A fast-cut trailer, a glossy poster, a big-spend marketing campaign… Hollywood has plenty of tricks up its sleeve to sell audiences something that isn’t actually there. Such was the case in the US with Solaris. It’s George Clooney. It’s Steven Soderbergh, hot off the back-to-back successes of Ocean’s 11, Traffic and Erin Brockovich.

But Solaris is really a slow, meditative psychodrama set on a space station. Sensing box office disaster, 20th Century Fox decided to mis-sell the movie as a sci-fi love story. The crowds came but, understandably, left angry and confused. Positive word-of-mouth was zero. The film died.

Solaris also comes burdened with another weight of expectation, albeit from an entirely different direction. Based on a novel by Stanislaw Lem, an earlier version was made in 1972 by Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky. His is a ponderous piece of art cinema, much beloved by film masochists for whom no work can be too slow, no detail too painstaking. This critically obsessive audience isn’t exactly going to warm to the idea of someone who used to be an incurable Casanova in a TV hospital soap soiling their original, much-loved masterpiece.

None of this does Soderbergh any favours. And so, quite correctly, he just went out and made the movie he wanted to make.

Solaris is a measured piece in a classic filmmaking style. The content of every shot is carefully constructed, while every cut is timed to the exact milli-second. Music is used sparingly, and at times only rainfall or machine noise quietly fills the soundtrack. This is how Soderbergh subtly sets the scene in order to ask big questions about life, love, pre-determination, religion and free will.

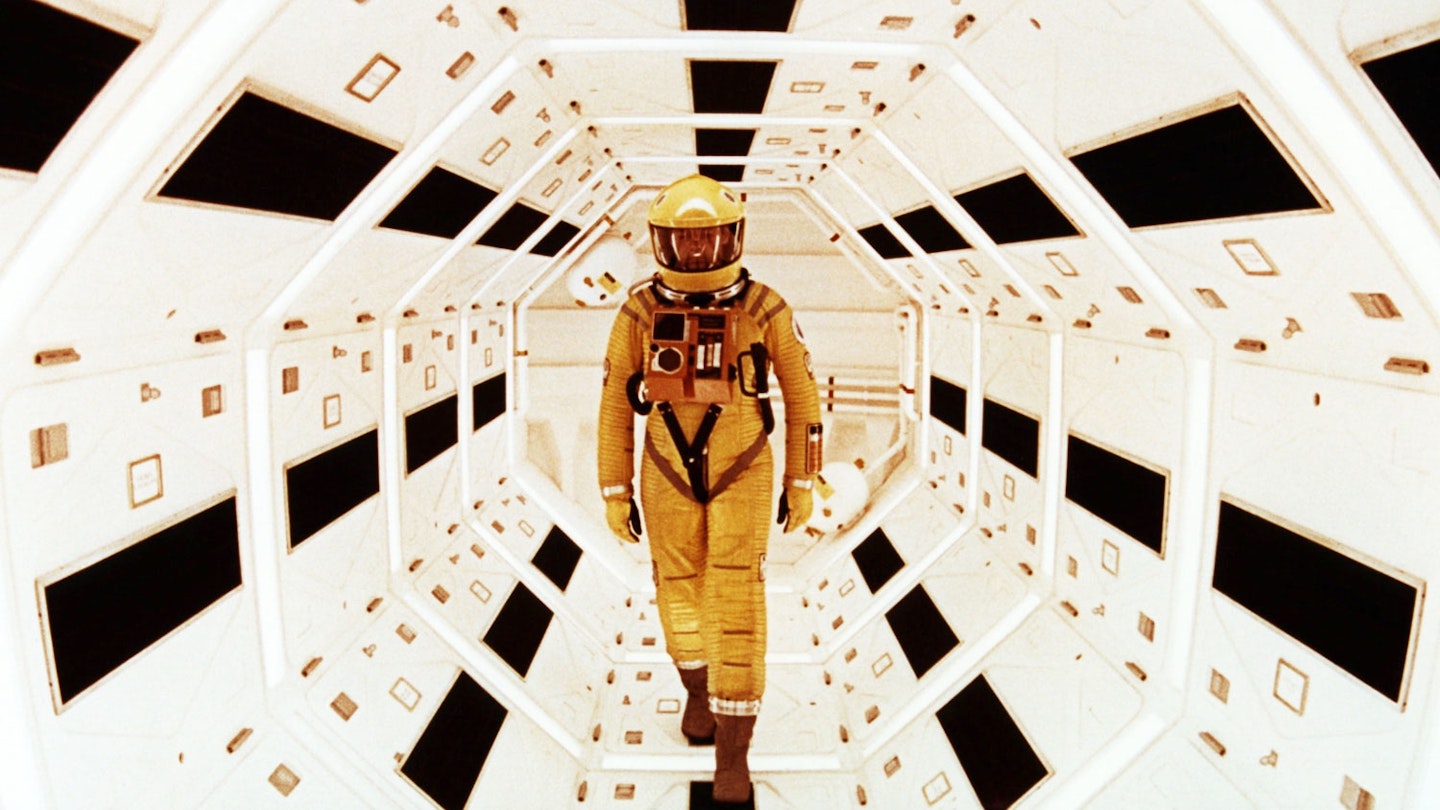

Solaris is proper, grown-up science-fiction — an attempt to examine some of the major philosophical issues of the present day by setting them in a recognisable future. No lightsabers or alien wars here. Instead, the space station design is functionally minimalist, and the planet — cloudy blues and pinks threaded with darker veins and electrical lines — like a huge colour scan of a human brain. Soderbergh leaves room in the movie’s running time to allow audiences to think and feel. It’s not an all-out barrage on the senses, but rather a delicate study of human grief that really does encourage us to examine our place in the universe.

As such, it’s surprisingly — but genuinely — moving, driven by stellar, understated performances from Clooney and McElhone. The film acknowledges the complexity of their marriage, of his feelings of guilt, of her return to ‘life’. Clearly Rheya’s reappearance is, emotionally, a double-edged sword — perhaps it can be more painful to regain the thing you’ve lost than to lose it in the first place.

As the film touches on imaginary childhood friends or the relationship between a being and its ‘higher power’ creator, it becomes psychologically, rather than narratively, compelling. This may not be the film everyone was expecting from Soderbergh and Clooney, but it’s a major landmark in their ongoing collaboration.