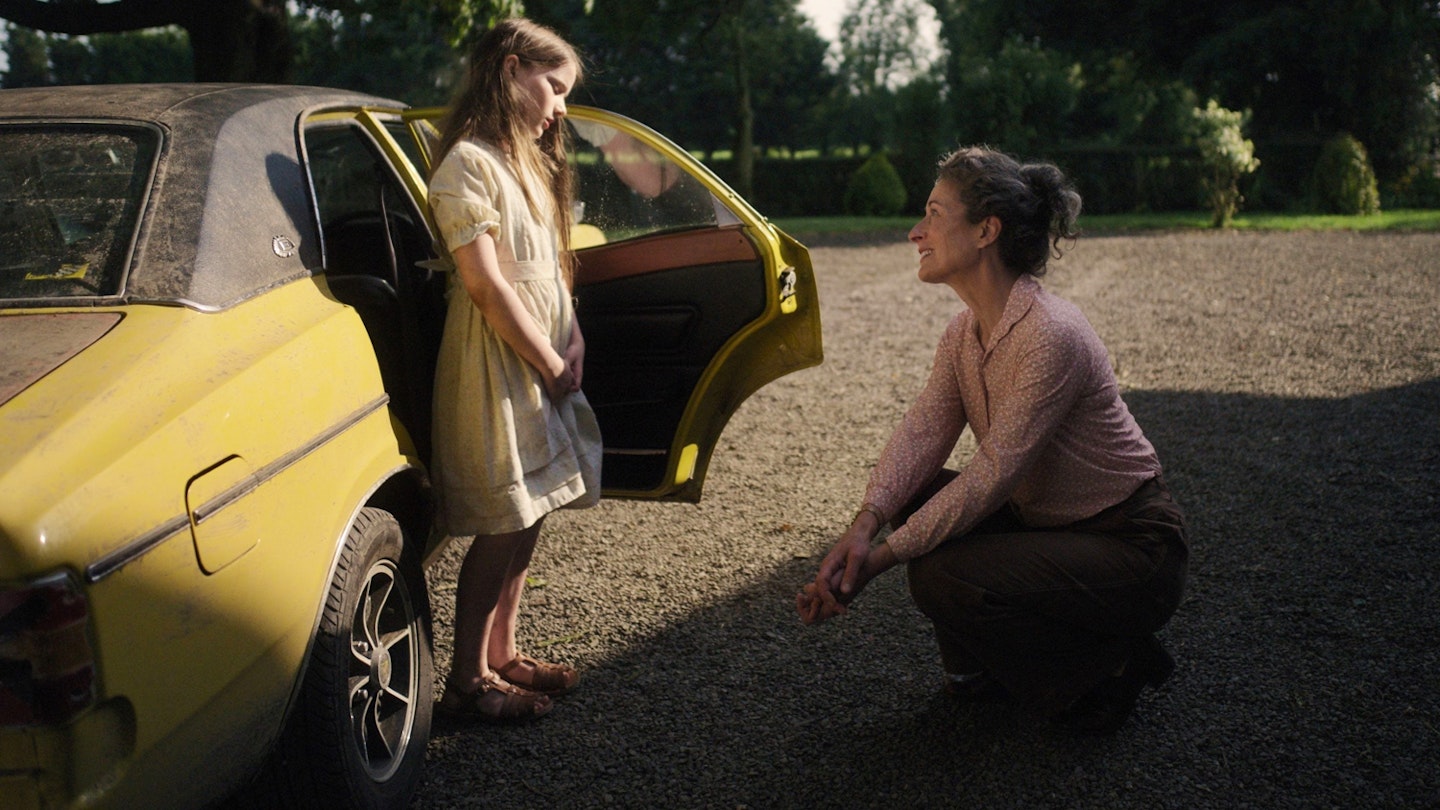

The Quiet Girl is, not unexpectedly, a quiet film. With dialogue almost entirely in Irish, a language still woefully underrepresented on screen, the film follows Cáit, played by newcomer Catherine Clinch with a tiny whisper of a voice and hugely impressive understatement. She’s a shy, sad schoolgirl in an unhappy family, sent away to spend the summer with her mother’s cousin; there, she’s shown a simple, uncomplicated tenderness, forging a family of the kind she’s clearly never experienced before. It’s a simple but artfully effective debut feature from Irish filmmaker Colm Bairéad, with a remarkable, heartbreaking debut performance from Clinch, whose face betrays anxieties she doesn’t yet fully understand.

The film is low on incident, but generous to its characters and invigoratingly sweet.

The dialogue, when it comes, is gentle and lyrical. Bairéad’s screenplay (adapting a novella by Irish writer Claire Keegan) finds poetry in the shapes and contours of his native tongue, and even if you’re not an Irish speaker, you’ll find beauty in the language. It’s an obvious comfort to Cáit, too; tellingly, the few English speakers in the film are characters she fears or struggles to trust, such as her belligerent, emotionally inert father (Michael Patric), who only has time for talk of weather or gambling.

The title nods to the quietness of its title character, but in truth, this is a film full of people unable to express themselves, inner turmoil in different forms. Cáit’s parents are sad and unfulfilled; Cáit herself struggles to make friends; and her foster parents, though much more open and loving, have a grief-filled history they are not sharing. It takes acts of mutual care and affection for any lines of communication to open.

With artfully sedate camerawork — the perspective never leaves Cáit’s vantage point — and naturalistic cinematography from director of photography Kate McCullough, Bairéad’s debut film finds a comfort in stillness. A gorgeous minimalist score from Stephen Rennicks (Normal People) augments the effect. The film is low on incident, and could easily threaten to be slight, but it’s generous to its characters and invigoratingly sweet, ultimately singing to the virtues of peacefulness. Sometimes, the film ponders, it’s better not to say anything at all. “She says as much as she needs to say,” Cáit’s adoptive father says of her. “May there be many like her.”