If this were 2015, there is a very good chance that The Vast Of Night would have landed first-time feature director Andrew Patterson a Jurassic off-shoot, a Star Wars anthology film or at least a high-profile Super Bowl commercial. Told with assurance, style and grace, Patterson’s low-budget marvel — it was paid for by money the filmmaker made from commercials — mashes up sci-fi paranoia, the beginnings of TV, teen character studies and the golden age of radio into a seamless, completely cinematic cocktail. It acts simultaneously as a brazen calling card yet is also controlled, mature, and in its final moments strangely melancholic and moving.

James Montague and Craig W. Sanger’s screenplay starts boldly, opening on a TV showing a Twilight Zone-ish show, ‘Paradox Theater’ (“You are entering a realm between clandestine and forgotten. Tonight’s episode: ‘The Vast Of Night’”). Set in a small New Mexico town, Cayuga, on the night of a big high-school basketball game, we zero in on the only two kids not interested in the hoops action. Working the graveyard shift on the town’s switchboard while simultaneously listening to WOTW disc jockey Everett (Jake Horowitz), electronics nerd Fay (Sierra McCormick) takes a call from a woman who tells her that three large objects are hovering above her house, before the phone disconnects. At the same time the WOTW signal starts getting interrupted by bursts of garbled audio transmissions, faint, disembodied voices in a sea of static (Everett suggests it’s those pesky Russkies). When Fay picks up the same static, patches it through to the radio station and Everett puts it live on air, the listener reaction sends the pair on a chase around Cayuga to discover what is going on.

On a microbudget, Patterson and crew effortlessly evoke the ’50s, but with a clear-eyed lack of kitsch or nostalgia.

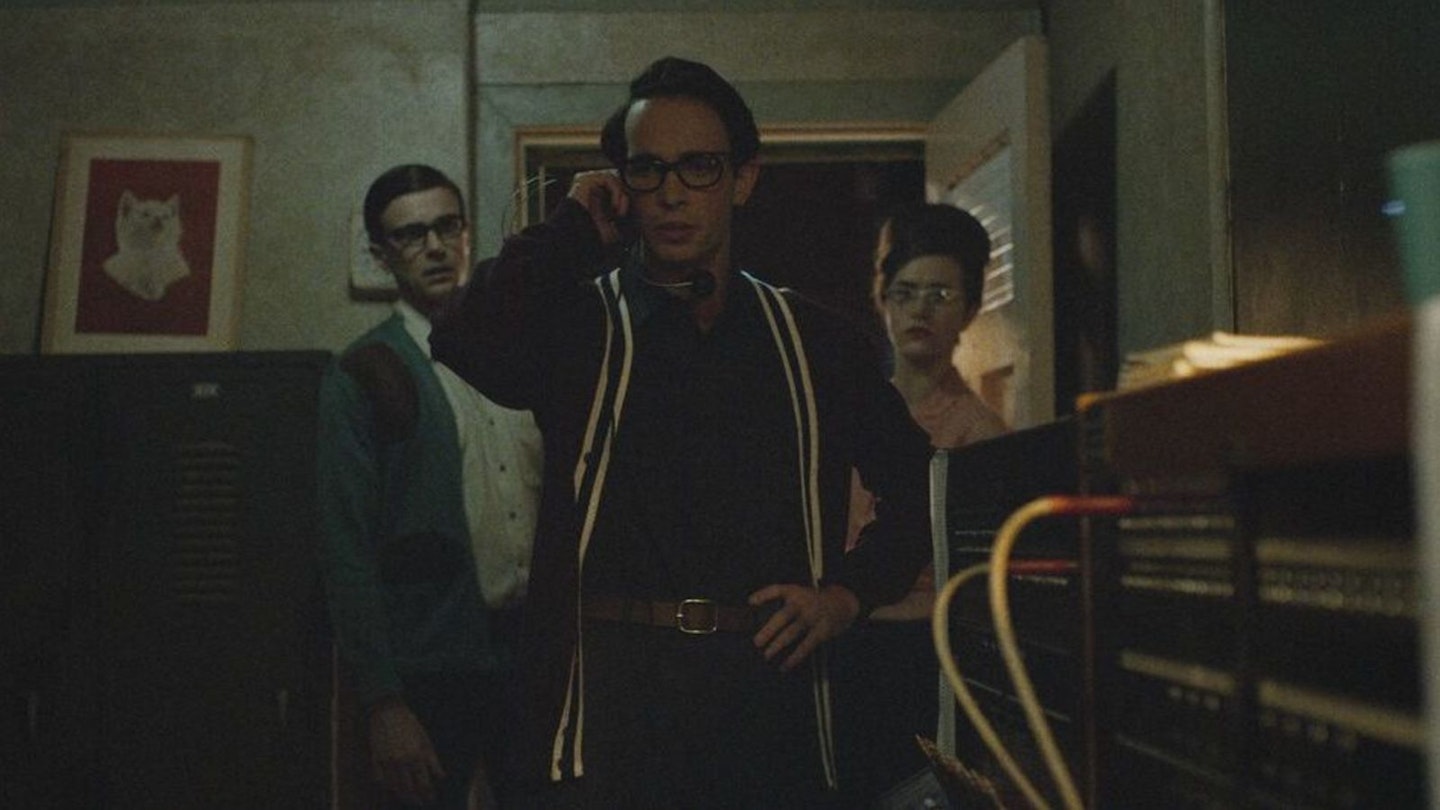

Patterson brings out every trick in the book to make his story, often told through long conversations, eerie and compelling. At one point, as Fay works the switchboard, M. I. Littin-Menz’s camera stays on McCormick’s face and lets the drama play out in her eyes, framed by horn-rimmed glasses. At other times, the camera fluidly moves across landscapes strewn with ’50s Americana, including a jaw-dropping oner that starts on a street, crosses a parking lot and travels through a basketball game, before plunging through a window. On a microbudget, Patterson and crew effortlessly evoke the ’50s, but with a clear-eyed lack of kitsch or nostalgia. You believe every minute of it.

It might be too talky and obscure for some tastes, but there’s good chemistry between the two leads (McCormick is the break-out), and the film passes subtle notes from America’s nuclear age to today: without ever hitting you over the head with it, the callers to the radio station are from side-lined groups— Black people, women — gently reminding us to heed marginalised voices. After all the chat, the film delivers on spectacle but admirably goes for something different from Spielbergian wonder. It’s another original note in a film that has a Donnie Darko frisson about it: small, personal, perfectly formed sci-fi weirdness that comes off a treat.