Parallel Mothers is a magic trick courtesy of Pedro Almodóvar. Built on a potentially farcical premise — two women giving birth in hospital at the same time — it is the synthesis of his early, funny ones and later more restrained works, at once a comedy full of plot twists and revelations that build up at a dizzying rate, and a serious, emotionally grounded look at maternal bonds and the draw of family. If it’s not quite top-tier PA, it is built with both flare and precision and, in their eighth film together, emerges as a fantastic showcase for the Pedro Almodóvar-Penélope Cruz dream team.

Cruz is Janis (named after Janis Joplin), a high-end photographer we meet taking pictures of forensic anthropologist Arturo (Israel Elejalde). Janis asks for Arturo’s help in exhuming the mass grave where her grandfather’s body was buried after he was executed by the Falangists in the early days of the Spanish Civil War. At this point it feels like we’re going to get Pedro The Mature of Julieta and Pain And Glory, delivering a coruscating look at how the horrors of Franco’s Spain play out in the present. But then Pedro The Cheeky takes hold and Parallel Mothers becomes something else: a soap opera-infused romp. Janis has quick, breathless sex with Arturo and, revealed by an audacious jump-cut that scythes through acres of exposition, ends up in hospital pregnant with his child. She is sharing a room — obviously Almodóvar manages to get colours popping in a sterile maternity ward — with teen mother Ana (Milena Smit, terrific). The two women become fast friends and decide to swap numbers.

For the Almodóvar faithful, all the tics and touchstones are present and correct.

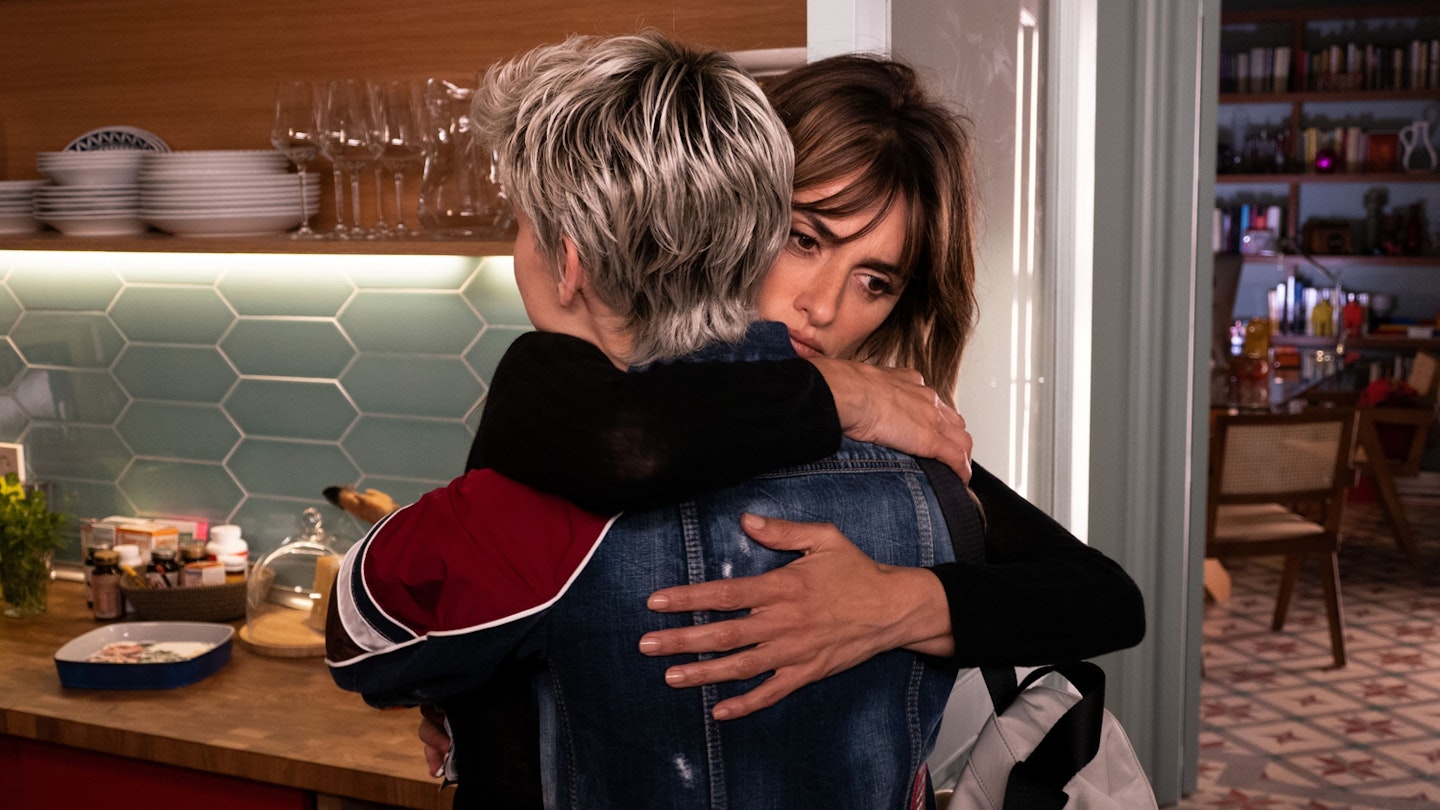

To reveal what happens next is to suck the fun out of Almodóvar’s deceptively light film — suffice it to say the new mothers start to bond as their lives begin to criss-cross in increasingly extreme and complicated ways. For the Almodóvar faithful, all the tics and touchstones are present and correct: a celebration of the strengths and suffering of women; a striking Hitchcockian score by Alberto Iglesias; flawless filmmaking (witness the care and attention lavished on a close-up of a computer mouse), and the welcome return of the director’s stalwart, Rossy de Palma, playing Janis’ agent and confidante. But the jewel in the crown is the Almodóvar-Cruz collaboration. Cruz grounds the potentially ridiculous scenarios with empathy and feeling so that whatever direction the movie goes in, you go with it. Playing a woman holding a secret she is bursting to let out, she is riveting.

The movie’s grip slackens a little in its middle section but, as it enters the final third, Almodóvar, always amongst the most nimble of filmmakers, spirals back to the undertow of the Spanish Civil War, the unmarked grave of Janis’ family standing in for the litany of atrocities committed by Franco’s regime. The director’s conclusion is typical: a group of women, standing in solidarity, drawing strength from the memory of their ancestors.