Back in 1986, when Stephen King first wrote It, his seminal 1,138-page horror epic about a clown-demon terrorising a small New England town, he probably wasn't thinking about search engine optimisation. Pity, then, the poor studio marketers hoping to gain Google ranking traction on a widely used third person singular pronoun. But, as it turns out, the Warner Bros. marketing team needn’t have worried: as that record-breaking trailer attests, Pennywise The Dancing Clown holds a deep-seated cultural cachet, and this latest adaptation from Mama director Andy Muschietti meets that huge expectation like a perma-grinning demon meeting an unsuspecting victim.

It ranks among the better Stephen King adaptations — no small praise indeed.

This is emphatically not the Tim Curry-starring made-for-TV adaptation from 1990. There are deferential little nods here and there — a likeness of Curry’s costume can be glimpsed in one scene, and the iconic opening sequence, with the paper boat of doom, seems nearly identical — but Muschietti’s version feels distinct, discarding the back-and-forth timelines for a straightforwardly linear story (the grown-up portion of the story reserved for a potential sequel), wisely dispensing with the book’s bizarre pre-teen orgy, and shifting things along by 30 years or so, from the original ’50s setting to the more Amblin-esque ’80s.

The result: a coming-of-age yarn not unlike a horror-inflected jumble of The Goonies and E.T. (plus, inevitably, Stand By Me — another King adaptation). Which means the kids are important, and Muschietti is patient enough to devote precious screentime establishing each member of the Losers’ Club and their respective dysfunctional lives. There’s a lot of exposition to get through, but each of the seven losers gets their due, and the result is a truly well-rounded ensemble, as awkward and romantic as they are foul-mouthed and funny. Credit must go to the young cast, among whom there is no single weak link; it’s as authentic a portrayal of children staring down the barrel of adolescence as you’re ever likely to see.

Crucially, the personal strifes that each of the Losers face, from hypochondriac mothers to sexually abusive fathers, are filmed with just as much menace and horror as the supernatural scenes, and are arguably more disturbing. This is It’s great strength: it wants you to care about these loser kids, invites you to share in their deep angst, and bolsters the facing-your-fears allegory by being, fundamentally, a human drama first and a supernatural horror second.

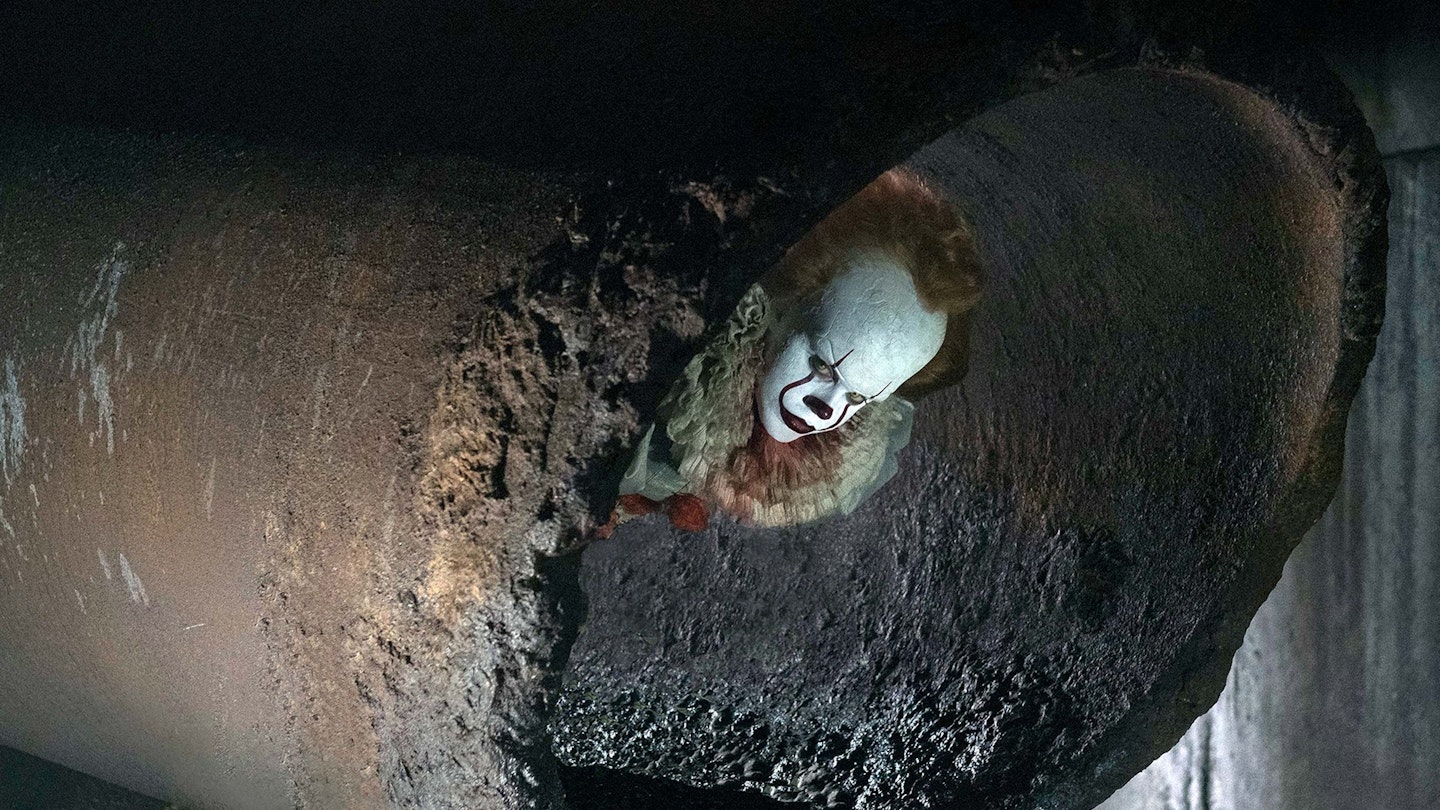

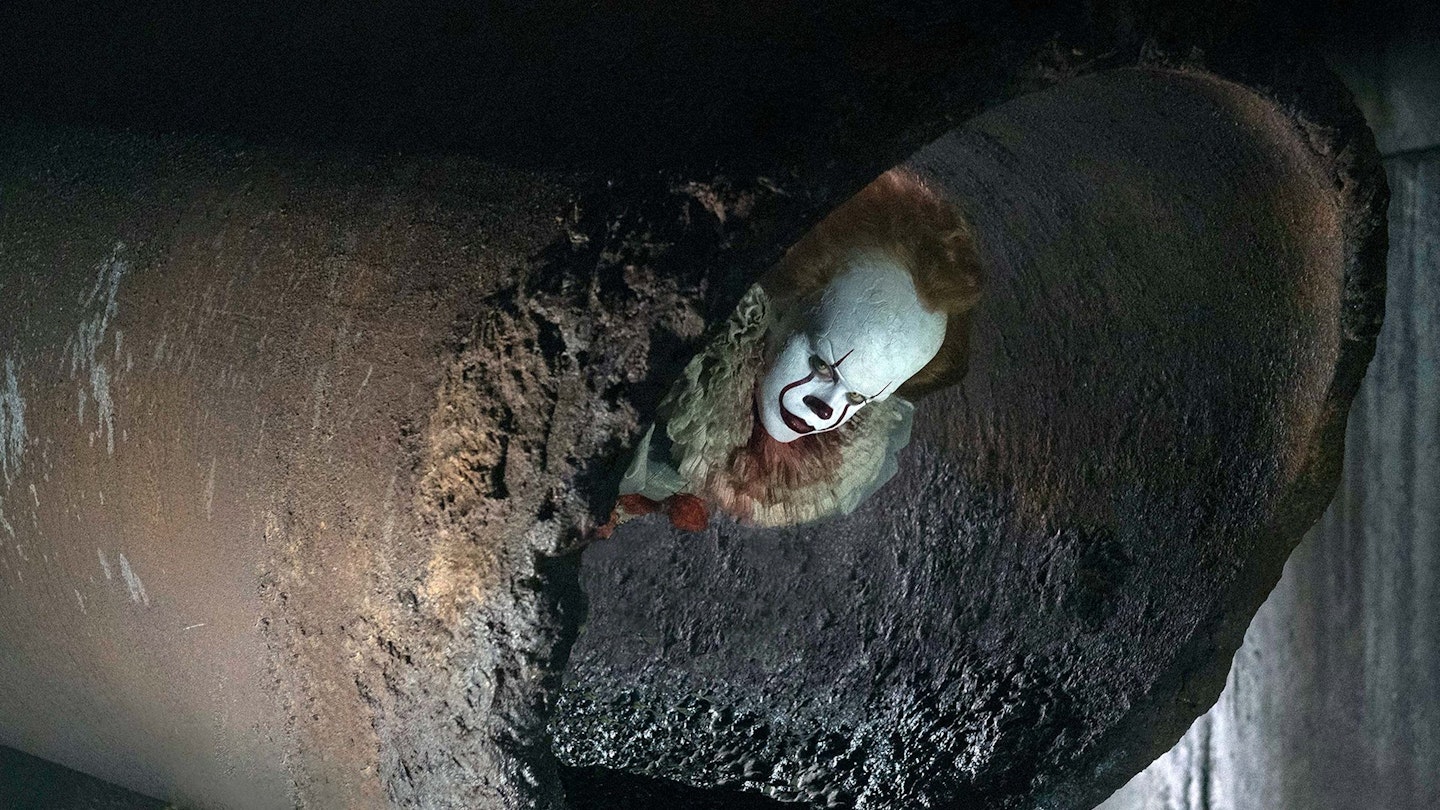

Which is not to say It disregards It. Just as Tim Curry’s larger-than-life performance anchored the 1990 version, so Bill Skarsgård proves the centrepiece of the 2017 vintage. Like the dinosaurs in [Jurassic Park](https://www.empireonline.com/movies/jurassic-park/review/, Pennywise is generally used carefully and sparingly, and is all the more powerful for it. With his cracked porcelain forehead, mucky Victorian scruff and giant protruding bottom lip, this Pennywise is a triumph of make-up and design as much as anything else – but despite his minimal screen time shared with prosthetic artists and CGI compositors, Skarsgård leaves a hell of an impression. His performance is full of strange nuance and wit, with subtle touches — like a fine trickle of drool hanging forebodingly from his mouth — making this interpretation more fascinatingly entertaining than truly disturbing.

How scary is It? That depends on your horror threshold. Seemingly oblivious to any recent trends in the genre, Muschietti seems content to go with the most straightforward horror tropes, opting for jump scares, whip pans and Psycho strings from composer Benjamin Wallfisch. There’s nothing wrong with a cliché if it’s executed well, and some of the practical effects are executed astonishingly well — most notably, a nuclear-level explosion of blood, acting as a brilliantly unsubtle puberty metaphor. Only occasionally does the film struggle to escape the sort of easily-avoidable peril that Scream mocked — as when the gang merrily wander into a haunted house, and are surprised to find it haunted.

If the horror sequences sometimes feel obvious, it’s perhaps because King deliberately leaned on those tropes. It’s power to scare, ultimately, is not as strong as its power to evoke the joys, confusions and fears of childhood, or its power to leave you wanting more. In a cinematic landscape weighed down by increasingly unnecessary franchises, you’ll leave It desperate for a sequel — something of which a marketing department charged with promoting a two-lettered film could only have dreamed.