If anything holds back science-fiction as a film genre, it’s the tendency of big-studio thinking to use the genre as a disguise for other kinds of movie. Even classics of science-fiction cinema turn out to be Westerns, horror films or swashbuckling fantasy adventure dressed up with rayguns, spaceships and aliens. The theory goes that audiences don’t want to think too much, and science-fiction is a literature of ideas — so do a cop shoot-out on an abandoned asteroid or a mismatched partner romcom with a neurotic single chick and a handsome robot rather than risk something head-scratching. Ridley Scott, Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, for all their influence in the genre, have surprisingly little interest in science-fiction – though James Cameron does. You can tell the difference because filmmakers who just want to pretend say “sci-fi”, while those who mainline the pure product say “s-f”.

With Moon, Duncan Jones established himself as a potential great hope of s-f cinema, a director who actually wants to make science-fiction science-fiction movies. With Source Code he is back on Earth, and tackling a sub-genre which has plenty of recent precedents. Scripted by Ben Ripley, who has a track record in sci-fi thanks to a couple of direct-to-the-dungeon sequels to Species, this time-tripping, mind-warping exercise evokes everything from Groundhog Day to Déjà Vu. A lovely, generous piece of cameo voice-casting in a key offscreen role even pays homage to a specific television show, and justifies entirely an otherwise by-the-numbers tipping-in of the estranged-father-and-son angle which is almost obligatory in a Hollywood movie (do all screenwriters have baseball coach dads who disapproved of them staying indoors and typing?).

Otherwise, it’s brilliantly constructed, going over an eight-minute cycle again and again with variations, each time advancing the plot — it may be that stories like these were inconceivable before choose-your-own-adventure books or computer games — but also bringing out the tragedy of a doom we are told is inescapable as the time-hopper makes different, deepening connections with the girl sitting next to him.

Yes, it’s clever enough to make you break out a pad and pencil to work out how the jumble of timelines intermesh — raising the question of whether this slice of the past (the source code of the title) is a ‘read-only file’ or can be affected by the actions of a time-traveller who yearns for a happier outcome. But it’s also warm enough to make you care what happens, especially to the girl who repeatedly gets blown to pieces just as she’s on the point of changing her life. Source Code is cannily cast with folks who’ve more than demonstrated their abilities, but have yet to attain the star status they deserve. Michelle Monaghan (Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, Eagle Eye) and Vera Farmiga (Orphan, Henry’s Crime) have been brilliant in enough mid-list pictures to get noticed (and Farmiga a bit more in Up In The Air), but haven’t yet landed the top drawer material that would make them proper movie stars and put them in line for serious awards. Here, the women shine in good, secondary roles: Farmiga makes so much of her trim-uniformed part, which is mostly plot set-up and the glint of a tear in an icy eye, that you wonder what she might not be able to do if allowed to cut loose, while Monaghan is fresh and appealing in a way which sells the concept that someone might fall so deeply in love with her that he resolves to challenge the fundamental laws of the universe inside eight minutes.

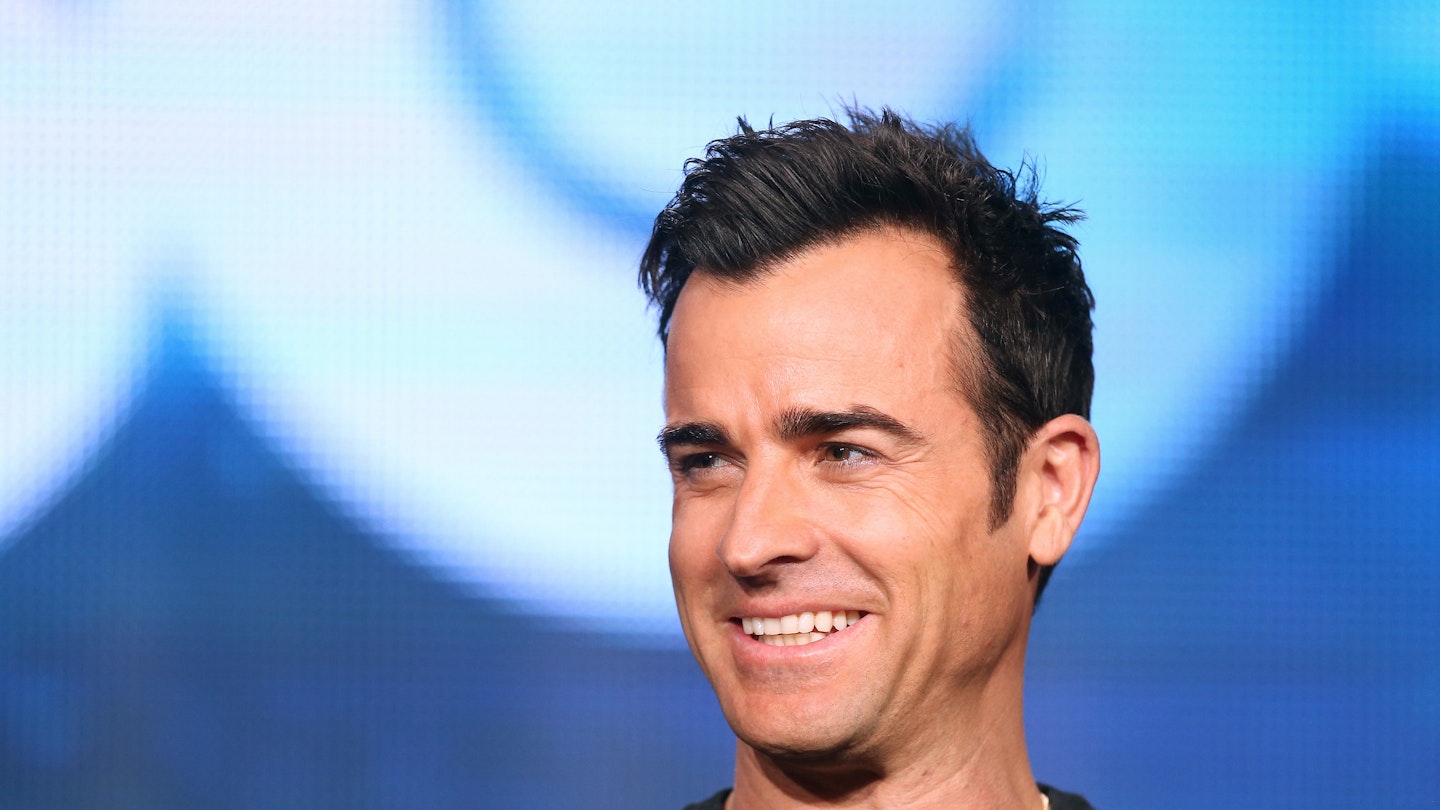

However, the solipsistic nature of the head-trip, subjective-reality sub-genre means everyone aside from the hero has to hold back something, and all the pressure is on the leading man. Jake Gyllenhaal builds on his curious, committed time-tripper act from Donnie Darko and his wide-eyed-yet-gung-ho military hero bit from Jarhead. Indeed, as he runs through the moebius loop paradoxes of the plot, he’s even returning to the resourceful-acrobat-tampering-with-the-laws-of-time gambit of Prince Of Persia: The Sands Of Time, the big-budget flop he needs to bounce back from with this less costly, more rewarding vehicle to save his own immediate future. Gyllenhaal shows immense range as he bounces around a train carriage and a group of significant bit-parts while playing the same set-up for film noir neurosis (there’s an early feint about amnesia), cracked comedy (when he snarls, “Are you a comedian or something?” at an angry wiseass, it turns out the guy actually is), action-man intensity (there’s a gun to be got out of a secure locker), tragic angst (Stevens is progressively sidetracked by his own MIA circumstances) and cerebral detection (so, where’s the suspect device?). There are minor puzzles and red herrings within the basic who-is-the-mad-bomber? premise (several suspicious passengers get their moments), but the gimmick gradually settles down as the film latches instead onto the hero’s argument with the laws of quantum physics as to whether ‘source code’ is immutable.

Jeffrey Wright’s limping, rasping Evil Physicist Genius imports a necessary broad stroke of melodrama (and thickly sliced ham), and a few relatively newminted clichés (like the nervous Muslim commuter who is everyone’s first-choice terror suspect and therefore bound to be an innocent — or is he?) set up short-cuts which keep the complex story moving. A race-against-the-clock element, with downtown Chicago threatened with irradiation, limits the number of times Stevens can be sent back to try again (like the number of lives in a computer game), but also justifies the way his superiors keep vital, distressing information back to keep him on track (where is the capsule-like pod, with its dodgy wiring and problem heating unit, to which the hero returns between his trips to the immediate past?). This is the sort of clever-clever picture which requires multiple viewings to put all the pieces together, though it’s also got enough action (the same explosion, several times) and heart (courtesy of Monaghan and Farmiga) to make it as affecting as it is ingenious. It plays fairer than the very comparable Déjà Vu, and delays its final decision about the precise resolution of its hero’s quandary ’til the last moments — which, moreover, satisfy without copping out.