Buster Keaton's third and shortest feature ranks among his best. An ironic comment on social injustice, it's a deceptively serious study of fantasy and reality, life and art. But, most significantly, it's also a film about film that places so much stress on creativity and escapism that the dream sequence relegates the everyday to the margins.

The visual and clowning ingenuity required to execute such a sophisticated picture was matched by a technical assurance that was rare for a slapstick silent. Keaton's entry into the screen world of Hearts And Pearls, for instance, was a masterclass in comic montage that was not only perfectly timed, but also anticipated both the advances in editing usually associated with the Soviets and the surrealism achieved by such French Impressionists as Germaine Dulac and René Clair.

Indeed, not even the iconoclasts of the nouvelle vague attempted such a sustained assault on the conventions of screen storytelling, as Keaton did while passing from the prologue realms of Griffithian melodrama into a ciné-existence utterly devoid of linear logic and independent of standard spatial and temporal systems.

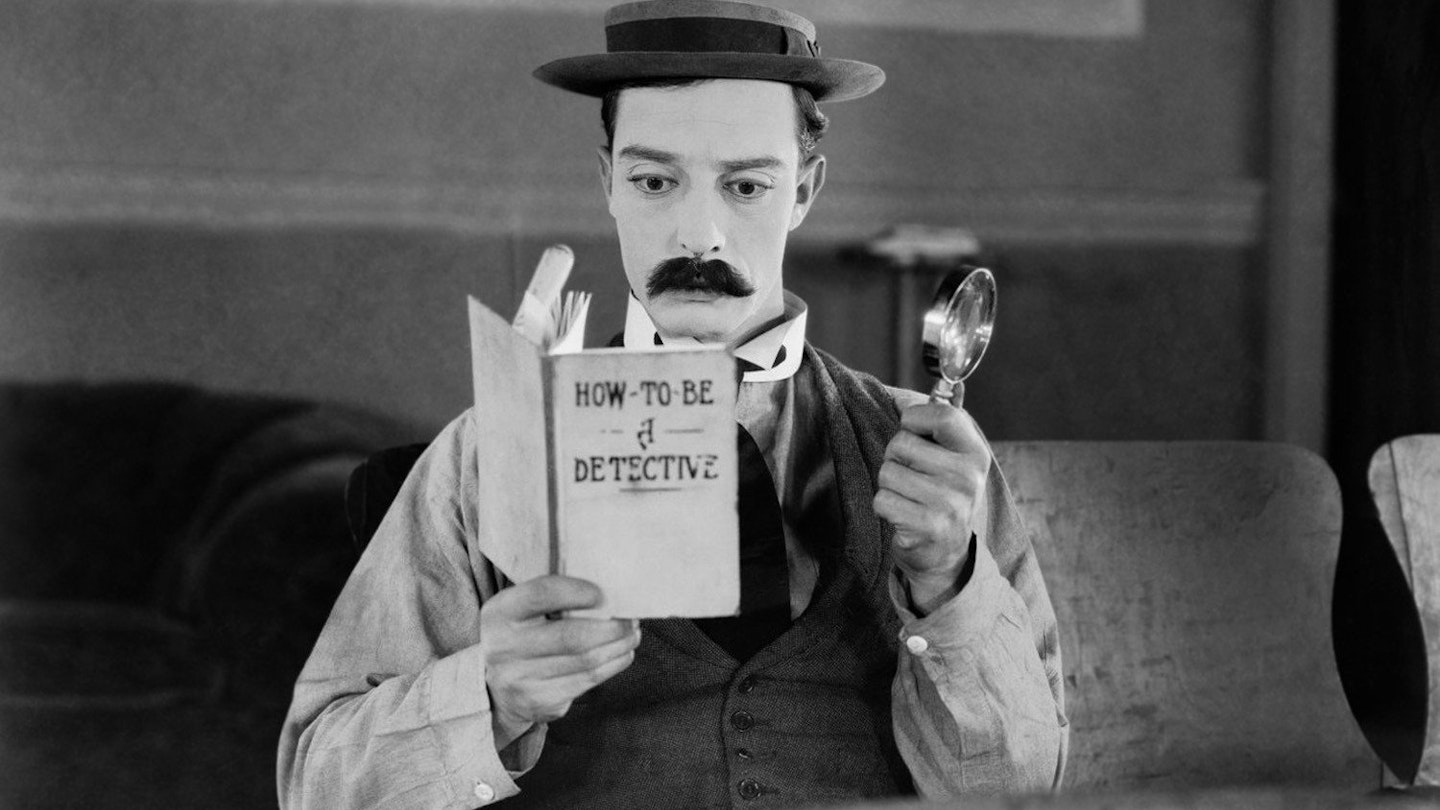

The cross-cutting between the house steps, garden, street, mountain ledge, jungle, desert, beach, snowbank and forest in this opening sequence is sublime and it's all framed within the nickelodeon proscenium, which Keaton proceeds to abandon as the projectionist acclimatises to his new surroundings and adopts the sleuthing persona he will require to find the loot.

However, in returning to a more typical narrative mode, Keaton has alerted us to the fact that anything might happen and it promptly does. The sequence in which Buster escapes with the pearls and dives into a box to escape in bonnet and crinolines was an old conjuror's trick, whose mechanics Keaton was prepared to reveal by filming it straight (albeit with the aid of some nifty set construction). But he withheld the secret of the stunning illusion that allowed him to leap through the chest of his valet and a locked barn door (which was achieved using dummies and trap doors) and, consequently, the effect remains more magical than anything since produced by CGI.