“Well, if it isn’t the black Bonnie and Clyde,” says tracksuited pimp Uncle Earl (Bokeem Woodbine) midway through Queen & Slim, regarding our two fugitive protagonists with more than a little scenery-chomping relish. It is the sort of line that may as well come with a turn to the camera and a wink; an irresistible, snappy marketing proposition that distils this complex, none-more-2019 project into the sort of arresting pitch that could be scrawled on to a cocktail napkin.

But scratch the surface and it has a more significant resonance. Because just as the real Bonnie and Clyde (a desperate pair of career criminals, hobbled by injuries and actually more prone to rob small grocery stores than banks) have been lost to the more seductive, romanticised 1930s legend, so too do runaways Queen and Slim (respectively, a similarly electric Jodie Turner-Smith and Daniel Kaluuya) find themselves as the baffled, scared recipients of wider public mythologising. In a film that ultimately proves to be about how the world chooses to view you — and how dangerous or powerful that can be — it’s far more than a throwaway gag.

Yes, debut feature director Melina Matsoukas delivers on the promise of a Black Lives Matter spin on Thelma & Louise – replete with stomach-knotting moments of tension, neon-bathed visual razzmatazz and exhilarating musical cues. But Queen & Slim always affords time and space to intimate, quiet moments that orient themselves around these issues of race, perception, legacy and the fledgling love between its two central characters. From a certain angle, it is merely a movie about the most traumatic, life-changing first date imaginable. And it’s all the better for it.

Written by Lena Waithe (the actor and screenwriter perhaps best-known for her Matsoukas-directed, Emmy-winning episode of Master Of None), it opens with Kaluuya and Turner-Smith’s largely unnamed Ohio natives in the midst of a decidedly lacklustre Tinder date at a bright-lit diner (“Did you pick this place because it’s all you could afford?” zings Turner-Smith’s character before Slim shoots back that, no, it’s because “it’s black-owned”).

Tackles urgent, difficult subjects with bravery, care and adrenalised genre cool.

Afterwards, in the wintry slush of an abandoned street, they are pulled over by a white cop (played by alt-country singer Sturgill Simpson) who — as tensions rise — grazes Queen with a bullet. In a powerful, transgressive twist on how these encounters usually go, Slim fires back with the dropped weapon, kills the officer and (prompted by the fact that Turner-Smith’s character is a criminal defence attorney who knows how, well, slim their chances of exoneration are) the two of them hit the road, ultimately bound for Florida and then, hopefully, Cuba.

It’s an opening that perhaps induces some dramatic whiplash. However, from there, as a viral video of the incident casts Queen and Slim as both dangerous criminals and vital avenging angels for a brutalised African-American community, the film settles into an irrepressible groove; visuals, dialogue and performances purring away like the gleaming Pontiac Catalina that Woodbine’s terrific, Louisiana-based relative reluctantly loans our heroes.

Waithe peppers her wry, almost theatrical script with tension-easing comic moments (including a Tarantino-worthy debate about whether Fat Luther Vandross is better than Skinny Luther Vandross) but also artfully reveals Queen and Slim’s divergent character traits in conversations that feel both fiercely personal and like universal disagreements between opposing sides of the modern black American psyche. Matsoukas — who brings a painterly eye and dreamlike cutting from the world of music videos — maintains a curious, agile camera, taking us from flickering juke joints to lush fields that are tended by prisoners who may as well be latter-day slaves.

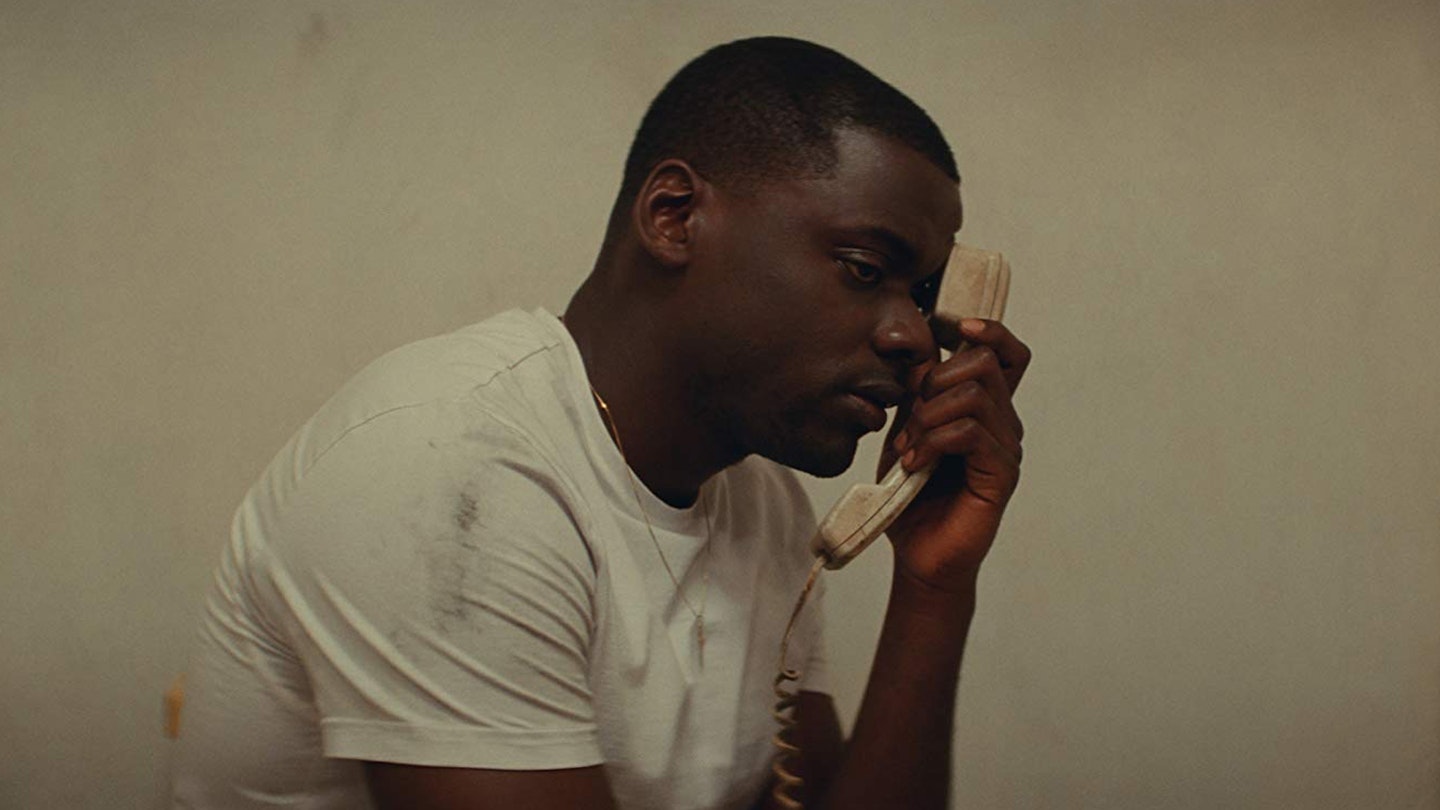

But it’s perhaps the grounded, magnetic lead performances that are most important (especially as the third act throws in a few light implausibilities). Kaluuya, from the moment we see terror and pride swim across his face during that traffic stop, is extraordinarily affecting as god-fearing, slightly gawky Slim. And Turner-Smith (SyFy’s Nightflyers) matches him all the way as Queen: a proud, lonely workaholic who gradually opens herself up to the possibility of love and letting go. If that character progression sounds like the stuff of a Netflix romcom then, in truth, that is sort of the point. Queen & Slim tackles urgent, difficult subjects with bravery, care and adrenalised genre cool. But it triumphs because it shows you the personal toll beyond the politics. And how black lives brimming with potential can still turn on one fateful moment.