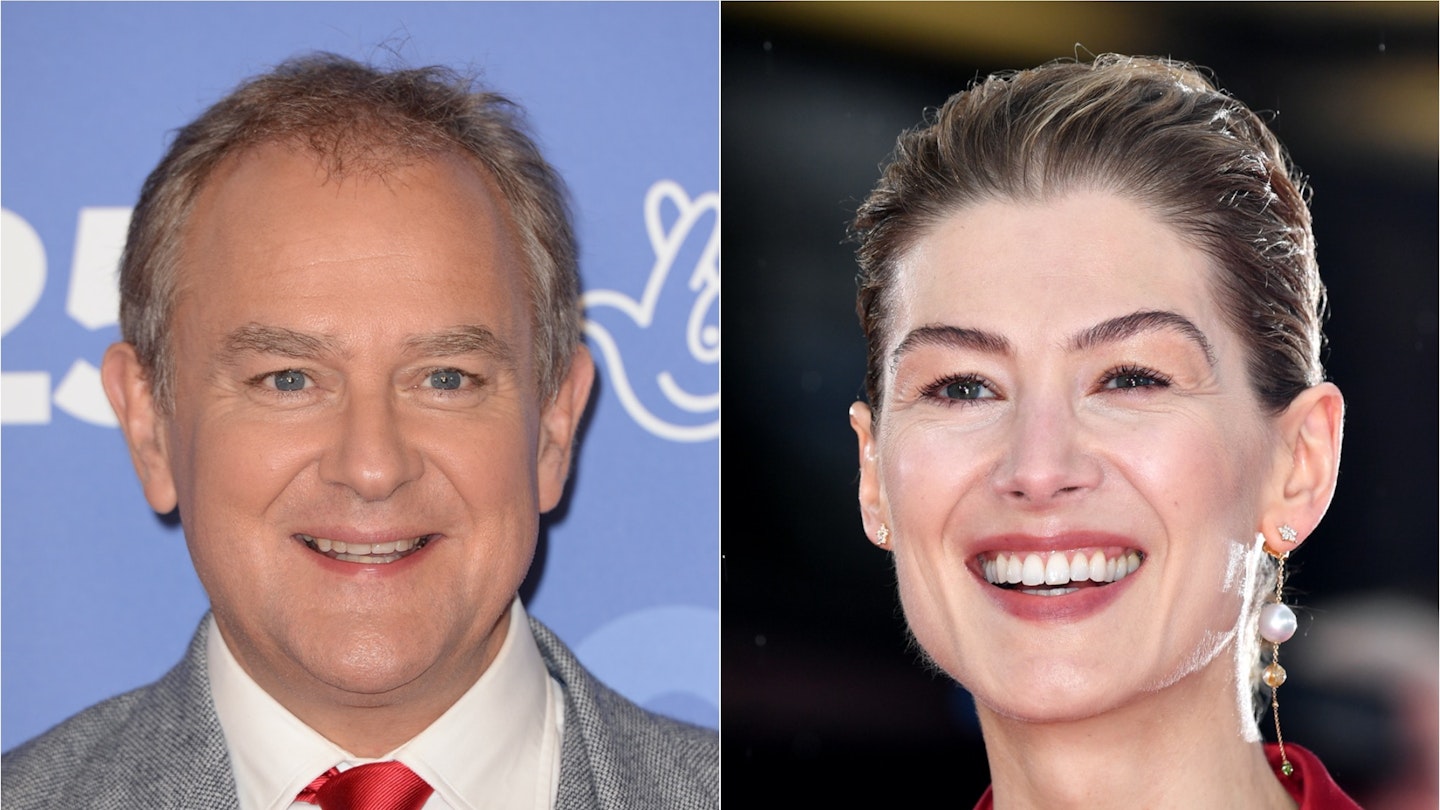

The lives of British authors, especially children’s authors, seem to be catnip to filmmakers. A.A. Milne, J.M. Barrie, Beatrix Potter, C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien and the Australian-British P.L. Travers have all had their stories dramatised. Now Hugh Bonneville dons a distracting prosthetic nose to play Roald Dahl in a story that touches on his literary efforts but focuses primarily on his marriage to actor Patricia Neal (Keeley Hawes) as they endure an unspeakable family tragedy. If it’s not as schmaltzy as a few of its predecessors, nor does it offer much fresh insight into the Dahls’ lives.

with a first-base script and a reliance on overly familiar beats, this sometimes skims the surface of its characters’ lives.

We open at a moment when both parties in the over-achieving marriage were at a low ebb. Dahl’s James And The Giant Peach was struggling to find a readership and Neal’s early successes were a decade and three children behind her. With the bills mounting, the mildly squabbling couple take comfort in their family — until the sudden death of daughter Olivia (Darcey Ewart) destroys their equilibrium.

The Dahls seek solace from faith — the great Geoffrey Palmers appears, in his last film role, as the Archbishop of Canterbury — and in denial, Dahl throws himself into work, a new book about a chocolate factory, while Neal contemplates a return to the screen for a juicy new role in Hud. It’s a tragic fact that, as they coped with Olivia’s loss, both partners would experience extraordinary career breakthroughs. But the film doesn’t quite get around to exploring what must have felt like bitter and inadequate compensation from the universe, framing this instead as a largely feel-good tale of triumph against the odds.

That’s unfortunately a general problem for co-writer and director John Hay’s work here: with a first-base script and a reliance on overly familiar beats (the parent packing up the child’s room, the metaphor involving birds), this sometimes skims the surface of its characters’ lives. But the moments that do connect — largely involving Olivia herself — are undeniably moving.