“If you wanted a rock ’n’ roll photographer, what would you call him?” asks the subject of this documentary rhetorically, about half an hour in. “You’d call him Mick Rock.” This is true. You would also probably make him six feet tall and beanpole-skinny, and add a mop of black hair, dark glasses to be worn at all times and a strong proclivity for cocaine. You’d have him once stay up “for seven days”. But most importantly, you’d have him be responsible for a great deal of the most important images any music photographer has ever taken.

The real stars of the show here are his pictures, and that is as it should be.

Like all the others, Mick Rock, now 69, straightened out and still working (in the final minutes here, we see him shooting Father John Misty) ticked all those boxes, but made his most emphatic mark in that last box. He took the picture of Lou Reed (kohl-eyed on the sleeve of Transformer). He took the picture of Iggy Pop (lithe and bathed in orange light on the sleeve of Raw Power). He took the picture of Queen (the four of them, Freddie Mercury’s arms crossed over his chest, on the sleeve of Queen II).

Most notably, he took the picture of David Bowie: on his knees at Oxford Town Hall in 1972, fellating Mick Ronson’s guitar. Ushering in the androgynous, pansexual era of glam, it is not an exaggeration to say that this photograph (coupled with his performance of Starman on Top Of The Pops later that year) was what made Bowie a star. No wonder Bowie, as Rock remembers here, came rushing over at the end of that show gasping, “Did you get anything?”

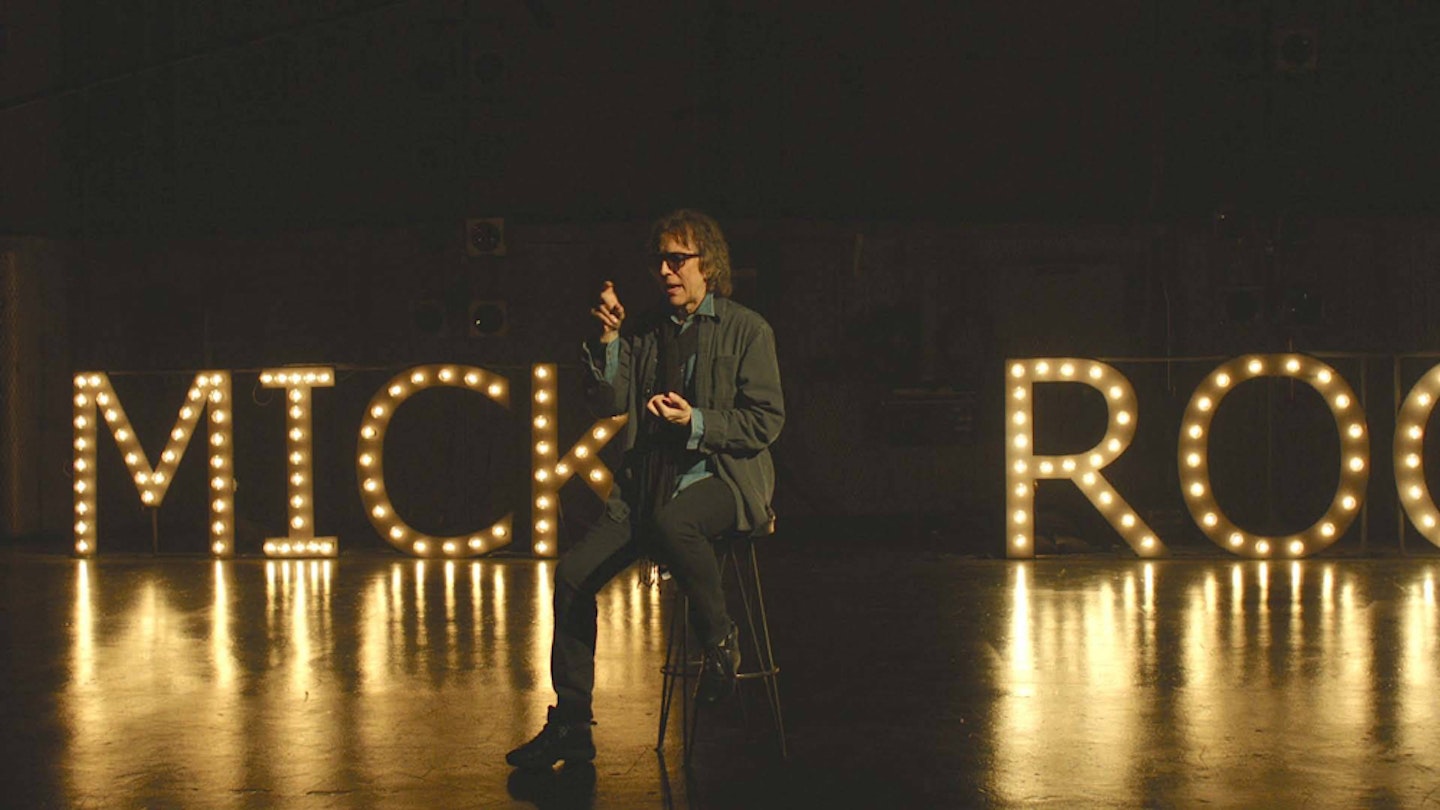

Rock’s story itself is an incredible one: and one that is knowingly played up here. From the off, he is presented as a star himself, charismatic and fond of pronouncements such as, “The lysergic experience opened up my third eye, you might say.” There is a recurring, dramatised sequence that finds a younger Rock on a hospital bed, breathing through a respirator after a drug-induced heart attack (shades still on). We hear taped conversations between him and Reed, and him and Bowie. We see him practising kundalini yoga (“I don’t think I’ve ever done a session without standing on my forehead beforehand”), and hear tales of gallivanting around the sleazy, late-night dives of New York, as much a part of the scene as a documenter of it. “I never felt like a voyeur,” he says. “I was always on the inside looking out.”

But the real magic comes when Rock is stood in front of a giant light box, telling the stories of his most famous works. It would be easy to put his legacy down to simply, serendipitously being in the right place at the right time: and indeed, he does at one point concede that “you couldn’t really take a bad picture” of David Bowie or Debbie Harry. But as Lou Reed himself notes in an interview at the very end of his days, his lifelong friend has created far too many, beautiful iconic images for it all to be down to luck. These are photographs that are every bit as vital to the story of music as any of the songs, albums or concerts that they accompanied. And for this, Mick Rock deserves a documentary — a great documentary like this one — as much as any of his subjects.