We know what happened when the unstoppable force of Walt Disney met an immovable object, Mary Poppins author P. L. Travers; the perennially popular film that resulted stands testament to the fact that she finally signed over the movie rights. But like Frost/Nixon or 300, knowledge of the outcome doesn’t preclude fascination in watching the battle, and this story of clashing artistic cultures remains evergreen. At face value, this is the story of a highly introverted and controlling woman, haunted by childhood tragedies, who is finally won over and loosened up by the irresistible appeal of Disney’s creative team and the mogul’s own good offices. But thanks to its two stars, a wealth of nuance and subtlety makes this a richer story than it first appears.

In her small and over-stuffed London home, Travers’ agent warns her that she’s out of money and cannot afford to keep ignoring the 20-year campaign by Walt Disney to secure the rights to Mary Poppins. Emma Thompson’s Travers irritably rejects such considerations out of hand, but visibly weakens almost as soon as the ultimatums are out of her mouth. Her head may occasionally be in the clouds, but Travers’ feet are so firmly on the ground that she can never deny reality completely. Ultimately, then, this is less about Disney convincing her to do something she doesn’t want to do, and more how Travers deals with her own misgivings over what she already knows she must.

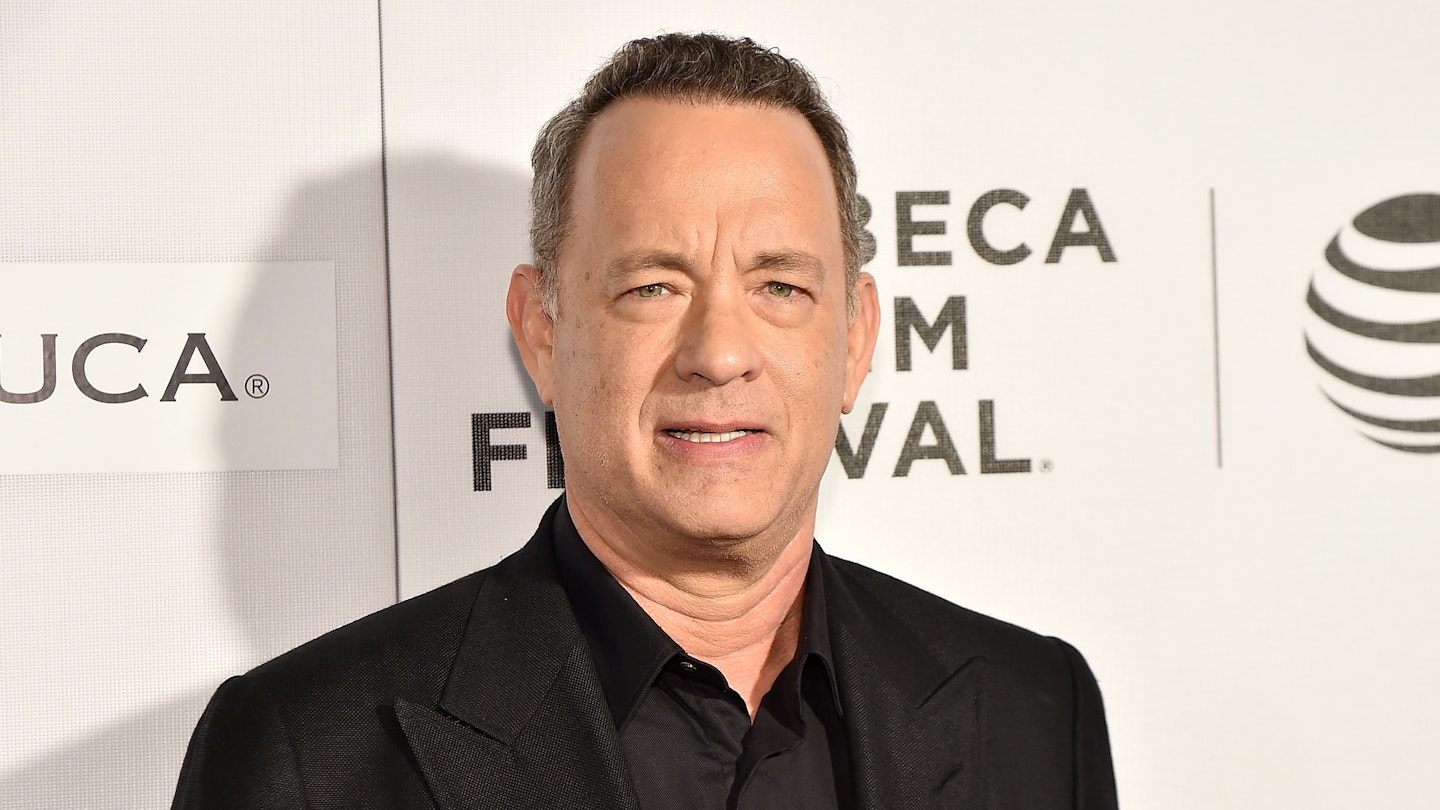

While the trailer suggests a two-hander between Thompson and Tom Hanks, the reality is that this is her story and his is a smaller, supporting role. Thompson is instantly magnetic, delivering hilariously cutting put-downs with such blithe disdain for everyone and everything that she never quite crosses the line into bitchiness. Her saving grace is that Travers’ merciless insight extends to her own life as well, clearly making her deeply unhappy.

But the unreasonable demands she makes of Disney and the minions he assigns to keep her sweet — driver Ralph (Paul Giamatti), screenwriter Don DaGradi (Bradley Whitford) and songwriting Sherman brothers Richard (Jason Schwartzman) and Robert (B. J. Novak) — are parries in her skirmish with Walt, on some level mischievous rather than malicious, although that’s probably small comfort to her victims. Highly guarded and inclined to suspicion of all things Disney — she even insists their script conferences be taped for the record — she’s an acerbic delight, neatly skewering any attempt at cuteness, whimsy or even charm. Her exasperation with American values and Disney in particular is refreshing; it’s rare that cinema provides such a clear demonstration that the US and UK are two countries divided by a common language. Travers has no patience with Disney’s determination to “careen towards happiness like a kamikaze” and takes a deeply serious approach to the adaptation, while Disney looks in vain for the dreamer who wrote about a “flying nanny with a talking umbrella”.

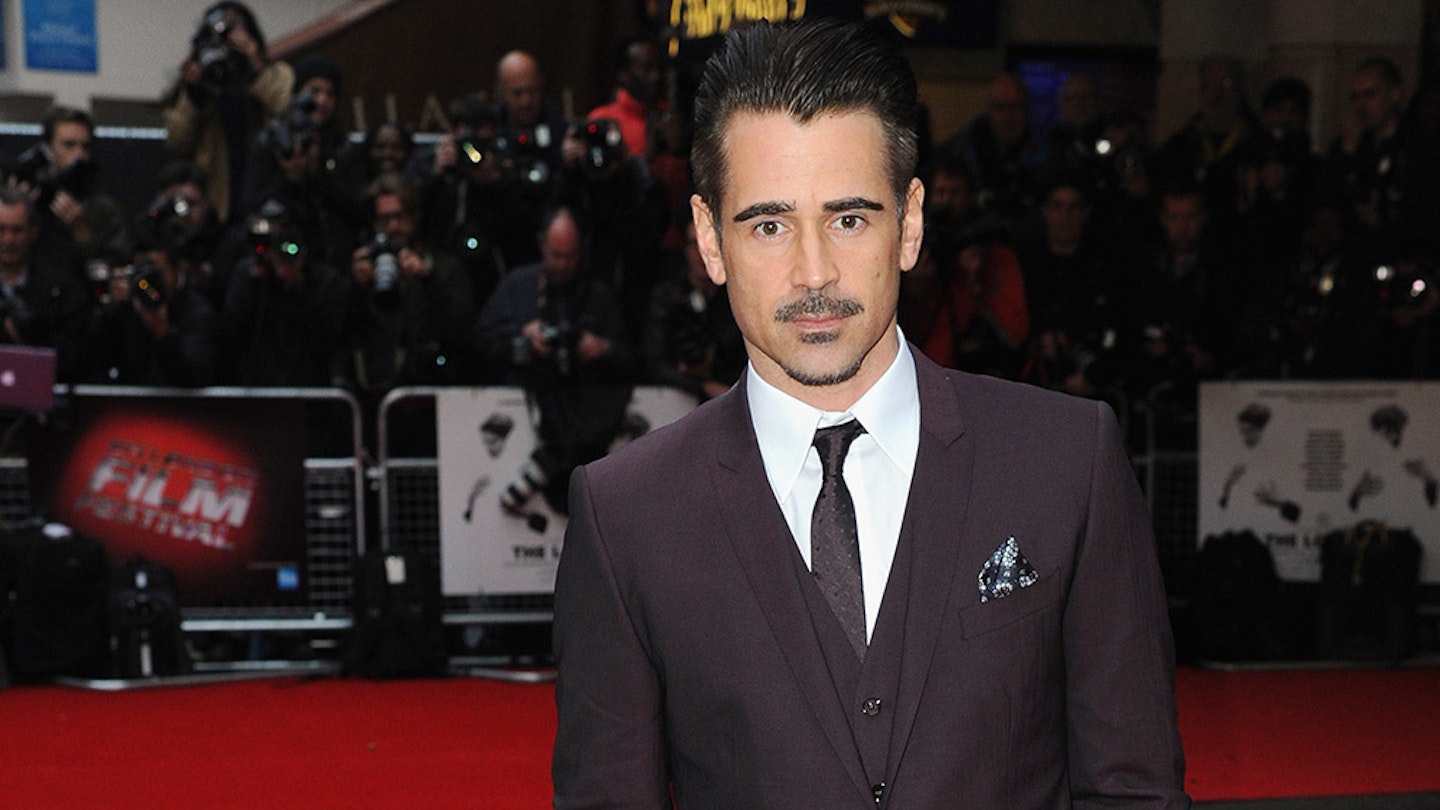

To explain Travers’ attachment to her book, and reluctance to trust her characters to a man she sees as more businessman than artist — not without some justification — the film uses extensive flashbacks to her childhood in early-20th-century Australia. We meet her dearly loved father (Colin Farrell), happily romping with his children even as he scandalises her mother — and much of the town — with his disregard for propriety and, it gradually emerges, heavy drinking. The young Travers (Annie Rose Buckley) understandably worships her dad as he spins fantastical stories and paints images of a magical world all around, but is not so young that she fails to realise that something is deeply wrong with him and soon with her mother (Ruth Wilson) too. No-one plays beautiful and doomed better than Farrell, and he adds real pathos to dialogue that could have been flowery. His accent occasionally wobbles, but that can be explained away: there are onscreen nods to his Irish roots, and in a meta sense perhaps he’s paying an obscure tribute to Mary Poppins’ Dick Van Dyke.

The film’s most serious shortcoming is that these flashbacks are overused, director John Lee Hancock not trusting his audience to read volumes in every twitch of Thompson’s eyebrows. That’s especially galling in the final scenes, when we don’t need dramatisations to know that Travers’ careful self-control is beginning to crumble, and why. It’s all in Thompson’s performance and even appearance — her tightly permed hair gradually loosens as the film goes on, a neat visual representation of her thawing resistance.

There’s further subtlety in Hanks’ turn as Disney. He uses his immense likability to play the showman and television star that the studio head was at this point, but has the gravitas and depth to show that jolly old Uncle Walt could also be ruthless. He encourages his employees to call him by his first name, but they also whisper warnings that, “Man is in the forest!” as he approaches. He is moved nearly to tears by an early stab at Feed The Birds, but reduced to helpless fury by Travers’ shenanigans. There’s something subversive in a Disney film portraying its founder in such rounded terms, and while he has some emotional scenes with Travers, we never forget he wants something from her.

Travers’ character is inevitably simplified, downplaying her standing as a poet (while Yeats is namechecked here, the real Travers actually knew him) and glossing over her adopted son, love affairs with both sexes and early career as an actress. She was not the buttoned-up spinster that the film indicates but rather a progressive and at times transgressive figure. The film occasionally shows a woman very much to be pitied rather than scorned, where the real Travers would scorn pity. Thankfully she remains biting to the last.

The story is strongest not in showing Travers’ genesis but the film genesis of her great creation. Travers was right to resist the addition of too much Disney magic, and that it retains an edge of real feeling is down chiefly to her efforts, in particular as regards Mr. Banks. But Disney was right to put it on screen, and right about the animated penguins. Sometimes a spoonful of sugar really does help the medicine go down.