As Sergeant Bilko, Phil Silvers was given to flattering the pompous by declaring, "in France, they'd build a statue to you." Jerry Lewis, as the whole world is tired of hearing, is the test case of the insanity of the French. In Paris, intellectuals adore the spastic goon character Lewis played in film after film in the 1950s and 60s, taking seriously a performer (and writer-director) only appreciated in his homeland by children and lowbrows. Actually, it's not hard to see why Lewis plays as well in France as Norman Wisdom in Albania. He has never been a witty-lines comedian, though he does universally-translatable funny things with his voice, and his love of the human cartoon sight gag is quite close to the approach of France's own Jacques Tati. In Lewis films, nothing important is said but everything is shown. The Nutty Professor has cartoon jokes like Lewis stretching his arms to the floor by dropping a barbell, but he is also the master of the image that is just funny through very slight exaggeration, like the seat in the dean's office that is just too deep for comfort and seems to swallow Lewis when he sits in it.

A Jerry Lewis film festival would be an endurance test, for he has the traditional clown's failing of wanting to fall down sobbing on his knees and beg for love. The more control he gained over his films after the split with 50s partner Dean Martin, the more given he was to indulging in long periods of laugh-free tastelessness, climaxing in the legendary but unseen concentration camp comedy The Day The Clown Cried (1972) that more or less ended his auteur career. But Lewis has always been the most self-aware, self-critical of screen comedians Chaplin or Stan Laurel wouldn't have accepted the roles in The King Of Comedy (1983) or Funny Bones (1995). There's a creepy sequence in The Bellboy (1960) where Lewis' sweet, mute title character runs into "Jerry Lewis", taking a second role and playing himself as an obnoxious, sadistic bastard. And there's his one truly great movie, The Nutty Professor.

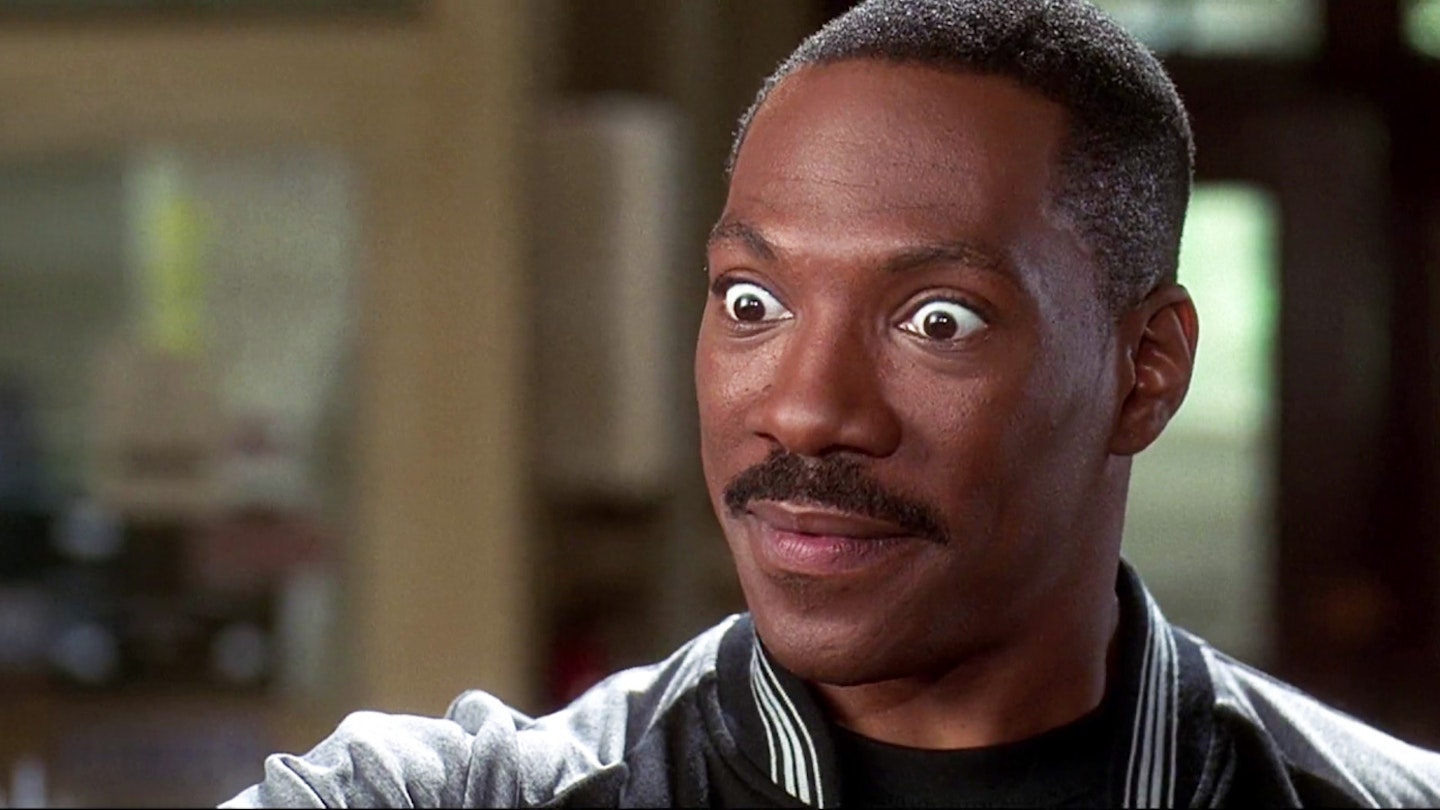

A skit on Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde, this is a film that (as Eddie Murphy discovered) could only be made by someone who wasn't as secure in the affections of the audience as he had been in the previous decade. In 1963, it was read as a strange summation of the Martin-and-Lewis films, with infantile comic Lewis proving he didn't need a smooth straight man because he could play both roles, and the Mr. Hyde figure of swinger "Buddy Love" seen as a nasty caricature of Dino. Actually, Buddy plays more like Martin's Rat Pack padrone, Sinatra, but what Lewis was really doing was presenting his own showbizzy dark side, emerging from the cocoon of his child-pleasing but adult-irritating comic persona.

Americans familiar with Lewis' tireless but also self-serving host duties on the monumentally tasteless fund-raising telethons which make Red Nose Day seem like Remembrance Day, shiver to see in Buddy Love the beginnings of a Jerry Lewis they have come to dread. The Jekyll equivalent, Julius Kelp, is buck-toothed in an ironic nod to Fredric March's 1932 make-up as Mr. Hyde, and speaks with that strangled Lewis whine that makes non-fans want to kill him. He elicits a near-masochistic series of humiliations as Kelp is picked on by the dean, football players, musclemen at a gym and his students, exciting the sympathy only of lovely blonde student Stella Purdy (Stevens). Eddie Murphy's Buddy Love avenges wrongs done to his Sherman Klump, but Lewis' Buddy despises his alter ego and makes a play for Stella in such an unpleasant manner that he becomes just the worst of the series of bullies who have picked on Kelp.

From the wonderfully coloured Expressionist parody of the traditional Jekyll-And-Hyde transformation, in which Kelp turns into a series of ever-more grotesque Hyde types before becoming the "swingingest" Buddy, through to Buddy's rise to power at the local happening place, The Purple Pit, The Nutty Professor is among the most uncomfortable of American comedies. Unlike Stevenson's Jekyll, Kelp learns his lesson, but not before he has had to accept that he has a monster inside him. The finale, in which Love untransforms into Kelp in front of the whole campus, is dead serious, and as devastating as Cliff Robertson's regression to imbecility in the last reel of Charly (1968). It takes a cynical series of gags, with Stella accepting the love of Kelp but keeping bottles of the swinger tonic on hand in case she needs the loving of Love, to take the edge off.