Todd Haynes is perhaps the perfect filmmaker to document the short life and weird AF times of The Velvet Underground. Not only are Haynes’ music dramas Velvet Goldmine and I’m Not There set in the same era as Lou Reed’s band operated in, but the filmmaker and group are united in sensibility: marginalised artists constantly pushing the envelope in challenging ways. With many of the major players no longer with us, Haynes still creates an ambitious, immersive portrait of one of music’s most influential, maverick acts. What it lacks in critical edge, it makes up for in imagination and a sense of the bigger picture.

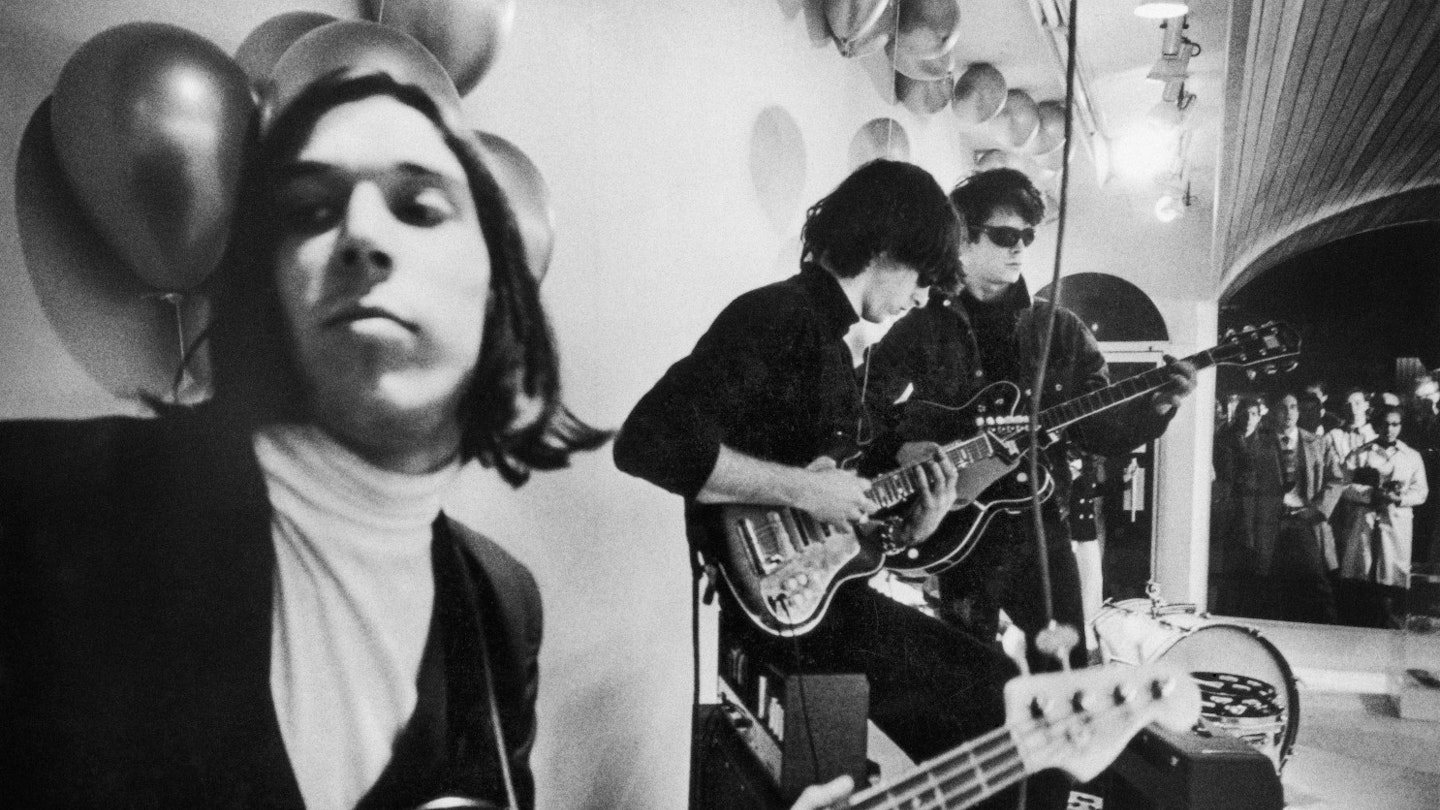

Given Haynes’ experimental CV, the structure of The Velvet Underground cleaves surprisingly closely to rock-doc conventions (how they met, the success, the dis-banding). Yet Haynes’ M.O. is anything but straightforward. Taking his cue (and footage) from the avant-garde filmmakers of the ’60s, Haynes employs an almost ever-present use of split-screen — De Palma would be green with envy — juxtaposing interview material with adverts, newsreel, photographs and footage of the band made possible by the continuous presence of a camera documenting things at The Factory, Andy Warhol’s creative hothouse (the archival research is immense). As much as the film is a portrait of a band, it also crystalises the whole ’60s scene: The Velvet Underground not only documents the period but also feels like it could have come from it.

Within the impressionistic approach, the biographical beats are clear, Haynes deep-diving into the different backgrounds of founding members Lou Reed and John Cale without baulking from the darkness. Reed came from a stultifying suburban background — suffering clinical depression as a child, undergoing electroconvulsive therapy (which his sister denies was to curb his homosexual tendencies) and developing degrading views of sex. Cale was raised in a Welsh mining village, wasn’t allowed to speak English until aged seven and was molested by Anglican priests. The odd couple — Reed wanted to be a rock star; Cale an experimentalist — came together in a Lower East Side loft (where else?), and Reed’s song-writing became informed with Cale’s improvisational genius, the music described as “the drone of Western civilisation”.

When the action moves onto Andy Warhol and The Factory, Haynes really puts you in the room. It’s here that German guest vocalist Nico enters the picture — much to Reed’s annoyance — shines brightly, then leaves. Reed’s all-round fractiousness — he once punched his hand through a glass door to get out of a gig on a river boat — gives the film its juice; as far as Haynes' film is concerned, once he fires Cale it marks the beginning of the end.

Haynes doesn’t spend a lot of time analysing the music — Jonathan Richman of the Modern Lovers dissects their stripped-back recording processes — and there’s little in the way of dissenting voices. As such, The Velvet Underground works best as a time capsule and in terms of offering a sense of artists as rebels. Haynes has made a career out of celebrating fictional outsiders. It’s perhaps no surprise he does just as well with the real thing.