Let’s jump straight to the question that is burning a hole in your brain, 14 words in: with 40 minutes of the theatrical version cut (and 42 minutes of new footage added), have the montages – well, okay, one long montage stitched together by a bit of pretty intense acting — survived? Yes, they have! (Some things are worth fighting for! Some feelings never die!)

The message of 1976’s Oscar-winning Rocky was that for some men, for this man Rocky Balboa (Sylvester Stallone), it was enough simply to go the distance. To prove in the ring, and in life, that he wasn’t just a bum (copyright Mickey Goldmill). By the time we reached Rocky IV in 1985, much had changed: Rocky, now World Champion, had moved from the streets to a gated mansion, crease-free sweaters and respectability as part of the poshing-up package deal. The editing and soundtracking had been MTV-ified, with the full-fat franchise chasing the box-office dollars (it remains the most commercially successful Rocky film). And the message? It was clearly trying to, had to, evolve: nine years in, a defeat of Apollo Creed (Carl Weathers) and Clubber Lang (Mr. T) under Rocky’s belt, the stakes had changed. Though to what exactly wasn’t entirely clear: something about getting older, something about being a warrior and something about the Cold War. Oh yeah, and Soviet Russia being dreadful.

The triumph of Stallone’s director’s cut — with a pin-sharp focus on Apollo and Rocky’s relationship and its ruthless removal of anything which distracts — is that it not only nails the central message of the film, but the very point of it existing at all (montages aside).

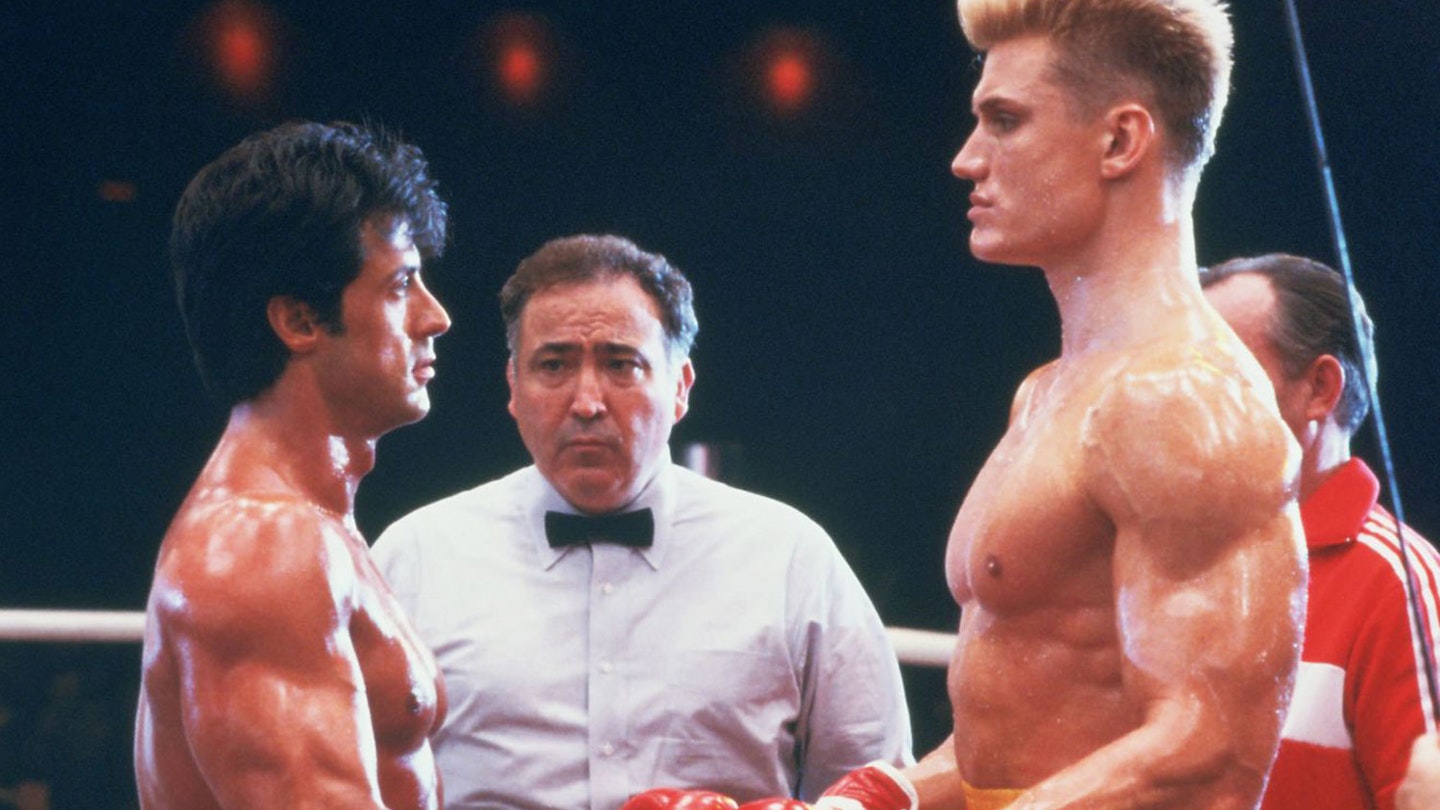

There are traces of it present in the theatrical cut — most notably Apollo’s speech when pleading for Rocky to support him in fighting the newcomer, Dolph Lundgren’s Drago (in a scene that features Stallone’s best writing since the first film: “Without some challenge, without some damn war to fight, then the warriors might as well be dead, Stallion”). With the film’s swelling lanced, the idea of a noble legacy, the warrior’s code, of what it demands, and of who, pushes to the fore. It’s given greater emotional resonance with snatches from Rocky II’s mournful 'Vigil' newly playing behind Apollo’s impassioned dialogue, and then expanded on with a previously unseen two-hander, showing Rocky’s reluctance and Apollo’s need. When Rocky finally agrees to stand in his corner one last time, it’s clearer than ever that he’s complicit in the tragedy that follows in the ring.

It’s a much more sombre context for the film (and goes some way to recontextualising the first three outings) and serves to subdue its worst indulgences. Without the gills of excess breathing quite so hard, the story of Rocky then pledging to fight Drago in Russia on Christmas Day becomes clear: it’s not about solving the Cold War or even a simple revenge yarn wrapped in bombastic patriotism. Rocky needs to find a way to break free of the code. To find a way to change. Apollo couldn’t, it says now more explicitly, and he died because of it.

This thematic precision also demands extra screen time for both Rocky’s wife Adrian (Talia Shire) and Apollo’s trainer and stand-in dad Duke (Tony Burton), both woefully underserved originally. The former voicing frustration at Apollo’s refusal to see any life other than that of a fighter (“Apollo needs to be loved, he just can’t stand to be forgotten. He’s going to have to face up to it and so are you”) and fear that Rocky will suffer the same fate. The latter giving a heartfelt eulogy at Apollo’s funeral (“The warrior has the right to choose his way of life and his way of death”).

Along with Stallone’s writing, the fight scenes were always the heart and pure power of a Rocky film. The choreography and commitment (Stallone claims he nearly died after being punched by Lundgren in IV) writ large on screen. Stallone manages to punch them up (ahem) with extra footage, increased intensity and better sound design. Crucially, Apollo regains a bit of dignity with the deadly Drago fight edited to allow something of a retaliation before he hits the canvas, body twitching.

Along with the robot goes the levity. It’s clearly something the director was willing to sacrifice for a more sedate, character-driven film.

Not everything works — the final victory is now soundtracked by ‘Eye Of The Tiger’ rather than ‘Heart’s On Fire’, leading to a more underwhelming (even if tonally more appropriate) ending; there is a moment of inner monologue that truly should have stayed on the floor of the edit, and somewhat bafflingly, the oiled-up sparring session between Apollo and Rocky that opened the film originally, and showed the combative intimacy of their friendship, didn’t survive (but it is replaced with a new recap of III showing just how crucial Apollo was to Rocky’s survival as a fighter and a man). And then there’s the cruellest cut of all: yep, the robot’s been put out to… do robots go out to pasture? Regardless, along with the robot (Stallone has literally cut out every single scene) goes the levity. It’s clearly something the director was willing to sacrifice for a more sedate, character-driven film. But hell, let’s just say it: Paulie (Burt Young) flirting with a lady robot while his beer-stained vest rides up his hairy gut is missed.

Stallone, though, has re-cut with serious intent (and intent to be serious), and this extends to the ‘enemy’, with the Soviets faring better overall this time around. The full-throttle jingoism is pared back and there’s a litany of favourable edits, some imperceptible to most — such as the moving of a scene with Mrs Drago (Brigitte Nielsen) nonchalantly sparking up a cigarette during the deadly fight to before a punch is landed, rather than when Apollo is bloodied and battered — seeking to round them out as actual human beings.

Drago, who famously had nine whole lines of dialogue in the theatrical version, has a fistful of extra lines and a somewhat over-wrought (and glorious) slow sip of water; this new dialogue (and acting) revealing the fault lines between him and the state that seeks to manipulate — a necessary retconning after the events that Drago shared in Creed II.

Perhaps most interestingly, this new cut of Rocky IV suggests that contrary to what Apollo Creed believed (and lived and died for), the warrior’s code isn’t bound up in patriotism, that it belongs to no one country. Ivan Drago too is a warrior. And in that sense, it belongs to no one man. The responsibility for changing can’t belong to one man. Rocky, the franchise, has always had fascinating things to say about the weight of masculinity — how it’s carried, judged and valued. Now, finally, Rocky IV has found its voice on the matter. Some things are worth waiting for! Some feelings never die!