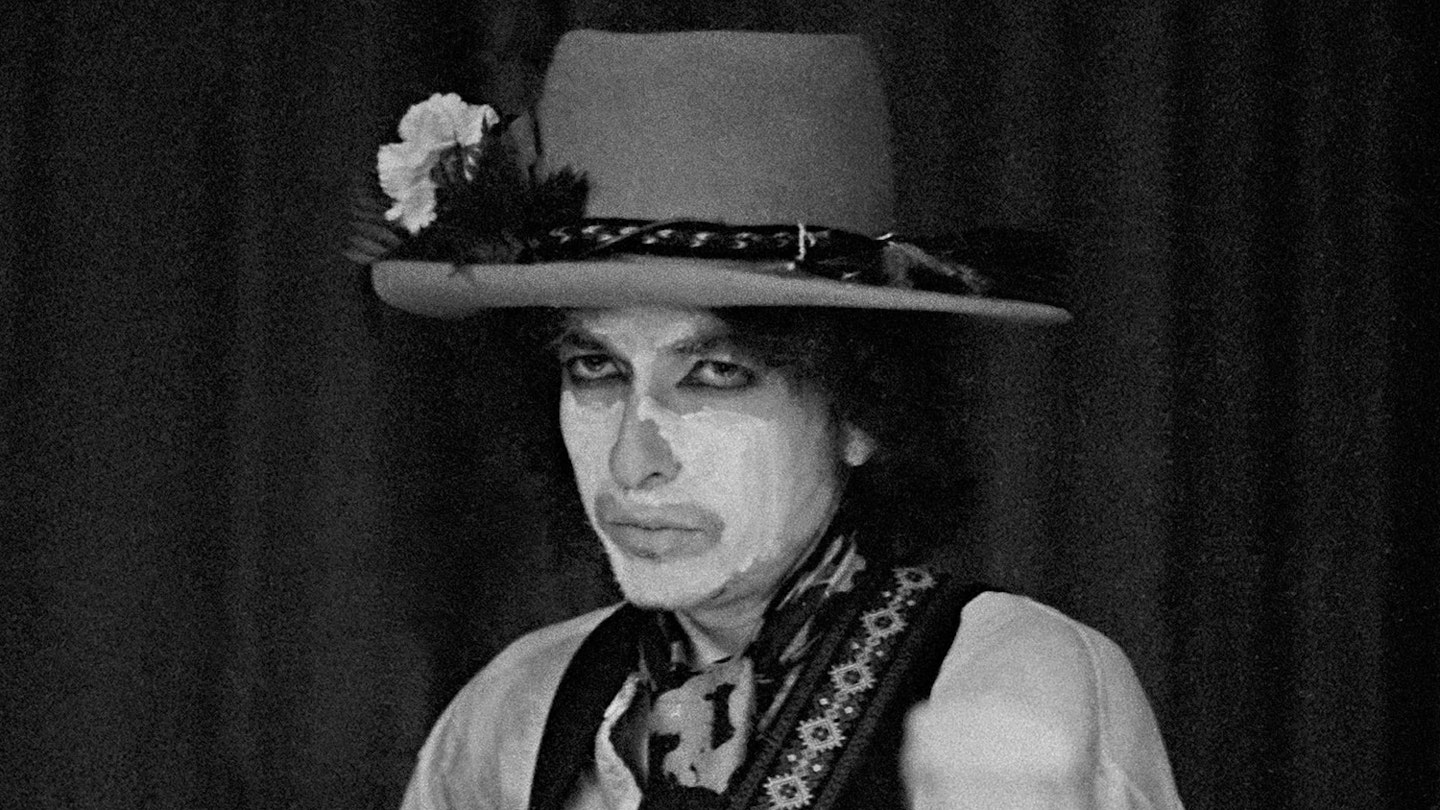

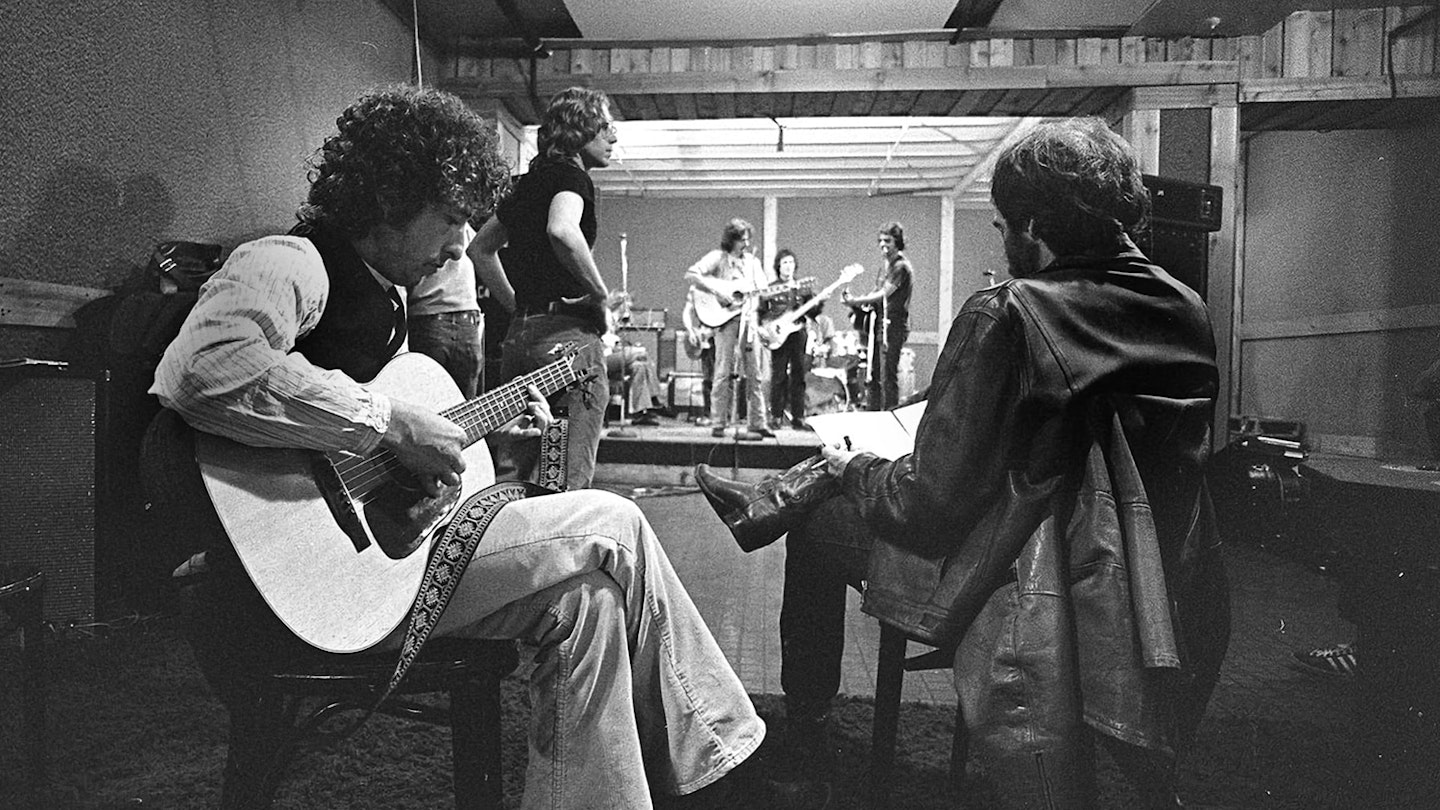

Alongside his career as cinema’s best chronicler of New York underlife, Martin Scorsese has a nifty side hustle as a master Dylanologist. A spiritual sequel to 2005’s No Direction Home, which charted Bob Dylan’s golden years between 1961 and ’66, Rolling Thunder Revue follows the ramshackle 1975-’76 tour featuring music’s biggest stars playing shows in smaller auditoriums in less fashionable cities. But this being Scorsese, it’s more than just an in-concert film. Instead it triples up as a multi-faceted portrait of a creative artist, a prescient portrait of ’70s America in crisis, and a meditation on the nature of documentary itself.

In juggling performances, fly-on-the-wall tour footage, a rare contemporary interview with Dylan and mini profiles of his retinue (poet Allen Ginsberg is a great dancer), the film is overstuffed, but you have to admire the ambition. With the folk scene of the ’60s on its last legs, Dylan’s decision to take a supergroup on the road is partly motivated to show the “true American spirit” during a time of national crisis. Scorsese juxtaposes the backstage antics with footage of Saigon falling, bi-centennial protests, Nixon’s resignation and Ford’s assassination attempt. “Let America be America,” says a voice. “Let it be what it used to be.” It sounds suspiciously like Scorsese’s.

An engaging, self-reflexive effort.

In stunningly scrubbed-up performance footage. Scorsese does full justice to the music, be it ‘Blowin’ In The Wind’ (duet with Joan Baez), ‘Just Like A Woman’ (which Dylan tells a young Sharon Stone was written specifically for her even though it was written ten years before) or a blistering performance of ‘Hurricane’, the song about middleweight boxer Rubin Carter wrongfully imprisoned for murder. Yet the troubadours rarely look happier than in a tour bus covering The Clovers’ ‘Love Potion No. 9’. It is truly joyous.

What Rolling Thunder Revue doesn’t have is a compelling narrative shape — we trot to each venue with no sense of urgency — or on-screen drama (in this regard and this regard only, Dylan is no Luke Goss). But it’s an engaging, self-reflexive effort that has little truck with hagiography or objective truths; the contradictory views of Dylan build up at a dizzying rate. The film opens with a Georges Méliès short, Vanishing Lady, depicting a magic trick, hinting that what follows isn’t all it seems. “I don’t remember a thing about Rolling Thunder,” says Dylan to Scorsese’s camera. Which, along with Scorsese’s absorbing film, is proof he was really there.