The critical consensus on Roman Polanski's intensely personal Holocaust drama is nigh on universal. Palme D'Or winner, best film at all the major European ceremonies including the BAFTAs, a trio of underdog victories at the Oscars for Polanski, Adrien Brody and screenwriter Ronald Harwood... And proud recipient of two (count 'em, two!) stars in the February (2003) issue of Empire.

For all the august award bodies who seized upon The Pianist with giddy glee 'Important Director Tackles Big Subject Alert! ' it is, in fact, relatively easy to overlook the appeal of what is a disarmingly simple story, shot and structured with lucid transparency.

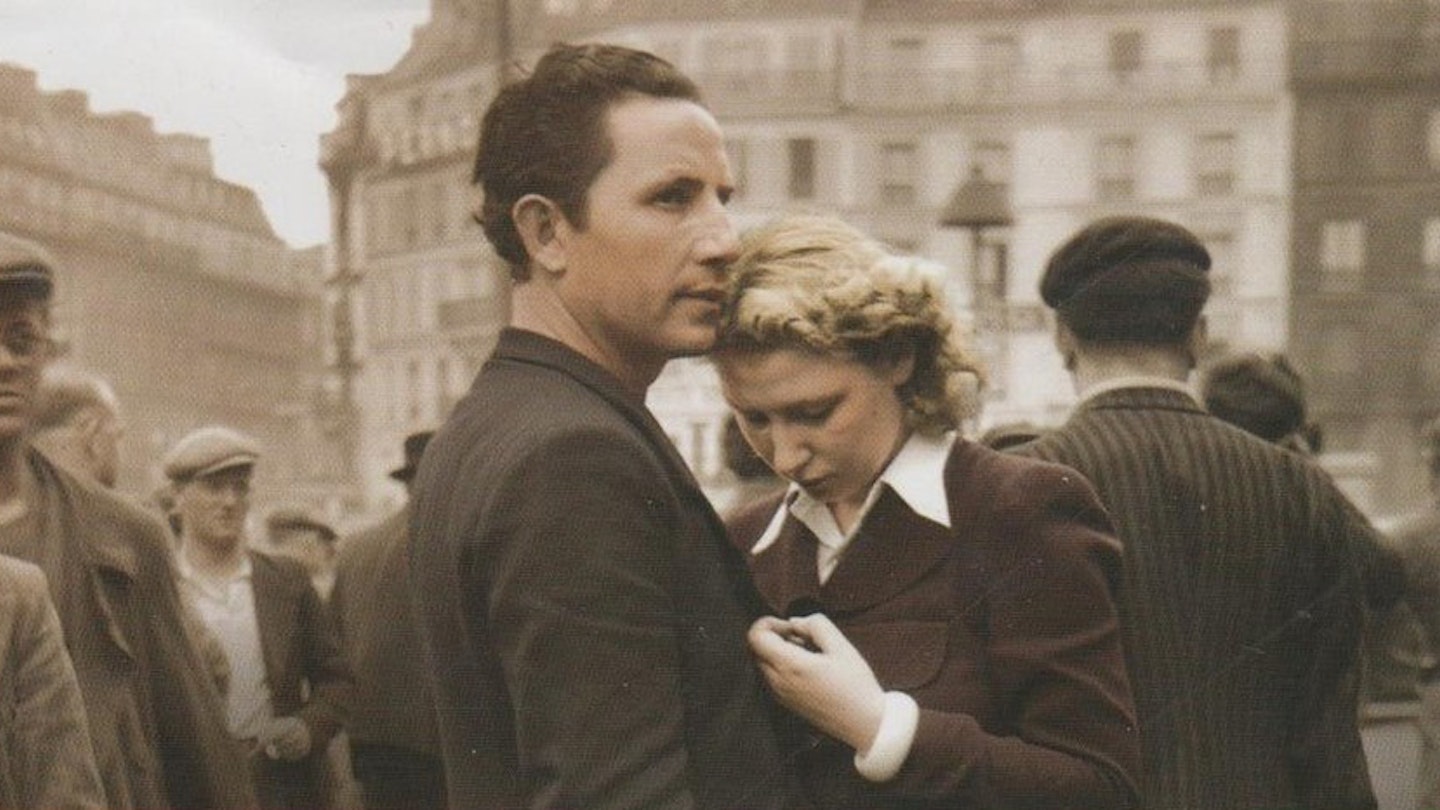

Concert pianist Wladyslaw Szpilman's true-life tale of survival against all odds lacks the broad sweep of, say, Schlindler's List, but benefits enormously from the intimacy and immediacy of an eyewitness account. (Two eyewitnesses in fact, as Polanski himself escaped the Krakow ghetto.)

Where Spielberg set out to capture a large canvas with both economy and Èlan, Polanski's movie is uncluttered by technique and remarkably singular in purpose - supporting characters come and go only as they passed through Szpilman's life.

Naturally, such fidelity to the source material does create its own set of problems. The near-silent third act - Szpilman alone in the ruins of the ghetto - plays like an extended anecdote, a shaggy dog survival story, so to speak.

It is certainly a remarkable yarn, and Brody weighs in with an astonishing physical performance - his gait, his gaze, his very bones aching with hunger - but it is hard to shake the feeling that history is taking place elsewhere. And because this is a survivor's story, The Pianist never quite generates the sheer terror of Schlinder's List, where death could seemingly visit any character, at any time.

There are other niggles if you look for them - pacing is stately to the point of slack in places, and the early scenes of domestic bliss have a very perfunctory feel. But the meat of the story, which covers the creation and destruction of the Warsaw ghetto, is compelling stuff: equal parts absorbing adventure and stomach-churning tragedy.

And it is here, in the margins of Szpilman's story, where Polanski is - and any irony is duly noted - most comfortable, painstakingly recreating the almost incidental daily horrors that he himself lived through. The fact that the director never once caves into easy sentiment or cheap hectoring is almost as amazing as the story itself.