When Sidney Poitier was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009, Barack Obama succinctly noted that the actor “does not make movies, but milestones”. He was always a talented actor — blessed with movie star looks, natural charisma, and a knack for choosing the right role — but more than that, he was a groundbreaking figure in the civil rights movement, a cultural force that made him an agent for change in a rapidly changing time.

That’s the dichotomy that Reginald Hudlin’s eminently watchable documentary looks to explore: the career as actor, producer and director, and the incalculable civil rights legacy it left. An impressive conveyor belt of A-listers — Denzel Washington, Spike Lee, Robert Redford, Barbra Streisand, Halle Berry, and Morgan Freeman among them — line up to tell the story, but perhaps most compelling is the testimony from the man himself, with interviews filmed shortly before his death in January 2022.

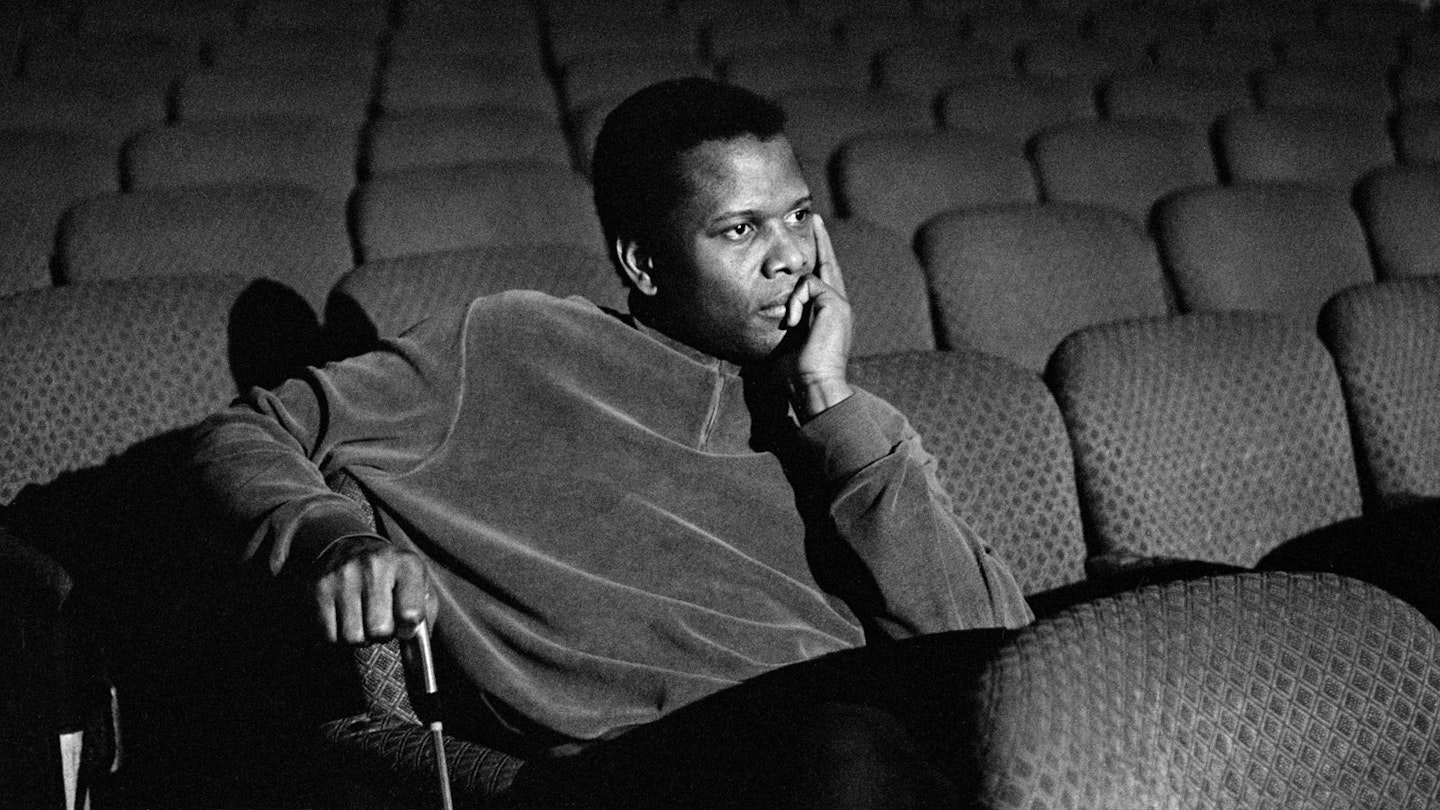

As you might expect, Poitier is an excellent storyteller. His voice might have grown gentler and quieter with age, but here he retains that commanding, mellifluous tone — an accent which, as he explains in the film, was self-taught from listening to radio announcers. Born two months premature to Afro-Bahamian tomato farmers, he reels off charming anecdotes of his none-more-humble beginnings, such as the first time he saw a car, or his bemusement at riding the New York subway for the first time.

More significantly, he remembers the first time he saw his own reflection. “I didn’t know what a mirror was,” he explains carefully, looking right down the lens. “Do you hear me?” he asks, rhetorically. It places his revolutionary career into sharper perspective: having grown up in a Black-majority Caribbean community, American-style racism was an alienating concept, and his youthful encounters with the Ku Klux Klan, among other injustices, set him on a specific path.

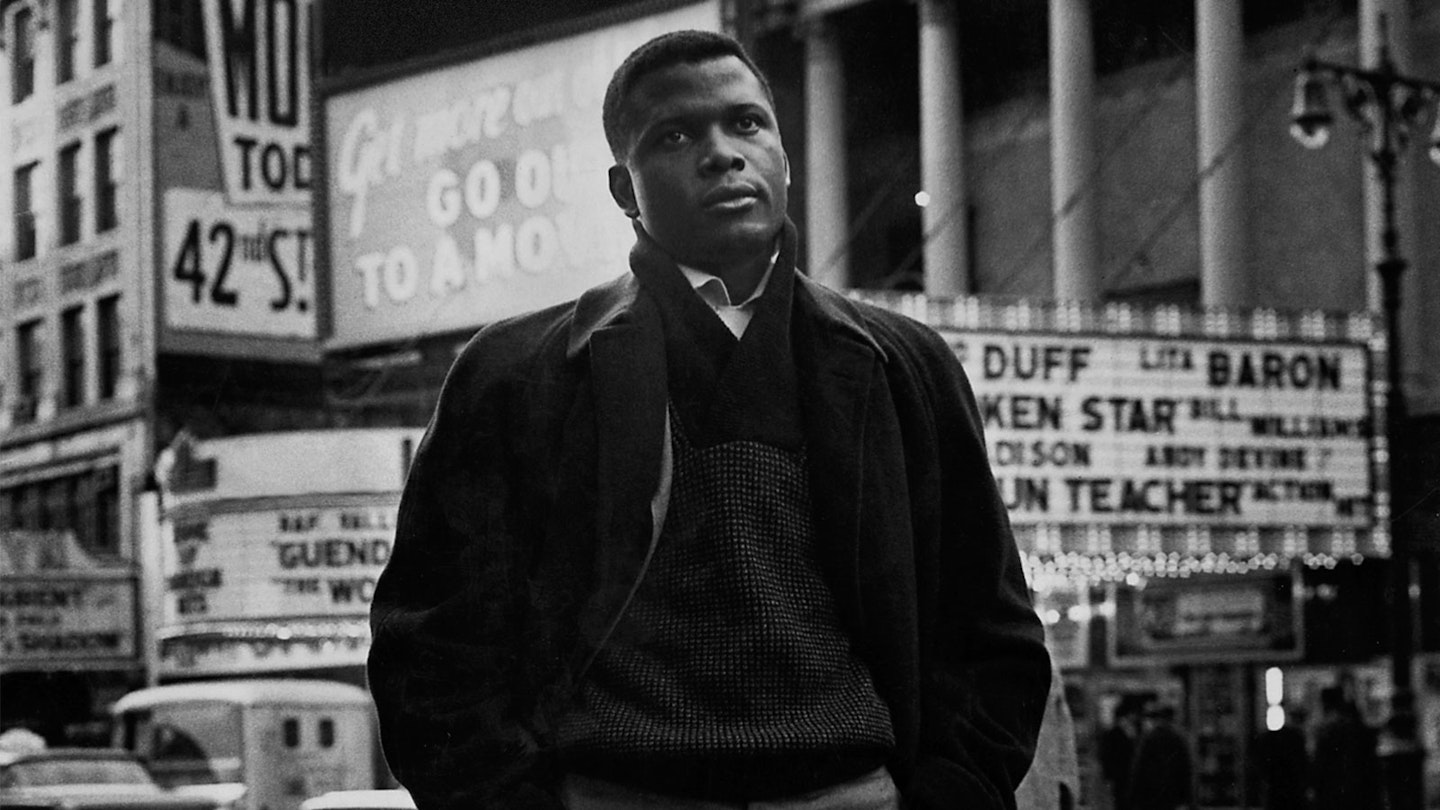

As the film diligently explains, Poitier explicitly avoided subservient roles and actively sought characters which had power and agency.

Hudlin’s film follows a straightforwardly linear route in its telling of that journey, with archive clips and talking heads taking us there. There are few surprises for those who know the story. But it is such a consequential life, in both the history of cinema and just history in general, that no embellishments are necessary. Poitier was a leading man at a time when that was virtually unthinkable in the segregation era; Black actors were largely relegated to discriminatory comic relief. As the film diligently explains, Poitier explicitly avoided subservient roles and actively sought characters which had power and agency. His work schooled white audiences, thrilled Black audiences, and quite literally changed the game.

The film is made “in close collaboration with the Poitier family”, which always risks sending things down the hagiography route. But in fairness, the film doesn’t shirk from the low points: his extramarital affair with his co-star Diahann Carroll, his occasionally testy rivalry with frenemy Harry Belafonte, or the later criticism he fielded from the Black community that he acquiesced to the “Uncle Tom” trope.

Ultimately, the film comes to a conclusion that seems hard to avoid: that Poitier was a great actor, a fine director (Stir Crazy remains among the highest-grossing films ever made by a Black filmmaker), a genuine history maker, and a fundamentally decent man. There’s a line from Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner that one of the talking heads, Oprah Winfrey (who also serves as a producer) marks out. It is a line, she argues, that defines Sidney Poitier: “You think of yourself as a coloured man,” Poitier says in the film. “I think of myself as a man.”