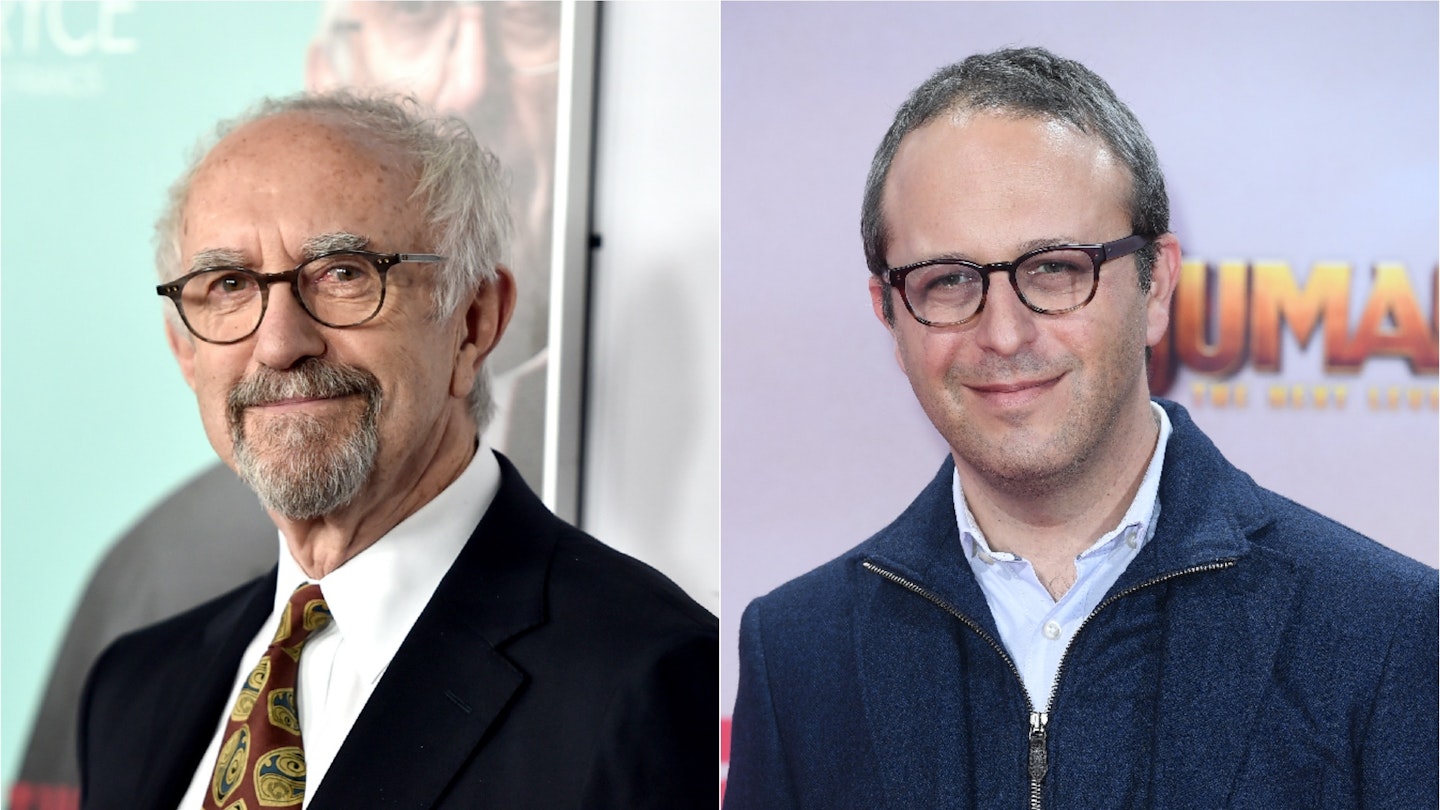

The Two Popes is far more entertaining than a film about the internal machinations of the Catholic Church has any right to be. Playing out a battle of wits between Pope Benedict XVI (Anthony Hopkins) and Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio (Jonathan Pryce), Fernando Meirelles’ film deftly pulls off the knotty challenge of dealing lightly with complex dynamics and weighty themes, all delivered by pitch-perfect performances from two veteran British thesps. Funny, engrossing and thoughtful, the result is Meirelles’ most entertaining and watchable film since City Of God.

Following a funny opener in which Cardinal Bergoglio tries and stumbles to book a flight over the phone, the film segues to 2005, as the world learns of the death of Pope John Paul II. It’s typical of Meirelles’ brio that he plays Abba’s ‘Dancing Qeeen’ (a Bergoglio fave) over the procession of Cardinals getting ready to vote for the new Pontiff. What follows is a fascinating almost documentary-like recreation detailing the process a Pope gets elected — close-ups of pens clicking, black balls swirling, the creation of black smoke when there is not a unanimous decision — until a decision about the new bishop of Rome is finally made: the dyed-in-the-wool traditionalist German Cardinal Ratzinger (Hopkins). In a surprising second place is the radical reformist Bergoglio. We see the two men meet briefly — their cursory handshake redefines cursory.

Meirelles takes a two-handed chamber piece and makes it fly.

It’s now we learn Bergoglio’s reason for booking that flight: he has booked his flight to resign to Ratzinger and resume his role as a parish priest. Yet simultaneously Ratzinger has summoned Bergoglio to his summer retreat at Castel Gandolfo. At this point screenwriter Anthony McCarten, elevating his level here from The Darkest Hour and Bohemian Rhapsody, comes into his own, creating gripping scenes of Ratzinger refusing Bergolio’s resignation and sizing him up for another purpose: to see if he is a suitable candidate to take over as Pope. With the Catholic clergy embroiled in sex scandals (the film would make an interesting if intense double bill with François Ozon’s For The Love Of God), Ratzinger knows the Church needs to evolve: can he persuade the resigning Bergoglio to take over?

But if this sound like 128 minutes of ecclesiastical debate and doctrine, it isn’t. McCarten’s writing has the two men carefully circling each other, their battle of wits flitting between tension, high-mindedness and irreverence as the pair work through their differences — the real skill here is that buried within the sparkling dialogue is a monumental shift of power that rocks an institution. He also doesn’t forget to include touches of humanity, making very clear distinctions between the two men. Ratzinger has a penchant for Austrian cop-dog series Kommissar Rex (a German Shepherd who solves crimes) and recalls his former career as a singer turning down the chance to sing at Abbey Road. Bergoglio has an altogether darker backstory, his refusal to take a stand against Argentina’s military junta in the 1970s relayed in striking black and white with Juan Minujin registering strongly as the younger Bergoglio. If occasionally confusing, these sections completely inform Bergolio’s hesitancy to commit to the papacy.

With all the talk of what constitutes cinema recently, Meirelles takes a two-handed chamber piece and makes it fly. Early scenes in Argentina recall to mind the energy of City Of God but he also knows how to stage scenes in eloquent close-ups or, as in a helicopter journey, play with sound to dramatic effect. He has a sense of fun — listen out for the chintzy Italian travelogue music as Bergoglio arrives in Rome — and a sense of scale (a telling top shot of the two Popes in a maze, a key conversation takes place against a stunning recreation of the Sistine Chapel in Cinecittà Studios). But The Two Popes is a film that lives and dies on its central performances and in Hopkins and Pryce’s hands, it thrives. While Hopkins runs the gamut from ferocious to fragile but always with a twinkle in his eye, Pryce is charisma personified but masking a deep seam of sadness. They are the reason the relationship between Ratzinger and Bergoglio crackles, their chemistry shining in a stay-in-your-seat end-credits footie related coda. It’s the miracle of the movie in a nutshell.