The list of great British prison films is not long. You might go back to Joseph Losey’s hard-hitting 1960 drama The Criminal, starring Stanley Baker, and from there, for a laugh, you might zoom forward to 1979’s big-screen sitcom adaptation Porridge, starring Ronnie Barker as the wily, Sgt. Bilko-like inmate Norman Stanley Fletcher. But you won’t get much better than that same year’s Scum, directed by legendary cult British director Alan Clarke. Commissioned by the BBC, banned by the BBC, and, as a direct result, completely remade from scratch to get a cinema release, Scum was untouchable, a shocking, brutal piece of cinema about the reality of prison life for young men.

Released in UK cinemas shortly after Margaret Thatcher’s election as Prime Minister, Clarke’s film not only painted a brutal picture of the decaying borstal system for young criminals, it was also a none-too-thin allegory for the era’s wasted youth. For some 35 years, Scum remained a hard act to follow, and now here comes the first serious contender, the shock being not so much that it succeeds, but that the director responsible — the amiable David Mackenzie, whose most commercial film so far may be the offbeat coming-of-age story Hallam Foe — doesn’t have anything else remotely like it on his CV.

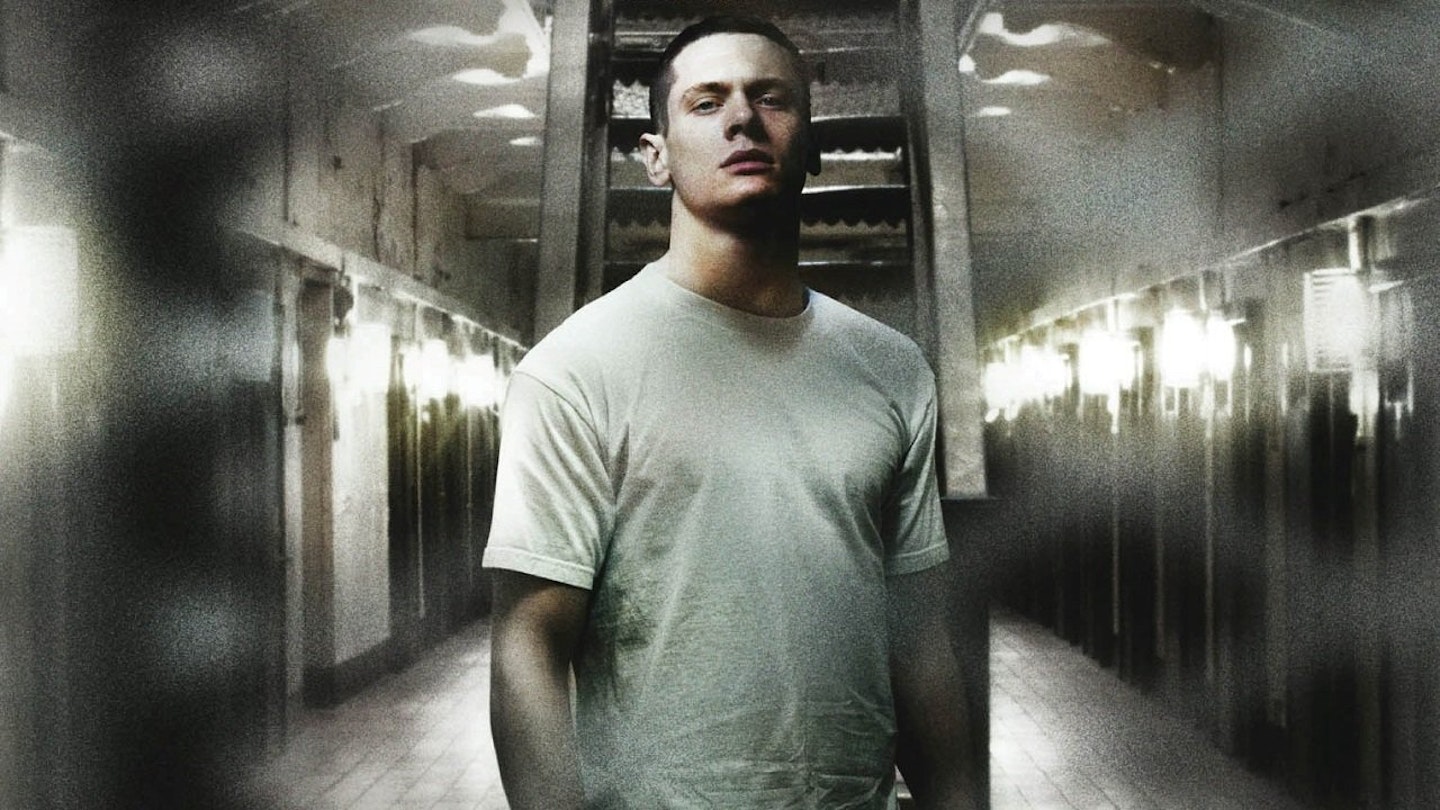

Set in the modern day, Starred Up deals with another controversial, archaic practice: when violent or disruptive youths are transferred to adult prison, their files are marked with stars that identify them as troublemakers. And right from the off, Jack O’Connell’s lower-working-class boy Eric is definitely a troublemaker, surly and truculent, passing defiantly through a humiliating induction. In these bleak opening scenes, we not only feel the dehumanising limbo of going under lock and key, we also get a hint of the simmering violence that rages in Eric’s veins — and it doesn’t take long for this to reveal itself.

The forensics of prison violence are unsettlingly compelling. Eric puts mundane items such as a toothbrush, a light bulb and even baby oil to nefarious use, just as Scum’s Carlin (Ray Winstone) made unforgettable use of a sock and a snooker ball. But this isn’t an exercise in aggro porn; Mackenzie gives us just enough of a taste of it to show what kind of boy Eric is: tough and unyielding, he is, as David Bowie once sang, “immune to your consultations”. And to this end we have Rupert Friend’s volunteer worker Oliver, a dishevelled do-gooder who tries to help and gets nothing but abuse from the sneering, totally self-sufficient Eric.

This in itself would be the stuff of a decent movie, since the dynamic is not the usual Good Samaritan story: the drama comes from just how resistant Eric is to letting anyone in. Oliver throws everything he has at this problem, and much as we want even just the smallest part to stick, Eric isn’t having any of it. Friend is probably the best he’s ever been here, and he really paints the bitter frustration of a man trying to make a difference while knowing he’s not wanted. Much like Eric’s, Oliver’s backstory is only thinly sketched, but there’s enough that’s alluded to, enough to give his character a painful arc by way of counterpoint.

Nevertheless, this is far and away O’Connell’s film, and it’s shocking how far he gets without bulking up. Eric isn’t particularly physically intimidating — like Winstone in Scum, say, or Tom Hardy in Bronson — but he’s certainly dangerous. There’s little fat on his bones, and a thousand-yard stare in his eyes that he turns on everyone, from the inmates to the screws and even the prison management. If A Clockwork Orange hadn’t been effectively a satire it might have looked something like this: the face of young rebellion, unimpressed by authority, ready to fight back and unafraid of the consequences. Quite what O’Connell is channelling here frankly doesn’t bear thinking about.

However, there’s a little twist in the tale that makes this more than a grim social-realist drama. Oliver isn’t the only one looking out for Eric’s best interest; there’s also Neville (Ben Mendelsohn), a thin, wiry fellow con. It takes a little while to sink in, since Eric resists his approaches as much as anyone, but Neville is Eric’s father, an established face on the wing. The relationship is as startling as it sounds, but soon reveals a completely dysfunctional logic: Mendelsohn, a tremendous actor, is the kind of father you might need under the circumstances, just not the kind you’d ever want outside of them.

With the characters in place, Starred Up works for the most part as a sensory experience of hell, where the vicious rule and the bad guys get trampled under foot. A plot by the wardens to deal with Eric gets a little out of hand, boiling over into scenes of pretty implausible melodrama, but for the most part this is a naturalistic and surprising soulful story in which redemption always lies far away on the horizon. It’s a tough watch, but Mackenzie’s film is a necessary snapshot of our times, not just a great prison movie but a devastating critique of a society that cares little for youth, and so much less for the underprivileged.