There’s no earthly reason why a studio of Pixar’s heft should make a film like WALL•E. Luxuriously in the black on every film they’ve ever made, they have many delighted shareholders and a new boss to keep happy now that they’re officially part of the Disney empire, and a trusting audience whose largest complaint to date has been that some of their films have failed to be instantly classic and merely managed to be very, very good. In the animation world they’re unparalleled in witty dialogue and nice shiny textures, and everyone would probably be happy to devour more of the same for years to come. Well, thank goodness that Pixar appears to have lost some of its business sense, and made a film that’s like nothing we’d expect, except in its quality.

To any other animation studio - and this is why Pixar can make a fair claim to being the greatest in cinema history - WALL•E would not make sense as a mass-market movie. It’s an idea that can only have come from passion and inspiration, not focus groups and marketing meetings. Here we have a robot with a vocabulary that never stretches beyond three words (and all of those are pronounced with an android lisp); a best friend who’s a mute cockroach (ick!), and an obsession with a VHS of Hello, Dolly! (what’s Hello, Dolly! grandad? And who’s VHS?). On top of that, he brings a message about being nice to our planet and the evils of big corporations. He would typically belong, at best, as a secondary character, to fall over or pop a wingnut when the plot looks like getting too romantic.

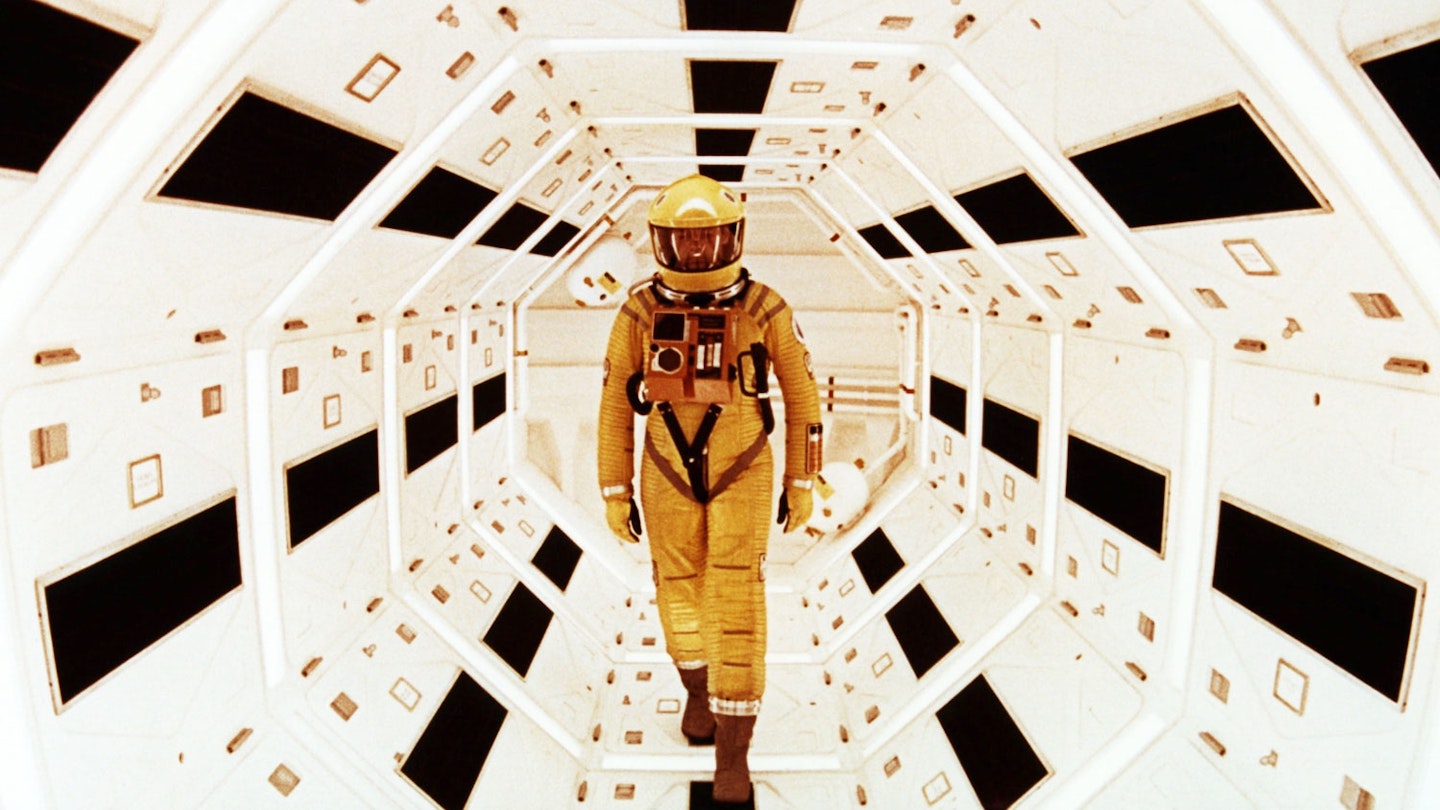

Andrew Stanton, who with Finding Nemo proved himself a fine director of Pixar’s traditional mismatched-buddy movie with a twist, has taken these elements and combined them with amazing elegance into a film of faultless grace, breathtaking sweep and more adorability than a basket of baby bunnies. He opens with supreme confidence on a future Earth composed of dust piles and great skyscrapers of trash reaching toward a permanently overcast sky. It’s a gorgeously nihilistic backdrop that could easily have come from the mind of Ridley Scott or Stanley Kubrick (whose 2001 is playfully referenced throughout), and the most beautiful scenery Pixar has created. You wouldn’t want to live next to it, but it’s awfully nice to look at. Dotted about this wasteland are signs for Buy N Large, a corporation that, we can deduce, has become the supplier of every product on the planet and swiftly scarpered with the population once the rubbish started piling up. The task of clearing up has been left to our hero, a cute little collection of manky hinges and half a Tonka truck. In a rather dark aside, we see a number of ‘dead’ WALL•E’s flopped around the landscape. He is the last.

WALL•E scoots happily around the dilapidated planet to the musical stylings of Michael Crawford in the aforementioned Hello, Dolly!, crushing the detritus of humanity into little cubes. He does his job quietly and diligently and, once the work is done, indulges his obsession with man’s trash: one man’s garbage is another robot’s treasure. Wall•E is a character of genius, as pure and wondrous an example of the possibilities of animation as you will ever see. He’s an encapsulation of all the medium’s ability to give anything personality. He has no eyebrows, mouth, language, thumbs, or any of the humanistic elements that a cartoon generally requires to mimic emotion. Yet everything this little fella feels is perfectly palpable and genuine.

It’s in the smallest tilt of one of his lamp-like eyes, the Chaplinesque nervousness of his gesticulation, the emotive sound design of Ben Burtt (the man who gave R2-D2 his wibbles and beeps, and whose contribution here cannot be overstated). He doesn’t look like much, but his possibilities are endless.

Clearly proud of his creation, Stanton spends an almost show-offy amount of time exploring what it can do. The animators flex their slapstick muscles as our robot friend investigates the possibilities of a fire extinguisher and frets over whether his newfound spork belongs with his spoon or fork collection. The scenes of WALL•E simply existing are the film’s most amusing.

When WALL•E meets EVE, a scout for faraway humanity who looks like a suppository as designed by Apple, the movie transforms. It turns into Annie Hall with robots – Animatronic Hall, if you will. Schlubby, neurotic little WALL•E tries to get up the courage to speak to the more sophisticated girl, often finding his attempts to impress backfiring painfully. If it’s possible for two inorganic objects created inside a computer to have chemistry, then these two have it in spades. A montage of WALL•E trying to rouse EVE from her stand-by mode, and the pair later cavorting through space, are as romantic as anything ever achieved with fleshier cast members. It’s a good thing there’s almost no dialogue, because you’d miss most of it for the sound of the audience ‘ooh-ing’ and ‘aah-ing’.

The story’s departure from Earth onto the ship inhabited by the dregs of mankind is almost a shame, initially. The character work on the two robots is so strong that further embellishment seems unnecessary. It’s at this point that the film has the very slightest of stumbles, with WALL•E briefly becoming lost in the mix as we’re guided around the sterile realm that’s become home to the remaining humans, who are now so used to having their every need catered for that they’ve become giant, swollen toddlers with little stubby legs and an unwillingness to chew, helpless outside their buggy-like chairs. The suggestion is that we’re not far off this and need to take responsibility for our existence (the irony that this message comes from Disney, a company whose bread-and-butter is putting children in front of screens, should not go unacknowledged). The human characters, oddly, don’t have anywhere near the humanity of the robots, and it’s not until focus shifts back to the machines that the movie finds its feet again. It doesn’t sag once through a wacky ending that has shades of Toy Story in its bringing together of a motley band of faulty robots to save the day, and keeps momentum all the way to the end of a credits sequence that is unashamedly preening on the part of the animators, but impossible not to delight in.

That WALL•E is such a triumph sets a new precedent for Pixar. If they are to stick their necks out with a film that veers from their comfort zone and pays great dividends - assuming it’s the hit it deserves to be at the box office - then we as an audience have a right to expect them to continue pushing themselves and taking risks. This experiment is an unqualified success, and means that a simple buddy comedy, even one as intelligently and expertly crafted as Ratatouille, might seem unambitious as a follow-up. We’ll now expect surprise as well as delight. You’ve raised the bar, Pixar: now jump it again.

.jpg?ar=16%3A9&fit=crop&crop=top&auto=format&w=1440&q=80)