Having confounded Sergei Eisenstein during his brief Hollywood sojourn and evaded the best efforts of Josef von Sternberg (in his otherwise admirably restrained 1931 adaptation), Theodore Dreiser's dourly realistic 1925 novel, An American Romance, was given a lustrous makeover by George Stevens in this gothic soap opera. The film's political naivete was reinforced by William Mellor's glossy lighting of Hans Dreier's platitudinous sets, while its dramatic vulgarity was emphasised by Franz Waxman's bombastic score. Yet, somehow, this remains an imposing studio achievement, whose failings are largely subsumed by the director's doughty conviction and impossible beauty of its kissing cousins.

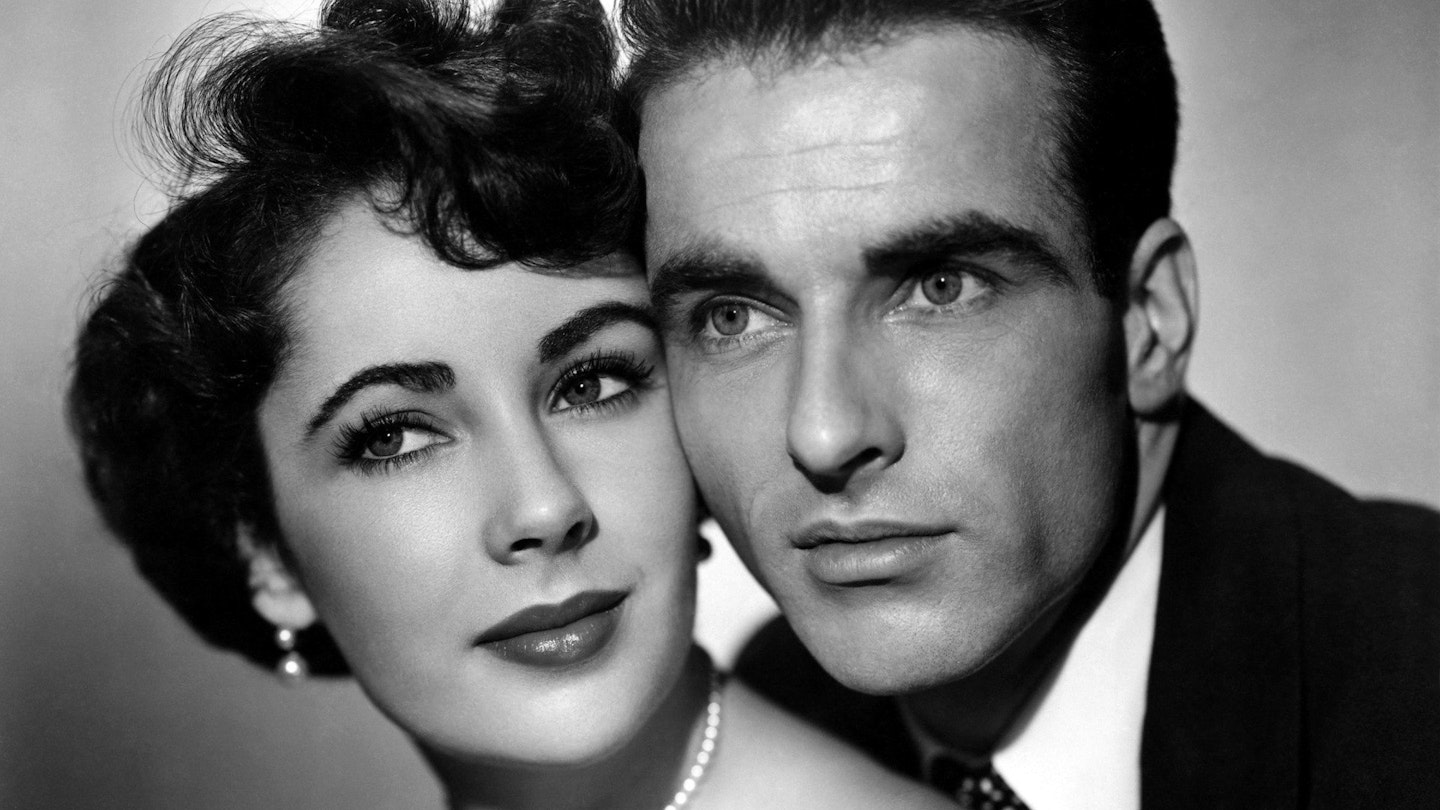

Stevens shifted the emphasis away from George Eastman's ruthless social ambition and downplayed his tawdry relationship with Alice in favour of his idealised romance with Angela. He was fortunate, therefore, that 18 year-old Elizabeth Taylor (who was initially unaware of his homosexuality) fell so hopelessly in love with Montgomery Clift that Stevens was able to capture the intensity of her emotion in scenes that were rewritten to exploit their mutual infatuation.

However, Stevens found Clift a difficult actor to work with, not least because he insisted on taking his motivation from drama coach Mira Rostova, who resisted all attempts to have her ejected from the set. His relations with Shelley Winters were often equally tempestuous. Initially, Stevens had refused to consider her for the role (even ignoring a letter from Norman Mailer), as she had become typecast in glamour roles. However, Winters had convinced him otherwise by showing up for a meeting without make-up and sporting a cheap hairstyle and even less fashionable clothing. But while Winters appreciated the opportunity to discover her character during extensive rehearsals, she eventually came to resent Stevens's hectoring direction and later regreted that her brassy portrayal had saddled her with another stereotype.

Stevens spent two years on A Place in the Sun, which landed six Academy Awards, including Best Director (although he also closely supervised William Hornbeck's editing) and he would repeat the feat with the even more grandiose Giant five years later.