A Single Man is directed by fashion designer Tom Ford, the saviour of Gucci, a fashion brand-name in his own right, and that bloke who cavorted with Scarlett and Keira on the cover of Vanity Fair. Whatever pre-conceptions a fashionista-turned-film director might trigger — a film of high style full of impossibly good-looking people where mood trumps story —partially apply to A Single Man, but that doesn’t get anywhere near the whole picture. For Ford’s directorial debut, anchored by a career-best Colin Firth performance, has a strong shout at being the most thoughtful, deeply felt, moving movie experience of the year.

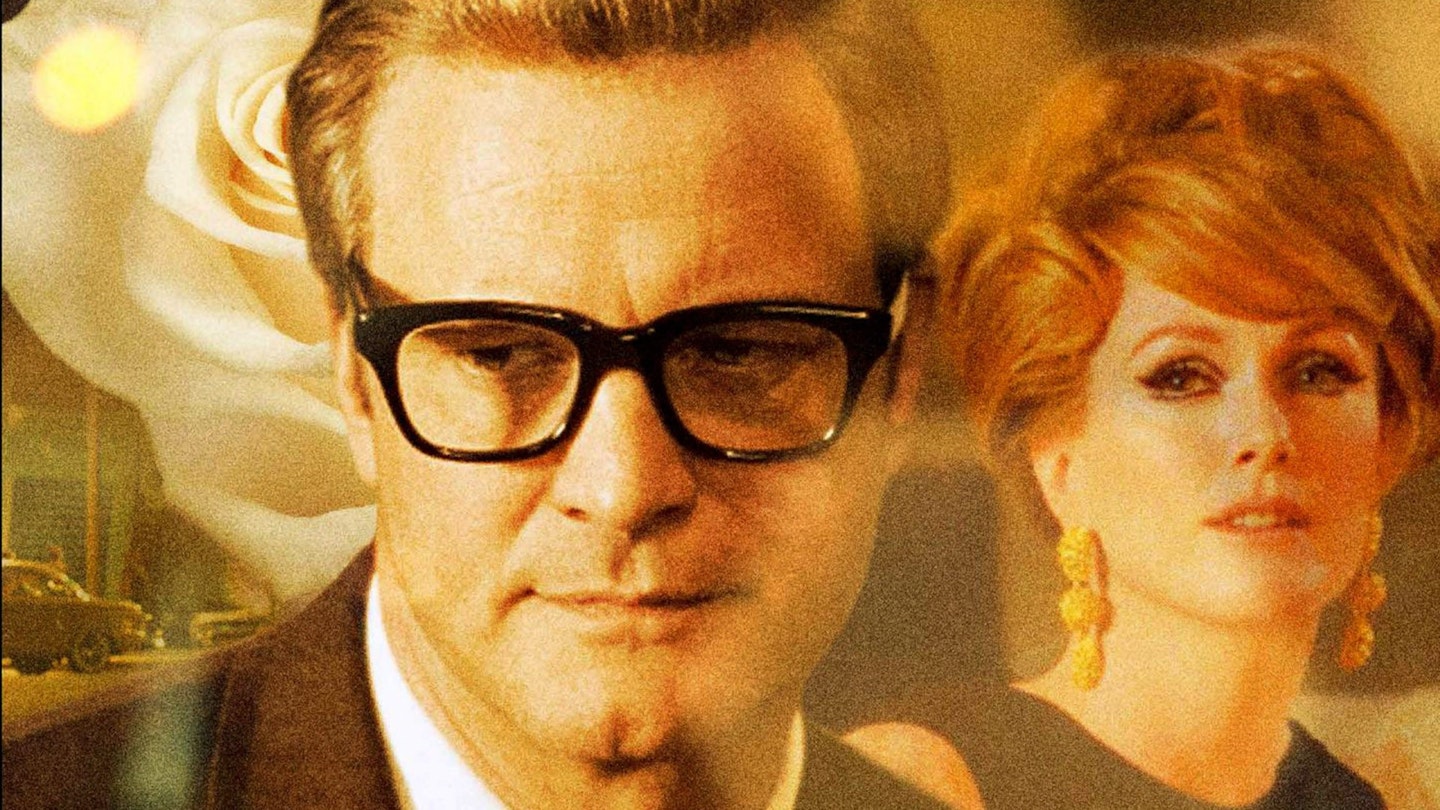

Based on Christopher Isherwood’s 1964 novel, Ford and co-writer David Scearce delicately map out the (potentially) last day in the life of college academic George Falconer, who can’t face his future having lost the love of his life, Jim (Matthew Goode), in a car crash. Rather than any histrionics, the film follows George’s almost Japanese ritualistic preparations for suicide (something not in Isherwood’s novel) and how real-life complicates them: a discussion about literature with student Kenny (Nicholas Hoult), whose glint in his eye suggests he has more on his mind than books; a run-in with an impossibly good-looking James Dean lookalike hustler (Jon Kortajarena), and, best of all, a boozy night in with old friend, London socialite Charley. Julianne Moore makes for a fantastic lush, lunging at George, conveying with Firth the entire feel and history of their relationship in a single scene.

As you might expect, Ford gets ’60s style down pat, but this isn’t period pastiche à la Far From Heaven. Catching small, sensual details to invoke the power of memory, Ford’s filmmaking is imbued with the precision of Hitchcock (the score nods to Bernard Herrmann), the coolness of Kubrick and the vividness of Wong Kar-Wai without ever being a slave to any of these influences. Occasionally his passions get the better of him — his penchant to use colour saturation to suggest how George’s day has brightened lacks the subtlety of the rest of his approach — but for the most part, this is impeccably composed, astonishingly self-assured debut filmmaking. A Single Man is patently a labour of love, and you can feel Ford’s commitment to the content in every frame.

Yet, in many ways, A Single Man really is Firth’s show. Sporting sandy hair and horn-rimmed glasses, Firth beautifully etches a man slowly detaching from his life. Perhaps the character’s biggest moment — receiving news of Jim’s death — starts with a clipped phone call and ends with a portrait of a man in bits, Firth making the transition without a false note. A model of economy and restraint, Firth starts addicted to his broken heart and ends a man capable of seeing the beauty in the world precisely because he has given up on it. He roots George, and therefore the rest of Ford’s beautiful film, in dignity.