In January 1994, Tonya Harding ceased to be famous for figure skating and became infamous following an attack on her skating rival, Nancy Kerrigan. A media frenzy erupted, continuing throughout that year’s Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, where both women competed, before the disgraced skater was banned from major competition for good. But Craig Gillespie’s nuanced and bleakly funny I, Tonya reminds us, while it’s unclear how much or little she knew about it (she eventually pleaded guilty to conspiring to hinder prosecution), Harding did not personally attack her rival, and her reputation as a brawling skate monster is deeply unfair.

We meet Harding as a child (played by Gifted’s Mckenna Grace), pushed into skating by her overbearing mother LaVona Fay Golden (Allison Janney). Golden insists on her daughter’s talent, browbeating local coach Diane Rawlinson (Julianne Nicholson) into taking her on. But motivating her daughter involves cruel taunts and the neglect of any of Harding’s needs beyond skating — even taking her out of school so she’ll be dependent on her mother’s support. Harding becomes a formidable competitor, but it leaves her isolated, a state of affairs that Golden seems to both cultivate and resent. The relationship we’re shown is physically and emotionally abusive, played out against a background of hard-scrabble poverty that’s a world away from the usual figure-skating ice princesses.

As a teenager, Harding — now Robbie — escapes into the arms of mechanic Jeff Gillooly (Sebastian Stan). He’s the epitome of ’80s cool — all anoraks and Freddie Mercury moustache — but their on-off relationship is also abusive, with Harding dodging his fists between practices. Meanwhile, her talent is undeniable, but her star rises slowly, held back by judges more fixated on her dishevelled appearance than on her ability to land a triple axel with double toe loop. The class commentary is clear: if Harding had come from a wealthier background, she wouldn’t have been shunned by the skating community — nor so pilloried for someone else’s actions.

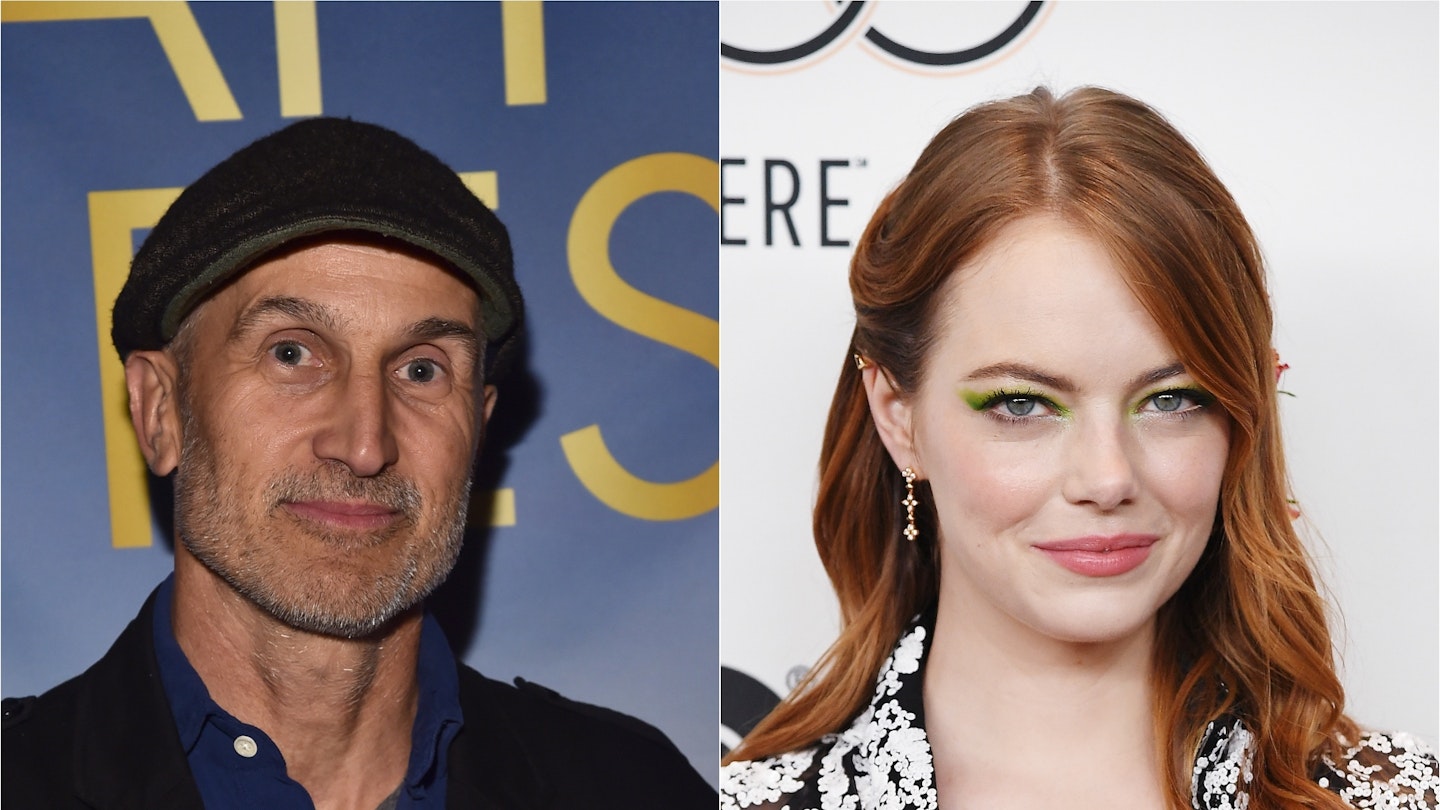

Margot Robbie gives a vanity-free performance under a series of horror wigs.

Robbie impresses as a woman who wasn’t initially given a choice about skating but who absorbed her mother’s resolve to win along the way. It’s a vanity-free performance under a series of horror wigs, capped by a desperate grin more disturbing than the one she wore as Harley Quinn. This Harding is more sinned against than sinning, but was still prone to outbursts of rage and terrible life choices — so she’s no bland heroine.

Yet Robbie’s more than matched by Janney, uncompromising as she claims to have acted out of love. Golden is flamboyant, with her fur coat, a bird on her shoulder and an oxygen line snaking across her face after a lifetime of smoking, but also small, sad and bitter after her predictions of disaster come true. Even by Janney’s standards it’s an unforgettable performance (deservedly awarded a Golden Globe). And Stan, usually relegated to winsomely damaged roles, does an impressive face-heel turn when he morphs from Harding’s saviour into her nemesis.

If there’s a criticism, it’s that the film sometimes gets distracted from getting under Harding’s skin by stylistic flourishes and its fascination with the weird world of her unbelievable life. Gillespie adopts a free-wheeling, unreliable-narrator-led approach framed by contradictory interviews with an older Harding, Golden and Gillooly, mining humour from their disagreements. Add the quick cuts, bright colours and pumping soundtrack, and you can see why this has been compared to GoodFellas. But it’s a consciously less stylised film, shot under ugly fluorescents and in a bleached-out gold that matches Robbie’s frizzy perm. There’s also shakiness in some CG efforts to transpose Robbie’s face onto the skating double.

Still, it’s consistently gripping — a tale that assumes the audience’s complicity in Harding’s trial by media, then forcing us to reconsider. Harding was a victim who refused to act like it, putting up an ultra-tough front for the world. So we made her a villain instead, and never mind the human consequence. Until now, anyway.