This could be described as high concept Woody Allen, fixing the great comic writer’s familiar philosophical preoccupations into a strange fictional documentary of a man who has no personal shape of his own, instead taking on the guise of any larger ego nearby. Allen’s target is the pathology of the frail human psyche, how Zelig can only conform to what is around him, but whose complete inability to have a self makes him unique. Irony runs rife, and as the film stalks through history, shot in the style of those shuffling mock-aged newsreel edited together with the genuine articles, Allen skilfully weaves together the notion that Zelig is afflicted with an unknown disease — acute ordinariness, to an extent that makes him hugely influential, the anti-ego.

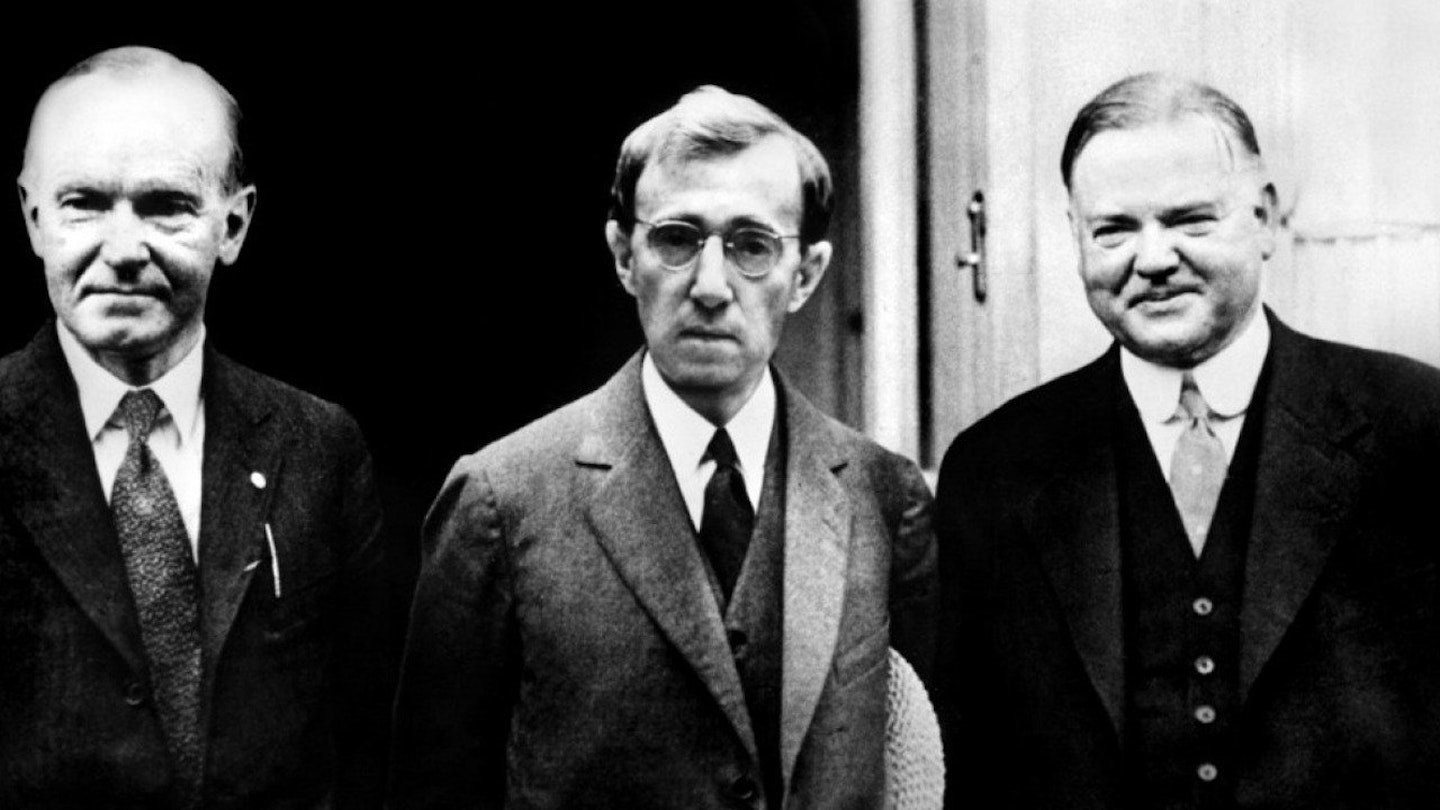

Zelig, played by Allen with both vacuity and versatility, plops in and out of history like a tumbleweed, every time a different person: an actor, a learned doctor, the son of a jazz musician. There is the teasing suggestion that, if anything, Zelig is exactly like an actor. Naturally, then, he becomes a celebrity, and is on hand at the pivotal joints of history itself from Babe Ruth’s winning runs to Hitler’s sinister rise to power. Allen is brilliantly superimposed into the archive footage, a chameleon, a trick later borrowed by Forrest Gump.

With Mia Farrow, starchy and poised, as the psychiatrist determined to cure him, the ‘20s setting accents the director’s examination of human psychology — it was in its ascendancy during the era. And in a further irony still — there the onion layers of meaning that can picked off the film — the Jewish director even makes fun at intellectual posturing and over-analysis by having such big brains as Susan Sontag, Irving Howe and Saul Bellow comment knowingly on Zelig’s dilemma.

Teeming with one-liners, humorous asides and references it is hilarious. The only problem the film faces is its own artifice. We are watching a hugely clever game that appears just that, impressive but mechanical. When the gears try to change — proposing that love could be the only answer to Zelig’s shapelessness — the film suddenly feels forced.