Where do you go when you’re lost? If you can, you find a way home. In many ways, this is the path that filmmaker Scott Derrickson has chosen. After exiting Marvel’s Doctor Strange In The Multiverse Of Madness (possibly via a glowing orange portal) during pre-production, having successfully launched the character on screen in 2016’s Doctor Strange, the director now finds himself back in, well, Sinister territory with this, his horror comeback. There’s ultra-dark subject matter. Ethan Hawke in a major role. Regular co-writer C. Robert Cargill back on scripting duties. Jason Blum as producer. Scott Derrickson is home again.

Following his foray into multi-million-dollar blockbuster territory, The Black Phone is not so much a step back for the director as it is a film about looking back — at what home really is; at Derrickson’s own upbringing; at the forces (and friendships) that forge us into who we are. The ideal prism through which to explore these ideas is Joe Hill’s short story, taken from his 2005 20th Century Ghosts collection, resulting in an adaptation whose bleak premise and personal demons coalesce into a surprisingly warm, hopeful, and — yes — scary film.

Derrickson has spoken much about his own childhood in relation to The Black Phone, having grown up in a scuzzy ’70s Denver neighbourhood suffused with violence. It was a time not just of physical parental discipline and bloody, kid-on-kid backyard beat-ups, but one in which the spectre of Ted Bundy (who committed several murders in Colorado at that time) loomed large. All of these forces swirl around The Black Phone’s central figure of Finney, excellently played by Mason Thames in his big-screen debut. He’s an almost-teen growing up in scuzzy ’70s Denver, where his alcoholic father regularly brandishes his belt as a whipping tool, bullies wait round quiet corners to ambush him, and the local urban legend of child-catcher ‘The Grabber’ adds an ever-present threat of abduction. Even before he’s held captive in The Grabber’s basement, Finney lives in the shadow of danger.

Derrickson’s film spends a reasonable amount of time in the outside world before trapping its central character in stark, concrete walls — evoking the time and place with a Linklaterian ability to turn memories into movie scenes. ’70s rock pounds on the soundtrack (The Edgar Winter Group’s ‘Free Ride’ can’t help but evoke Dazed And Confused), bottle rockets soar, and kids brag in bathroom stalls about seeing The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. It all feels fondly remembered — but that warmth sits side-by-side with the ever-present threat of physical and emotional torment, and tales of boys vanishing with black balloons left at the scene. Derrickson evokes both the nostalgia and the nastiness with skill, neither one negating the other.

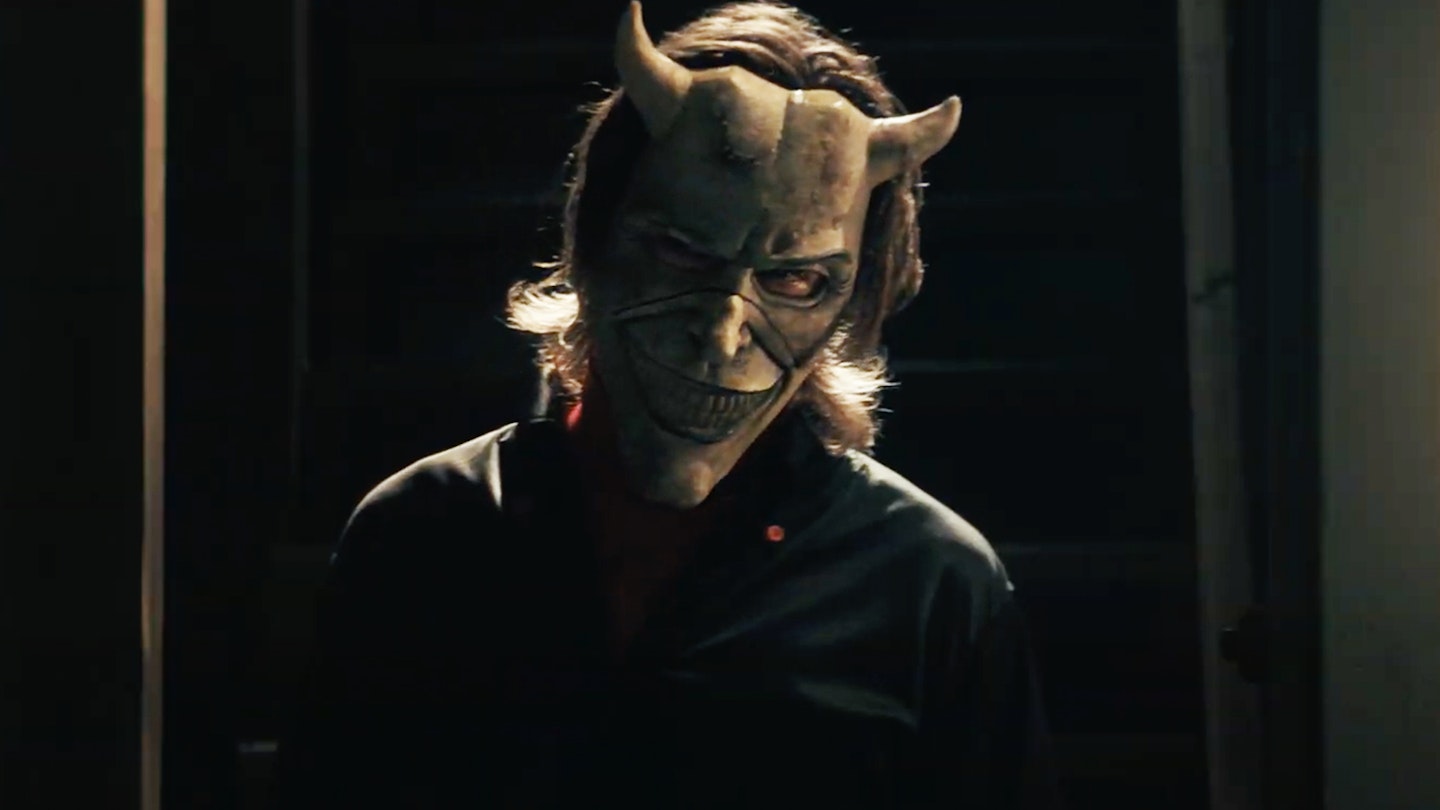

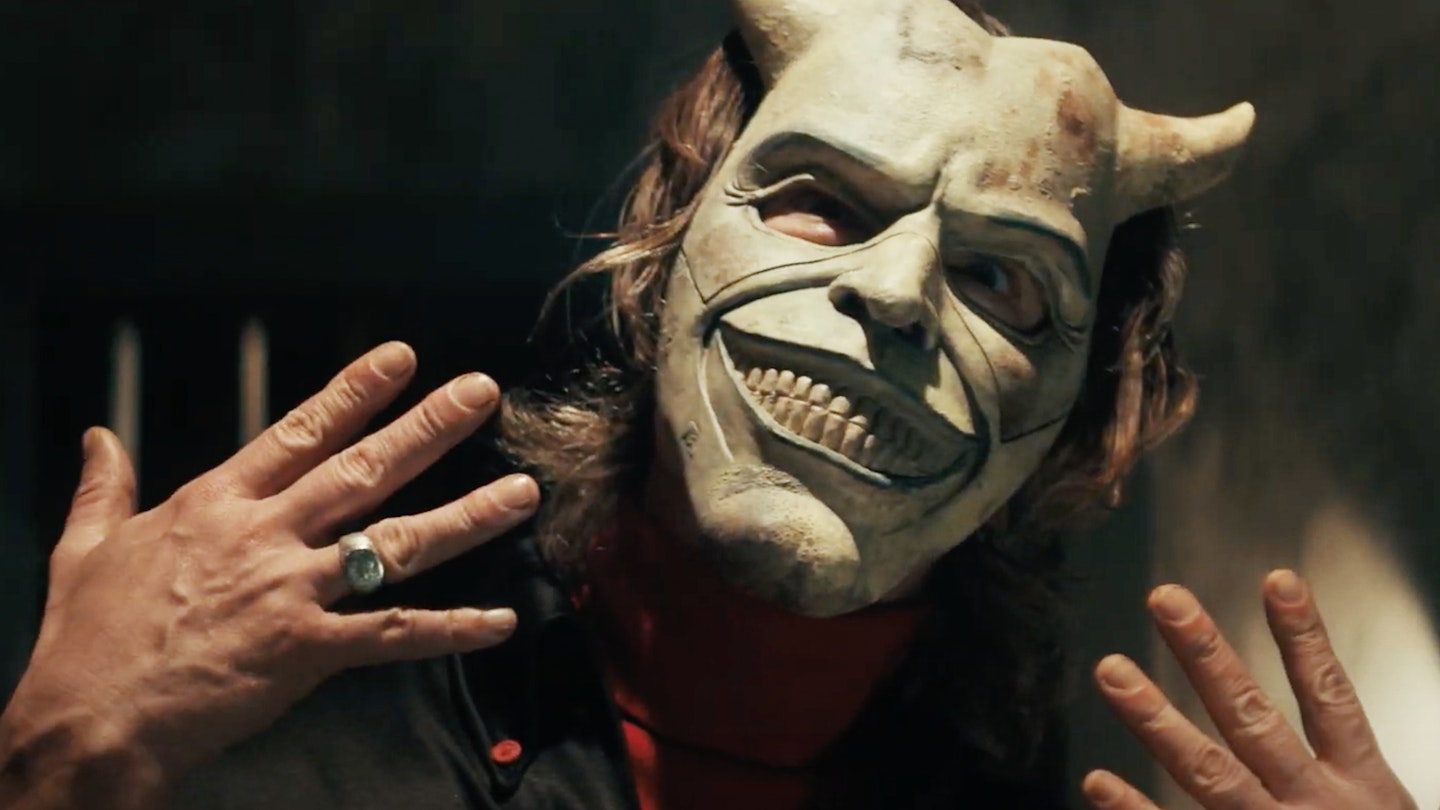

Hawke becomes one with The Grabber's masks, perfectly moulded to his facial contours. It’s hard to look away.

Once The Grabber bundles Finney into his black van, the film dials in on its central conceit: that the killer’s former victims can speak to the boy from beyond the grave through a disconnected landline attached to the basement wall. It’s here that The Black Phone plays like the darkest possible iteration of an Amblin movie (yes, darker than IT), as child ghosts call up to help Finney escape a similar fate. Hawke, in a rare villain role (albeit his second this year, post-Moon Knight), gives a frightening and fascinating physical performance — since his face is masked for almost the entire movie, it’s his presence (sometimes dominant, sometimes playful, always creepy) and vocal work that most impresses. He swaps out the upper and lower portions of his devil-horned mask like some fucked-up psychological exercise — donning frowns that feel more like snarls, or malice-dripping Man Who Laughs grins. Sometimes, he exposes his eyes or mouth entirely. Hawke becomes one with those masks, perfectly moulded to his facial contours. It’s hard to look away.

The Black Phone’s effective jolts and jump-scares should quell summer crowds looking for a straight-up scarefest, but it’s the dread that’s most palpable — the spectre of waiting for repercussive violence, whether in Finney’s attempts to escape The Grabber’s basement, or when anticipating his father’s wrath. And the salvation from all this is companionship; from the lingering ghosts of fellow kids, or Finney’s psychic sister Gwen (Madeleine McGraw, also excellent), who dreams in Super 8 and delivers perhaps the greatest cinematic prayer of 2022: “Jesus: What the fuck?!”

While there are occasional tonal missteps — James Ransone’s brief supporting character Max, conducting his own Grabber investigation, feels out of place — The Black Phone manages to be a mainstream genre movie that also feels deeply personal and impassioned. It’s horror, delivered with considerable heart. Welcome home, Scott.