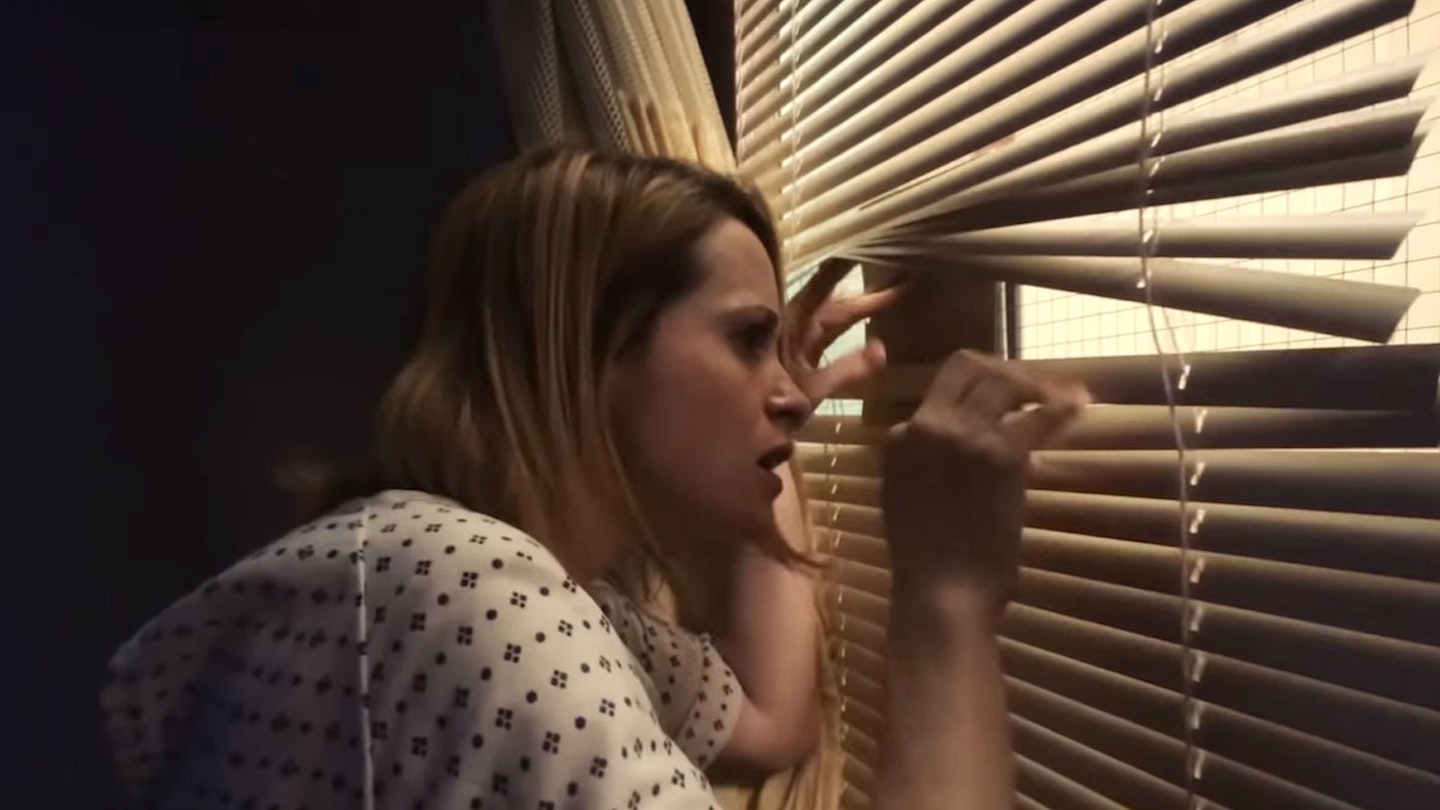

With the entire film shot on iPhones, it would be all too easy to write it off as a flagrant act of gimmickry on Soderbergh’s part. This is, after all, the filmmaker who once shot a movie (2006’s The Good German) in the style of Michael Curtiz — but with sex and swearing — and whose nuts-sounding HBO project Mosaic comes with a narrative-influencing app. But his creative decision for Unsane really nourishes the mood of nasty, queasy unease. The image quality is cold and grainy, feeling surreptitiously snatched rather than framed, and lending a sense of grubby voyeurism to the experience. Something that’s exacerbated by the low angles (one date scene is captured by a phone propped on a bar, making you feel like a little you’re watching while trying to crouch out of sight) and personal space-invading POV close-ups.

Unsane feels more closely related to Get Out than any previous Soderbergh movie.

It’s all horribly appropriate for a narrative threaded around a woman whose life has been shattered by a stalker. And smartphones, of course, are the stalker’s best friend. As an anti-stalker advisor (played by Soder-friend and cameo-addict Matt Damon) tells Sawyer during a flashback scene, “Think of your cellphone as your enemy.”

In a sense, Unsane feels more closely related to Jordan Peele’s Get Out than any previous Soderbergh movie — Get Out being a film Soderbergh has praised for dealing with social issues through genre cinema. Jonathan Bernstein and James Greer’s script doesn’t share Peele’s sense of humour — this is, without any doubt, grim viewing — but the Get Out creator’s definition of his film as a “social thriller” (rather than ‘horror’) does fit Unsane perfectly.

However, the target here is not corrupt medical institutions. In fact, the idea that a hospital would repeatedly entrap unwilling patients in order to cash in on their health insurance pay-outs feels a little far-fetched. Thankfully, Sawyer’s institutional entrapment is a scene-setter rather than the main thrust of the plot, providing a grey-walled cage from which she needs to escape and a set of damaged supporting characters for her to rail at and bounce off while the true threat gradually becomes clear.

What the film really takes aim at is sexual abuse, as it manifests across the spectrum. Before she’s committed, before things get extreme, Sawyer is leered at by men on the street and inappropriately propositioned by a creepy boss. Then, once the hospital’s trap is sprung, she is horrifically gaslighted and more straightforwardly tortured by someone who, whether real or a drug-induced phantom, sees ‘love’ as a justifiable act of possession.

It’s tricky, prickly territory, not least because the question mark the story dangles over Sawyer’s head requires us to wonder whether or not she’s suffering at the hands of a real man or her own psychosis. In other words: maybe she’s to blame, even if it is as a result of illness. But Bernstein and Greer’s script keeps its balance, while Soderbergh keeps things on the right side of exploitation, and none of his shocks come fringed with the kind of intended titillation you’d expect to find in a conventional horror.

To pull it all off, the director couldn’t have made a better choice for his lead actor than Foy. Having grown used to seeing her regally restrain her emotional responses in the likes of Wolf Hall and The Crown, we get to witness what she can do when she’s furiously unleashed. This is about as far from the stifling, hi-def opulence of Buckingham Palace as it’s possible to imagine.

It’s a blistering performance, one that was no doubt intensely uncomfortable for Foy, but one in which she ensures Sawyer is neither dismissible as ‘hysterical’ or ever reduced to a whimpering victim who only requires another man to rescue her. She is horribly wronged. She is bruised and battered, both emotionally and physically. But she is never completely broken. “There is no path to happiness from here,” Sawyer says at one point. But there might, whatever the cost, be a path to justice.