Epic in both scale and scope, Women Make Film is that all-too-rare treat: a documentary given ample time and space to delve deep into its subject. And despite its title (which could be both statement and a call to arms) and premise — a global exploration of movies made by female directors — Mark Cousins has resolutely not made a film about the female gaze, or one bemoaning the lack of women filmmakers. Instead, he takes the far more proactive approach of celebrating the myriad women who have made extraordinary films by presenting their work as a 14-hour masterclass of how great movies are made.

There is an early nod to the appalling gender imbalance that has motivated this incredible undertaking. “The film industry is sexist by omission,” says Tilda Swinton, one of seven narrators that also include Jane Fonda, Adjoa Andoh, Thandie Newton, Kerry Fox, Sharmila Tagore and Debra Winger. (They are often seen in cars, travelling down anonymous highways; this is an odyssey both literal and figurative.) “Film history has been sexist by omission,” continues Swinton, highlighting the fact that many female directors are routinely overlooked.

One can’t help but be moved by this wealth of cinematic mastery.

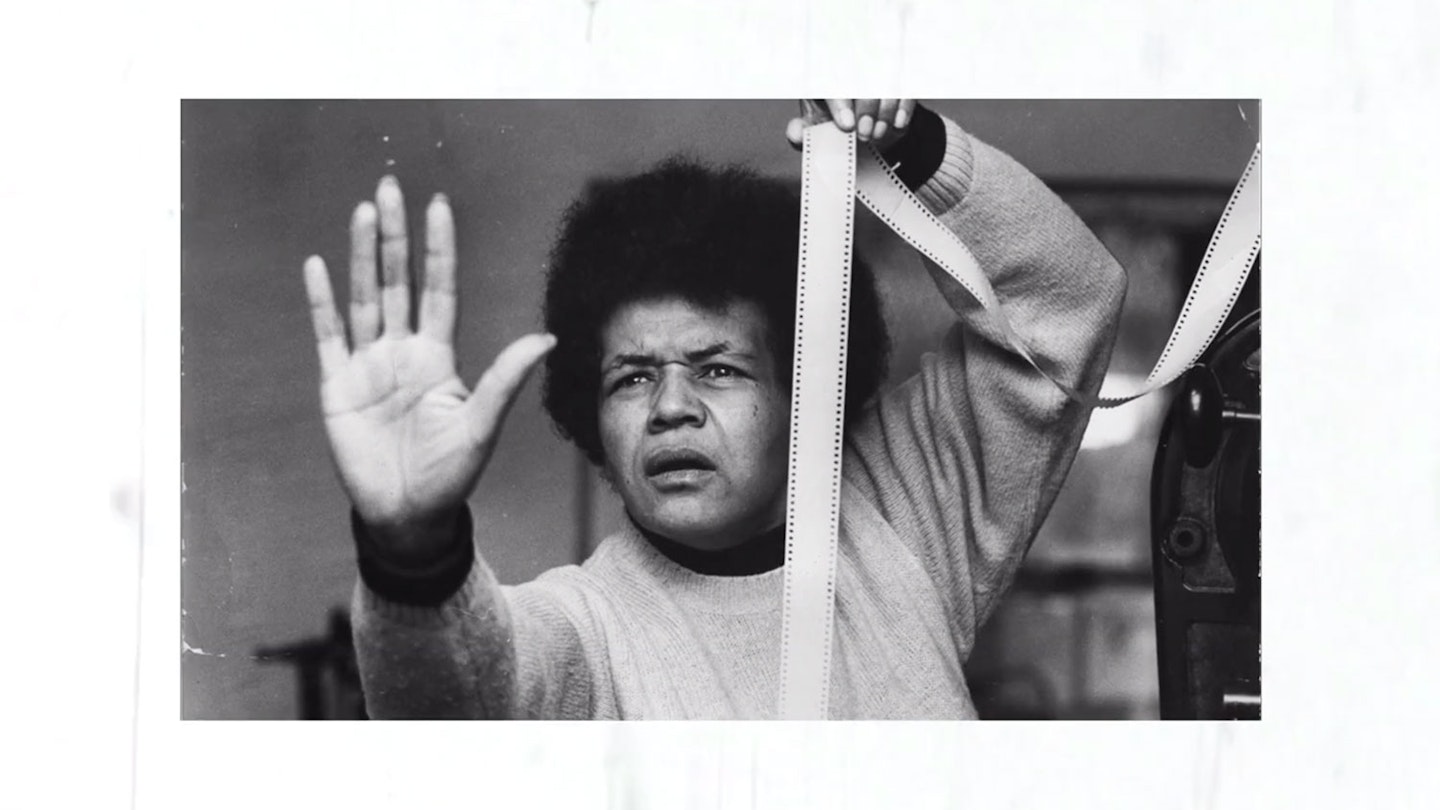

And so it is that each of the 40 chapters, ranging from craft skills (‘Framing’, ‘Editing’ etc) to genres to more thematic topics such as ‘Sex’, ‘Melodrama’ and ‘Death’, is packed with a plethora of women, from early Hollywood pioneers like Lois Weber and Dorothy Arzner to international filmmakers such as Japan’s Kinuyo Tanaka and Russia’s Yuliya Solntseva. And each of the 400-plus clips has been carefully selected to not only work on their own, highlighting each director’s style and approach, but also together; intricate puzzle pieces connecting to make a cohesive whole.

Take the section entitled ‘Journey’, for example, which features 20 filmmakers. Here, we see how Jennifer Kent’s The Babadook — one of several films to appear in multiple chapters — details its grieving protagonist’s struggle for acceptance as a journey into nightmare. In the same segment, Andrea Arnold’s American Honey deals with a physical journey, a car packed with youngsters becoming a microcosm for desire and freedom, while in Alice Guy-Blaché’s 1907 silent short Course à La Saucisse, a dog and a sausage turn a journey into a thing of mirth.

Crucially, too, elements from each chapter also interlace with others, earlier topics such as ‘Tracking’ and ‘Staging’ bleeding into our appreciation of subsequent sections. As the film progresses, individual strands weave into a complex cinematic tapestry which, as Kerry Fox describes, shows us the entire world. As images of the directors fill the screen at the end of the final chapter, one can’t help but be moved by this wealth of cinematic mastery, stricken by how many of these women have been forgotten and determined to seek out even more.