Around the 20-minute mark of Jon Shenk’s miraculous documentary, The Beginning, about the making of Episode I, the true villain of The Phantom Menace makes a cameo appearance. You can glimpse the shadowy figure lurking in the background as Ewan McGregor gets his Padawan buzz cut. His name is Jett Lucas, adopted son of George, and seasoned Star Wars apologists should take note of his most insidious characteristic - he is around the same age as Jake Lloyd’s Anakin Skywalker.

A great many fluffed details derailed the most anticipated movie of all time, but the miscalculation that undermined the entire prequel enterprise was George Lucas’ insistence that when we first meet the future Darth Vader he is a little boy who cries when he is separated from his mother. Lucas risked his legacy based on a father’s simple conviction that bad things can happen to good people and a divorcee’s guilt that children from single parent families are more vulnerable than most.

To make his point painfully obvious Lucas arranges the action of his first movie since his separation from Marcia Lucas in 1983 around the discovery of a miracle child by a doomed father figure and the eventual passing of this boy from his natural mother to an adoptive parent who is perhaps not yet mature enough to master the task alone. But to accommodate this one action Lucas is forced to postpone every other key event to a later movie – how could a nine-year old participate in the Clone Wars? – and effectively botches up his starting position. It is a mistake from which the prequels never recover.

Things get off to a cold start with the much parodied credit crawl. Where Episode IV goes for the in media res jugular – “It is a time of civil war!” - problems in Episode I are not quite so pressing. Events are “alarming” perhaps, there’s certainly plenty of “turmoil” and we all know “taxation” is a thorny issue but the context is clear: like Anakin, this conflict still has some growing up to do. The menace is still phantom.

An inexcusably lazy establishing shot - the Jedi shuttle cruises past the camera - and lethargic opening sequence hardly help pick up the pace. In A New Hope’s famous opening salvo the bad guys fire first and ask questions later, in The Phantom Menace the Jedi are ushered into a meeting room while the semi-bad guys go into video conference with Darth Sidious about whether an invasion of Naboo is legal or not.

This arse-numbing inactivity recurs throughout The Phantom Menace: because the battles lines are not yet drawn and sides are still being taken there is always much explaining to be done, characters are forever having update meetings or being introduced to one another. The plot machinery lumbers through the gears, hampered further by the strange declarative dialogue and by an apparent disinterest in making these scenes visually interesting.

Critics complained that Lucas had got yet worse at writing for humans in the twenty-two years since Star Wars, in fact it is simply that, beyond Alec Guinness talking about the force, the plot of A New Hope requires no exposition - The Phantom Menace on the other hand is all explanation, much of it, like the midichlorians, unwanted and unnecessary. (To be fair, Lucas waited a generation before spoiling his enigmatic myth with background material, the Wachowski’s jumped that particular shark in film two.)

And yet there is still much pleasure to be had watching our full-blown Jedi guides in action. Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan quickly discover that things are mercifully worse than the credit crawl predicted, a robot invasion force is being unpacked, Naboo is under actual threat. Sadly, we never actually see any of the massacres that are apparently taking place, instead we land somewhere that looks suspiciously like the woods near Leavesden and meet one of the galaxy’s more annoying comedy sidekicks (although not as annoying as fans frantically searching for a scapegoat would have you believe). After all, this film has at its hero a small boy – it cannot visit the dark 12A places.

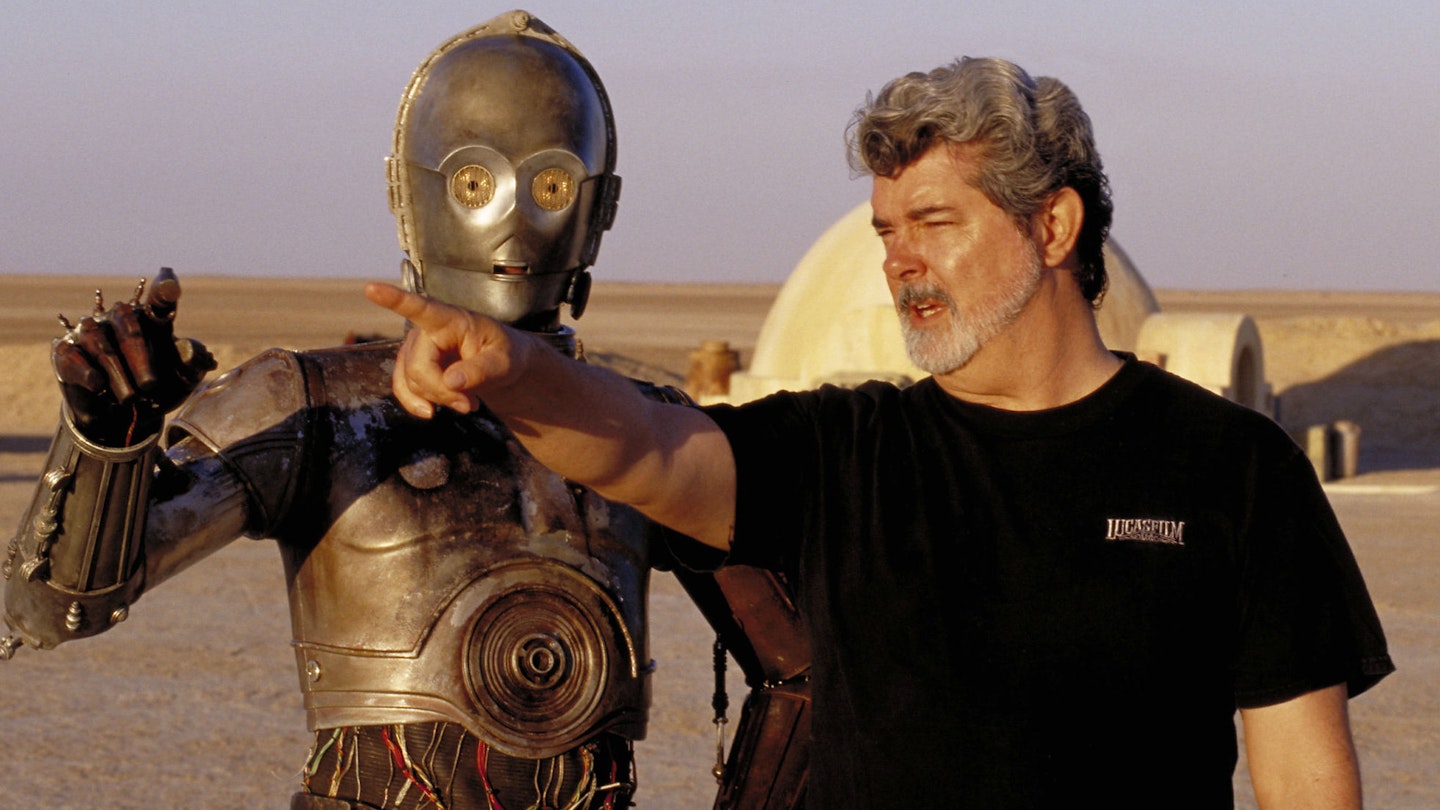

What Lucas later confessed was a “jazz riff” of a plot wafts our heroes to the holy ground of Tatooine, all sense of urgency dissipated. In A New Hope Luke and Ben, heading the other way, are already too late: Alderaan is gone. From that moment it is a race against time (collapsed to provide greater unity) and a struggle just to stay alive. In The Phantom Menace our heroes are waylaid by a faulty engine. Hmm. The fate of the galaxy hangs in the balance and Qui-Gon prefers to gamble with a junk-yard dealer than twat him with his lightsaber.

Tatooine turns out to be a total bust. They leave Obi-Wan behind, Amidala pretends to be Padme for no good reason, Anakin whines a lot, there’s some mumbo jumbo about a mystical birth and at absolutely no point does Han Solo turn up. Bastard. This is a section so flabby that even the electrifying pod race goes on for one lap too long.

But hell, we meet Vader Jnr. and he says goodbye to his mother, which is the only essential action of the movie, so it’s almost worth the trip.

Despite the unspeakable Yoda puppet, more endless politicking and some iffy CGI, the arrival on Coruscant and the subsequent battle of Naboo provide most of the lasting excuses for forgiving The Phantom Menace. At last there are new worlds to explore, new creatures to encounter and new wrinkles to the Star Wars myth. On Coruscant we are free to marvel at the work of Doug Chiang’s design department - every bit the equal of the original trilogy. And during the saga’s very best lightsaber battle John Williams adds another classic theme (Duel Of The Fates) to his masterpiece. The final act is a mess of conflicting ideas and we are forced to root for a tweenage space pilot but you certainly can’t fault it for pace.

Perhaps best of all, we have the death of Qui-Gon. Liam Neeson has manfully carried the action on his shoulders throughout (the subsequent prequels desperately miss him) and his final words – “Obi-Wan, promise... Promise me you will train the boy” - provide the movie with its only real weight.

Lucas probably imagined that Anakin’s goodbye would be the real heartbreaker but he couldn’t write it and Jake Lloyd couldn’t act it. The irony is, we don’t need it. Given where he is destined to end up, Anakin doesn’t need to be innocence personified when we meet him. Indeed, we are told that the kid is too old to be trained and that the Jedi council fear him, facts that are utterly lost on an audience who see only a bowl-headed brat.

And yet if only Lucas could have stopped thinking like a fearful father and acted more like the fearless myth-maker of old, there’s a quick fix that would change everything. Imagine for a moment a street urchin orphaned by the Clone Wars, a scoundrel scamming to survive, already using the force without even realising it. Imagine a cocky fifteen-year old robbing Qui-Gonn, competing with Obi-Wan and flirting with Padme. Imagine, for a second, an Anakin invested with the spirit of a young Han Solo…