It was certainly a brave undertaking, tackling what is not only one of the greatest espionage novels ever, but one whose 1979 serialisation by the BBC lingers in the memory of everyone of a certain age. It’s a pleasure and a relief, then, that the film succeeds in its own right. It is a superior whodunnit thriller and a very grown-up one, devoted not to guns, girls, gadgets and glamour, but to the little grey cells. And in plumbing George Smiley’s grey matter, Gary Oldman has understood the illusion of being a nondescript sort of little man with a remarkable mind, authority and a gut full of secret sorrows and sins behind the serious spectacles.

The starting point is a fine screenplay by Peter Straughan and the late Bridget O’Connor that rings a few changes to John le Carré’s tale. Most of them are subtle, sensible, and a couple are even a touch humorous. It probably goes without saying that the sterling cast is uniformly on top of things, undoubtedly delighted to find themselves in such excellent company. The real stroke was recruiting Tomas Alfredson. With Swedish melancholia in vogue, the Let The Right One In director proves an ideal choice to turn a baleful gaze on le Carré’s perfectly miserable spies — a breed of men he characterised as unromantic figures prone to unpleasant stomach ailments and trouble with their wives. Alfredson is clearly a kindred spirit of both le Carré and Smiley, intently focused and with a dispassionate eye for the small, telling detail: on a face, in a room, from a conversation.

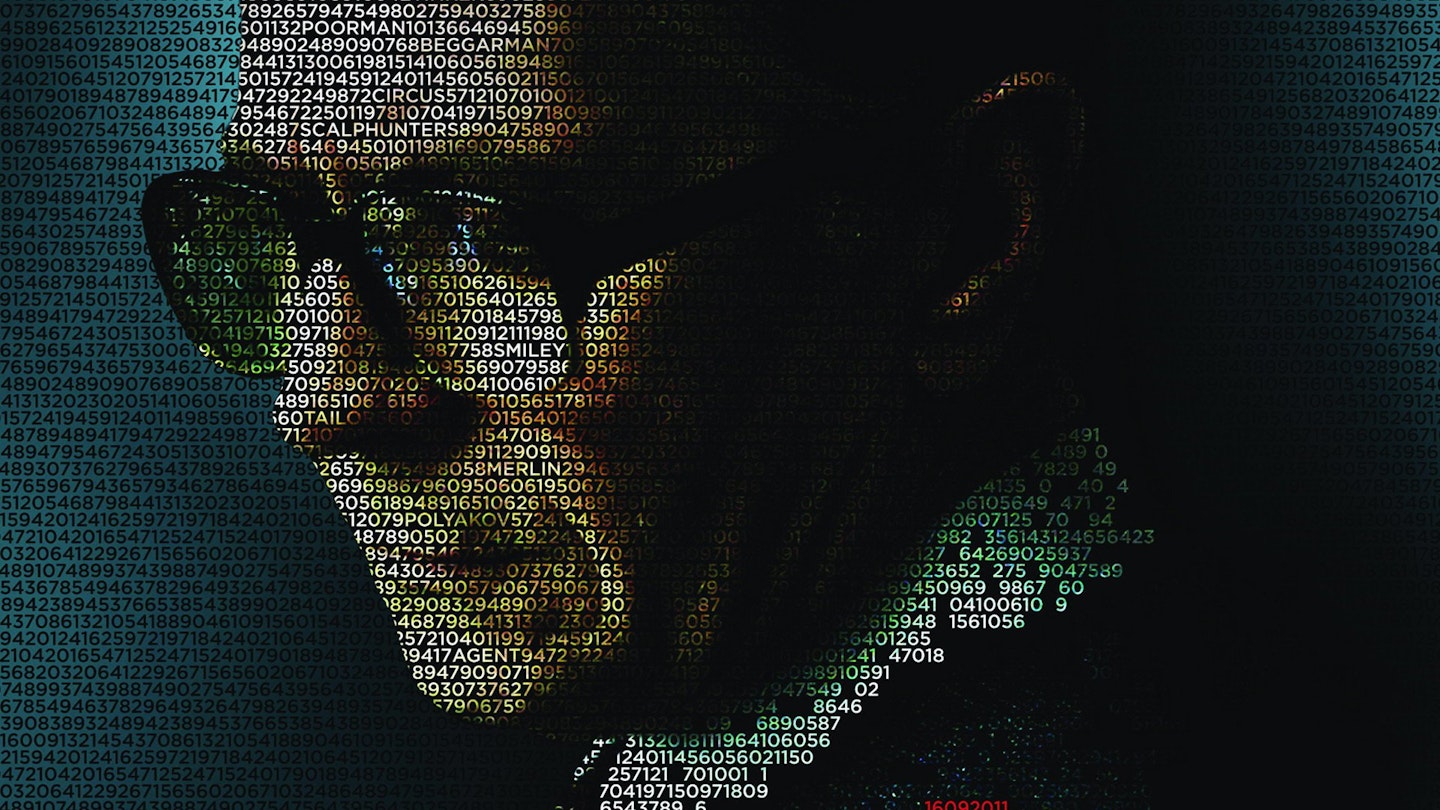

Pulled back into the Cold War spy game to unmask the traitor in the Circus that is MI6, Smiley learns that Control (John Hurt) had sniffed the mole and assigned code names for his principle suspects. Tinker is smug Percy Alleline (Toby Jones). Tailor is sardonic Bill Haydon (Colin Firth). Soldier is bluff proletarian Roy Bland (Ciarán Hinds). Poor Man is prissy émigré Toby Esterhase (David Dencik), and sadsack Smiley, also a suspect, Beggarman. Evidently Control grasps Smiley’s two weaknesses: his love for faithless wife Ann, and his fascination with Soviet counterpart Karla. It’s a great decision that we never see the faces of Ann or Karla, shadowy figures who loom large in Smiley’s capacious memory. In one particularly arresting scene, Smiley relates his sole face-to-face encounter with Karla years earlier — not through flashback, but an anecdote in which he becomes uniquely animated, re-enacting his dialogue with the cruelly astute Russian.

Other key players in the chess game include Mark Strong’s dutiful, tragic Jim Prideaux, dangled as bait, betrayed and abandoned… to become a teacher. Nowadays, of course, it is hard to imagine even the most third-rate public school engaging a darkly mysterious man with no past and permitting him to entertain small boys to tea in his rackety-packety caravan, but it’s in keeping with the seediness that deliberately pervades the whole shebang, from the desiccated Control, with his messy rooms and his paranoid plotting, to the nicely cheesy selection of Julio Iglesias warbling La Mer over the end montage.

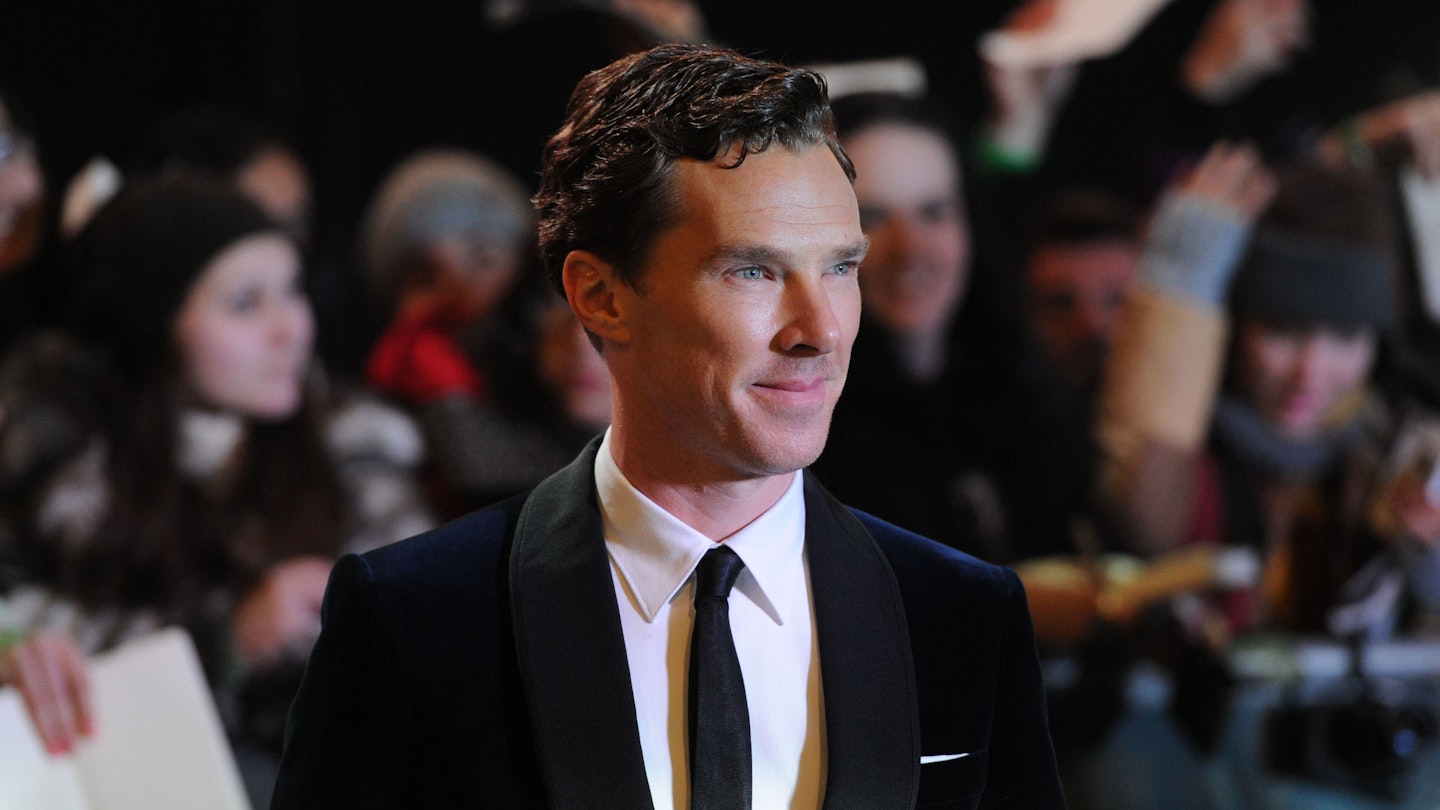

It’s probable Benedict Cumberbatch had the most fun as Peter Guillam, Smiley’s trusted legman (amusingly, TV’s Sherlock plays what Ian Nathan aptly described as Smiley’s Watson) with a groovy narrow-cut suit, fruity ties and a ’60s pop-star haircut. He features in a showpiece nail-biter of a sequence; it’s the good old filching-of-secret-documents routine, but his progress from the security entrance and through the corridors of The Circus — brushing by suspects and the suspicious — is achieved with sweat trickling in suspense. Tom Hardy is the bit of rough Ricki Tarr, a foot soldier at the thuggish end of field work, but one with the instincts to know when he’s been sent on a fool’s errand and when to run. It is the return of AWOL agent Ricki that raises the alarm and sets Smiley on the right track. It’s wonderful to see Kathy Burke cajoled back into acting for a key scene as boozy Connie, the researcher forcibly retired to shut her up and shelve her encyclopedic memory. There’s even a cameo from le Carré, who can be seen among the Circus staff drunkenly hailing the arrival of Santa Lenin at the ghastly office Christmas party revisited in a series of discreetly revelatory flashbacks.

Those who have not read the book or seen the BBC version do not need to worry overmuch about plot complexities or following the threads — Ricky Tarr’s odyssey out in the cold, the workings of Alleline’s pet project Operation Witchcraft, the language of the ‘service’ — although they are well laid out. What matters are the layers and levels of betrayal, to country, cause, colleagues, lovers and to self, from great to small, like a nested Russian doll.

Rarely do critics complain that a film isn’t long enough, but this is the almost freakish exception. The film is so well paced over its two-odd hours, but another half-hour could have been used to give the suspects more to do and to generate yet more suspense and concern about which of them is the traitor. It’s really the revelation of the mole that lets the side down — it doesn’t deliver the punch to the gut one wants. Of course, if you haven’t worked out who it is by then, you must be very innocent in the ways of these things. Of course it is him. It had to be him. But his all-of-a-sudden apprehension and the tableau greeting the latecomer arriving at the scene of the double-dealer’s downfall, while laudable in its restraint and lack of histrionics, is a trifle too cool.

Oldman’s performance is most eloquent and expressive in his fluent command of body language. The set of his shoulders and his posture, the occasional adjustment of his spectacles, tell you precisely what’s going on in Smiley’s mind. There is a moment near the end when we only see him from the back but feel an electric thrill, knowing with certainty by his stance that his heart has leapt at what he has seen. Alfredson is startlingly adept at envisioning how Smiley’s mind works; you can almost see the wheels turning as the pieces of the puzzle click together (at one point you literally see tracks converging as he nears his ‘Eureka!’ moment), and a clever piece of sound editing filters conversations through Smiley’s thought process until he homes in on a phrase that is the key to everything. And then there is his face in his final shot; we recognise the sweet taste of game over, game well-played in his mouth.