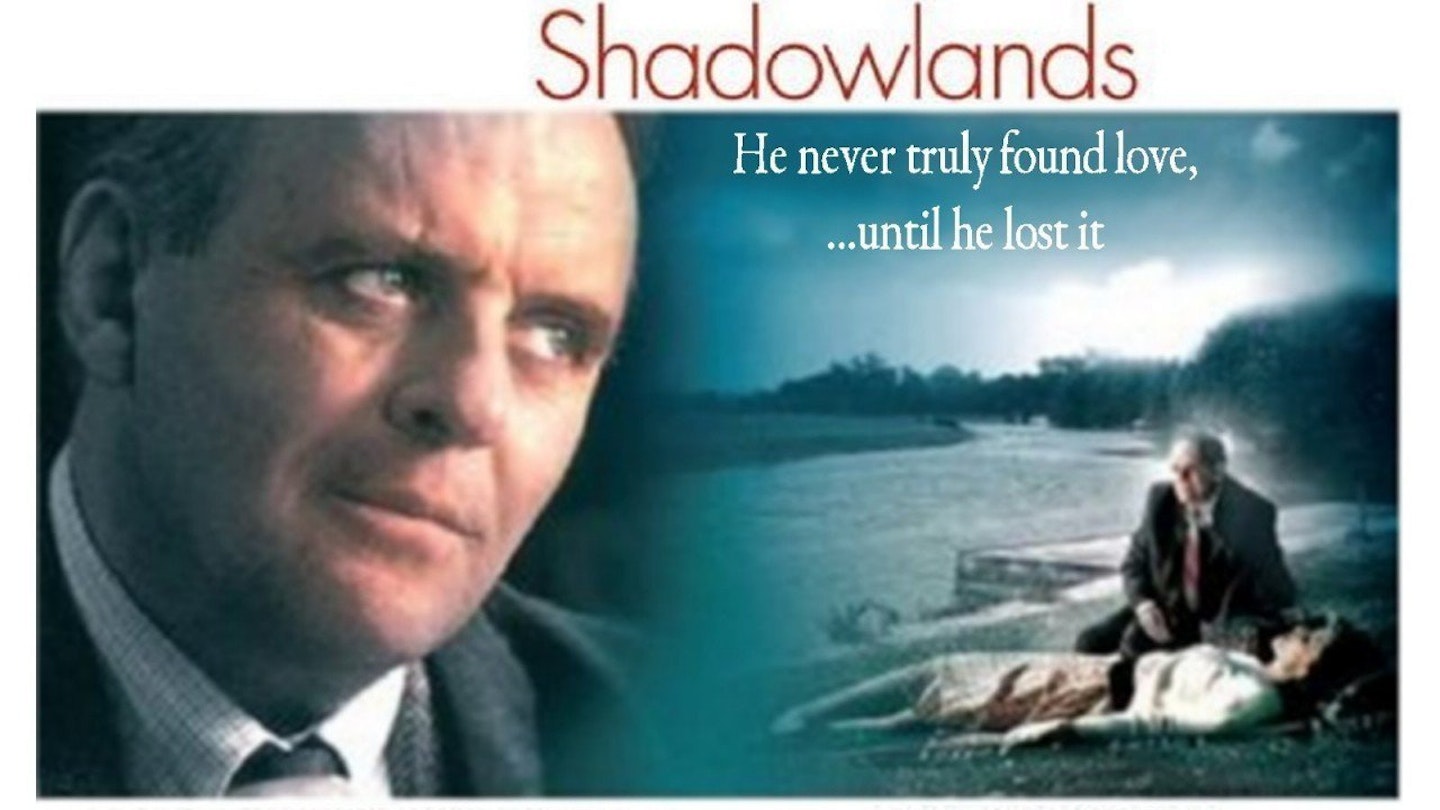

Anthony Hopkins and Debra Winger love and suffer to irresistibly sob-inducing effect in Richard Attenborough's handsome, moving, big-screen adaptation of William Nicholson's award-winning play, inspired by the late-blooming romance between the fiftysomething C.S. Lewis devout Christian, professor of literature, logician and author of wise and witty books that included sci-fi and the Narnia classics for children and American writer Joy Gresham.

For dramatic purposes, many of the facts, friendships and experiences of the real personalities are side-stepped: Lewis' comfortable affair with his housekeeper for instance, or that in reality Gresham had two sons, not the solitary, sad little soul touchingly played by young Joseph Mazzello from Jurassic Park. And yet, while the breadth of "Jack" (as Lewis was known) and Joy's intellectual accomplishments is barely conveyed, the essence of their profound relationship is.

What began as correspondence was formalised as convenience, so that Joy could remain in Britain. Somewhere along the way, however, it found resolution as deep, fulfilling love. This provides an affecting spiritual journey for Hopkins' Jack from vague, dry academic, philosophising under the spires of Oxford, to the thrill of needing someone else, through to the agony of watching her die of cancer and carrying on when his insides have been torn out.

Attenborough takes his time getting to the heart of the matter, although the meandering among the ivory tower dwellers of Academe is not without pleasure in a musty Magdalen where the Fellows are a tweedy peevish bunch receiving the unconventional, foreign, feminine Mrs. Gresham and an inferior claret with the same unwelcoming moues.

It may sound like a terrible thing to observe, but this really gets good with Joy's diagnosis of incurable cancer and Jack's despairing crisis of faith. For all its sorrow, and the pain of loss that Jack comes to accept as the cost of needing another, this is a wonderfully affirmative tale of love as the richest and most liberatingly meaningful experience in a thinking man's life, and an extremely compelling testimonial to living in the now.

Winger's forthright and challenging Joy is a warm, disarming and sympathetic portrait of a romantic forcing open Lewis' shell. As for Hopkins, this is another fastidiously perfect characterisation, perhaps even topping his recent mesmerising performances. This time he gets to let rip and cry, and by heaven, when he does, it's a sorry individual who won't be crying with him