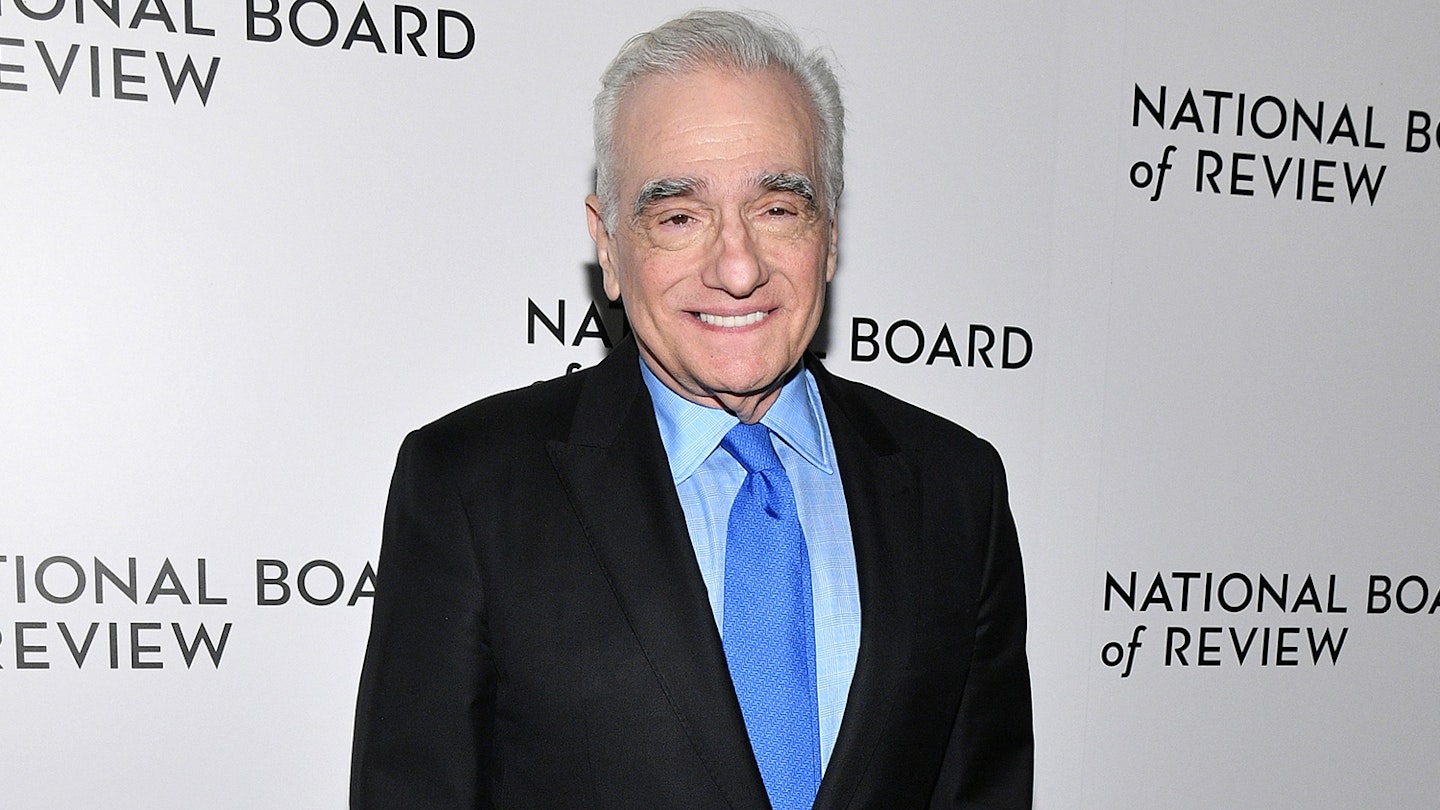

If you know anything about The Irishman, you’ll know two things: CGI ageing technology has made Robert De Niro, Al Pacino and Joe Pesci look like young bucks, and it’s really long (three-and-a-half hours). Well, it’s the genius of Martin Scorsese’s film, based on Charles Brandt’s book about Mob foot soldier Frank Sheeran I Heard You Paint Houses (a euphemism for splattering the walls with blood), that neither really come into play. For Scorsese, helped by terrific performances across the board, replaces curiosity about technical trickery (you get over it so quickly) with fascination with a man’s life. While it delivers all the Scorsese-ness you want (you’ll lose count of how many times someone gets shot in the face), this is Marty in mature mode, a compelling meditation on time, ageing, connections and guilt that reaches the parts other gangster films only dream of.

If you want to see how The Irishman departs from Goodfellas, it’s present and correct in the very first shot. If the latter once saw the camera snaking behind Henry Hill parading his new girl through the Copa, The Irishman opens with a slow deliberate move through a Catholic OAP home, past orderlies and wheel-chaired patients, to land on an ageing Frank Sheeran (De Niro) recounting his story to an off-screen interviewer (a nurse? A priest?). After the serious, spiritually minded Silence, the first hour is Scorsese having fun in the old neighbourhood. A World War II Vet stationed in Italy (this is how he learns to speak Italian and kill people comfortably), Frank meets Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci), the elegant, sinister boss of the Pennsylvania-based Bufalino crime family. The pair hit it off and what follows is vintage Marty. There are scams with steaks, characters talking to camera like a mobster Fleabag, colourful gangster nicknames (Whispers, Sally Bugs, Tony 3 Fingers, Pete The Greek), almost documentary like details into gangster M.O. (Sheeran points a spot in a river where hit men drop their weapons leaving “enough guns to arm a small country”) and oodles of dry, wise-guy wit. We also get glimpses of Sheeran’s homelife. When daughter Peggy (Lucy Gallina) tells him her employer shoved her, Sheeran marches around to the grocery store and gives him an almighty beating. It’s a character trait — a desire to protect his family but with no real idea how — that comes to reverberate in the third act.

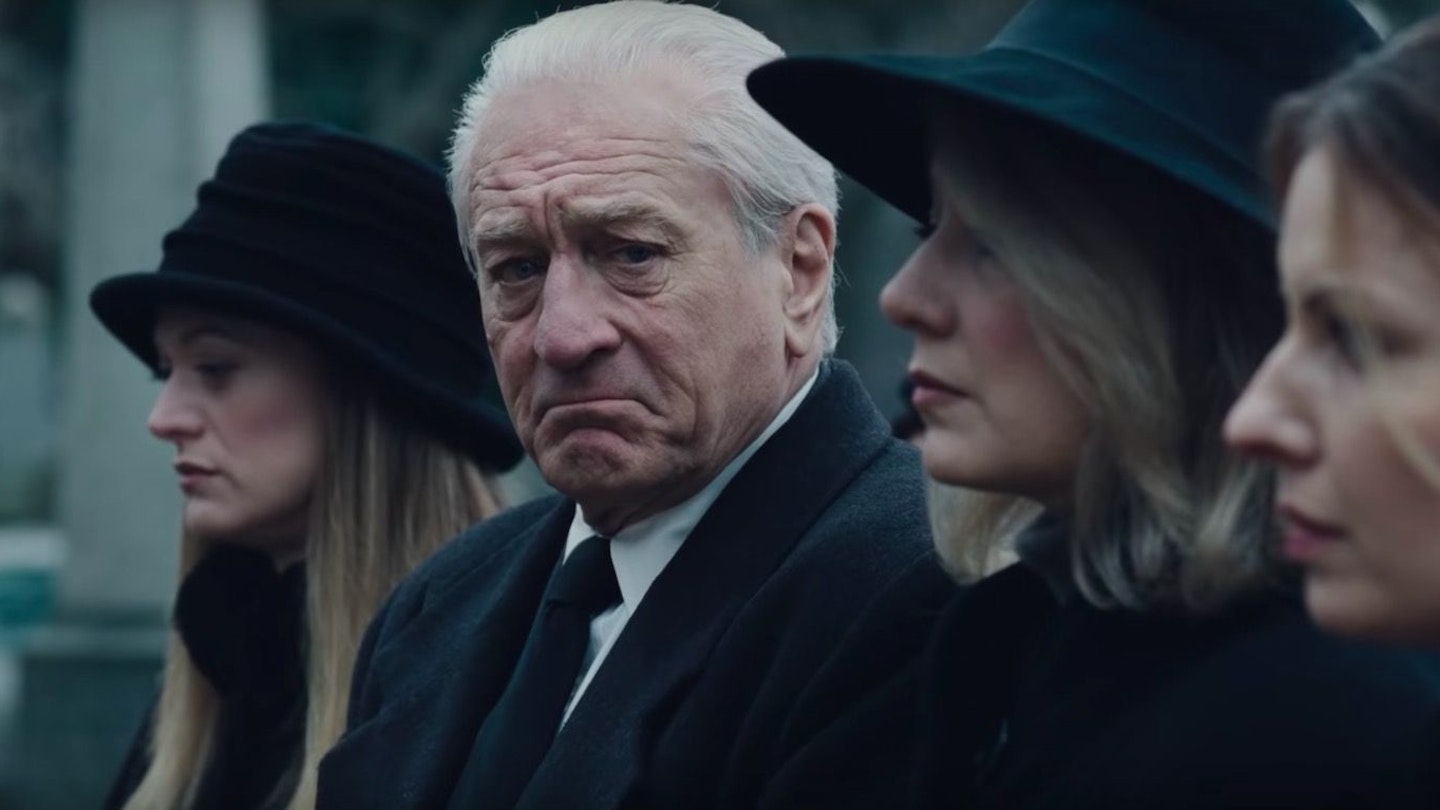

De Niro is equally dialled down, a man at the centre of the action but always removed from it. It’s his best work in years.

Of course, part of the joy of all this is seeing De Niro and Pesci back on their bullshit. Pesci’s Bufalino is a fantastic creation, a polar opposite of the livewires he has previously played for Scorsese. He is a polite non-smoker (there is a running gag about women lighting up in his car) and on the surface likeable, but Pesci imbues him with a quiet, frightening quality. Pesci remains precise and measured. His scenes with De Niro crackle with chemistry but also go off into some unexpected places: a discussion about family — Peggy is terrified of Bufalino and it carries an interesting thread through the movie — at a bowling alley has a tenderness surprising giving the actors and milieu. De Niro is equally dialled down, a man at the centre of the action but always removed from it. It’s his best work in years.

As Frank gains Bufalino’s trust, he rises up the ranks and is given an important assignment: to babysit Jimmy Hoffa (Pacino), the volatile leader of the Mob-sponsored Teamsters union, the second-most powerful man in America and currently under investigation by big business and the government. The Irishman is the first time Scorsese and Pacino have worked together, and they couldn’t have found a better fit. A huge, colourful character, Hoffa lets Pacino organically let rip, the histrionic outbursts that have become part of his acting persona — whatever the role — feel right and just here. Best of all are his run-ins with Stephen Graham’s New Jersey crime boss Tony Pro; one fist-fight which starts over wearing shorts to a meeting and what constitutes being late is one for the ages. There’s a fantastic moment where, on the day JFK is shot, Hoffa sees his union HQ has lowered the stars and stripes to half mast and forces them to raise it. But Hoffa never becomes a clown: he is cunning, a control freak (he doesn’t drink alcohol so his underlings inject booze into watermelon to get their fix) and intelligent, and Pacino plays it to the hilt.

It’s in this middle stretch where the film slightly loses its focus. In his ambition, Scorsese tries to broaden the story into a history lesson, intercutting newsreel footage of the Kennedy and Nixon years, but never really makes the connection between the underworld and politics substantial and satisfying (that feels like another film). The film also misses the spiky female presence of a Lorraine Bracco (GoodFellas) or Sharon Stone (Casino), but Anna Paquin, as a grown-up Peggy, gives it something else, adding another chill to the film’s cold heart with limited screen time.

The film is better when it sticks to the dynamics between the characters and it picks up superbly as the various conflicts come together. But what lifts The Irishman head and shoulders above every other recent crime film is that it doesn’t end when the bodies are buried and the gangsters are locked up. Instead it becomes a powerful, painful study of regret, but not remorse. “You don’t know how fast time goes by ’til you get there,” says Frank towards the end as the film becomes about counting the cost of a life of crime. Sheeran is emotionally unintelligent — a call to a widow trying to express his sympathy is excruciating for him and us — but there is little time in all the ‘painting houses’ to consider and reflect. Scorsese and writer Steve Zaillian give him that epiphany towards the end and its heartbreaking — a man who has killed so many people has also murdered his ability to feel. There is little in the gangster canon (perhaps the end of The Godfather Part II) or Scorsese’s back-catalogue to match the surprise or emotional wallop of the ending. The result is a master working at the top of his game.