Bolstered by her lauded, electric and erotic opus The Piano, Jane Campion’s emboldened adaptation of Henry James’ novel breaks new ground in a myriad of ways. Up until then, James’ beloved fiction about a rich young woman trying to carve out independence against the odds was thought incapable of being adapted for the screen. Campion not only translates the novel into a sumptuous, florid drama that’s committed to the female gaze but also splices it with scenes of her own modern or surreal interpretations of the text: young women swaying like mermaids on land in monochrome, or little mouths painted on white beans, omitting the words “I love you” over and over again.

Jane Campion’s emboldened adaptation of Henry James’ novel breaks new ground in a myriad of ways.

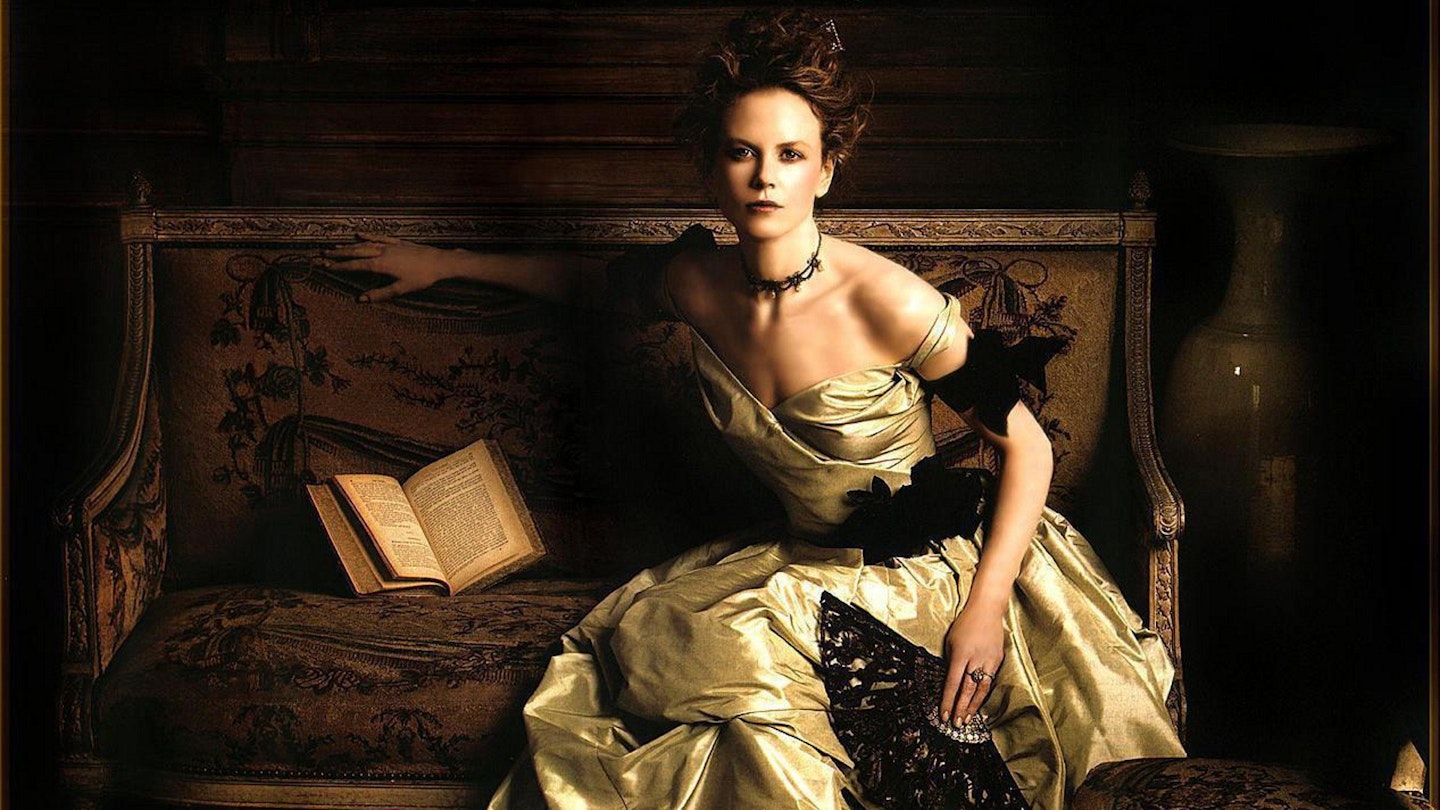

As Isabelle, Kidman plays the paragon of virtue even when her character is at her most vulnerable. Under a nest of unruly chestnut hair, her complexion shimmers between resilience, mottled despair and carnal desire, all illuminated by the bleached wash lighting of Stuart Dryburgh’s cinematography. At her elbow are a stream of suitors, namely Richard E. Grant’s Lord Warburton and Viggo Mortensen’s hungry American Caspar Goodwood. It’s Madame Merle (Barbara Hershey) who bewitches her however and sends Isabelle into the midst of her former lover Gilbert (John Malkovich).

Louche and openly malignant, Gilbert mines Isabelle for her money and gradually manipulates her into near solitude. It’s an unhurried, liquid performance from Malkovich, who glides through a life of opulence while Kidman moves stiffly and carefully in his shadow.

Screenwriter Laura Jones adheres to James’ novel and offers little solace to Isabelle and the audience as our heroine’s world becomes increasingly airless. It’s a startling, lush and disturbingly seductive portrait of how an authoritative woman’s identity can mutate in spite of her status, fortune and desires. At its helm, Campion indulges in The Portrait of a Lady’s baroque setting but delivers something fresh, contemporary and challenging in her framing of Isabelle’s story. Refusing to tie up her journey in a neat bow only makes it more powerful.