Sam Taylor-Wood’s Nowhere Boy, a biopic of John Lennon, starts with Lennon running past the columns of the Liverpool Concert Hall as the jangling chord — put simplistically, it’s F with a G on top — that opens A Hard Day’s Night rings out. It’s a witty, arresting opening, redolent of nascent genius, and the one and only time we hear The Beatles in the entire film. For Taylor-Wood’s well-acted, well-mounted portrait concentrates on the young man’s formation, not the established mythos. It may not be 100 per cent absorbing — early scenes lack incident — but is always entertaining, keeping a clear-eyed view of a musical great.

More Douglas Sirk than Walk The Line or Ray, Nowhere Boy is a tug-of-love melodrama, with Lennon bouncing between restrictive guardian Aunt Mimi and liberated biological mother Julia. Kristin Scott Thomas, chain-smoking for England, can do this kind of icy matriarch in her sleep, but suggests depths of affection for John beneath the glacial veneer. Much more interesting is Lennon’s relationship with Julia, the woman who introduced him to rock ’n’ roll and the idea of musical creativity by teaching him banjo and giving him a harmonica. Anne-Marie Duff gives Julia an engaging unconventionality and vivacity, even suggesting an undercurrent of sexual attraction to her estranged son (“Rock ’n’ roll actually means sex,” she tells him as they dance together). The reason why Lennon is living with his aunt is hinted at throughout the film, a mystery that gives the film its dramatic kick. When it comes, Nowhere Boy truly ignites for the first time.

Taylor-Wood sketches Lennon’s teen rebellion — he bunks off school, rides atop double-decker buses, fingers girls in the park, shapes an Elvis-style quiff — and his gradual gravitation towards music. Matt Greenhaigh’s script (he also wrote Joy Division flick Control) contains portents of things to come — John strolls past Strawberry Fields children’s home, doodles a walrus in an exercise book and is turned away from The Cavern Club— but thankfully the nods and winks are kept to a minimum. The first meetings with both a baby-faced Paul McCartney (Thomas Sangster) and George Harrison (Sam Bell) are handled without pomp, McCartney simply asking for tea, Harrison casually introduced on a bus.

Working with cinematographer Seamus McGarvey, Taylor-Wood gives ’50s Liverpool a vibrant feel that is aeons away from the clichéd grit and grime of archive Merseyside footage. But, considering Taylor-Wood’s position within the Young British Artists clique of the mid-’90s, Nowhere Boy plays it surprisingly safe, cinematically. The filmmaking is always assured, but perhaps Lennon’s originality should have been reflected by a more raw, rebellious approach.

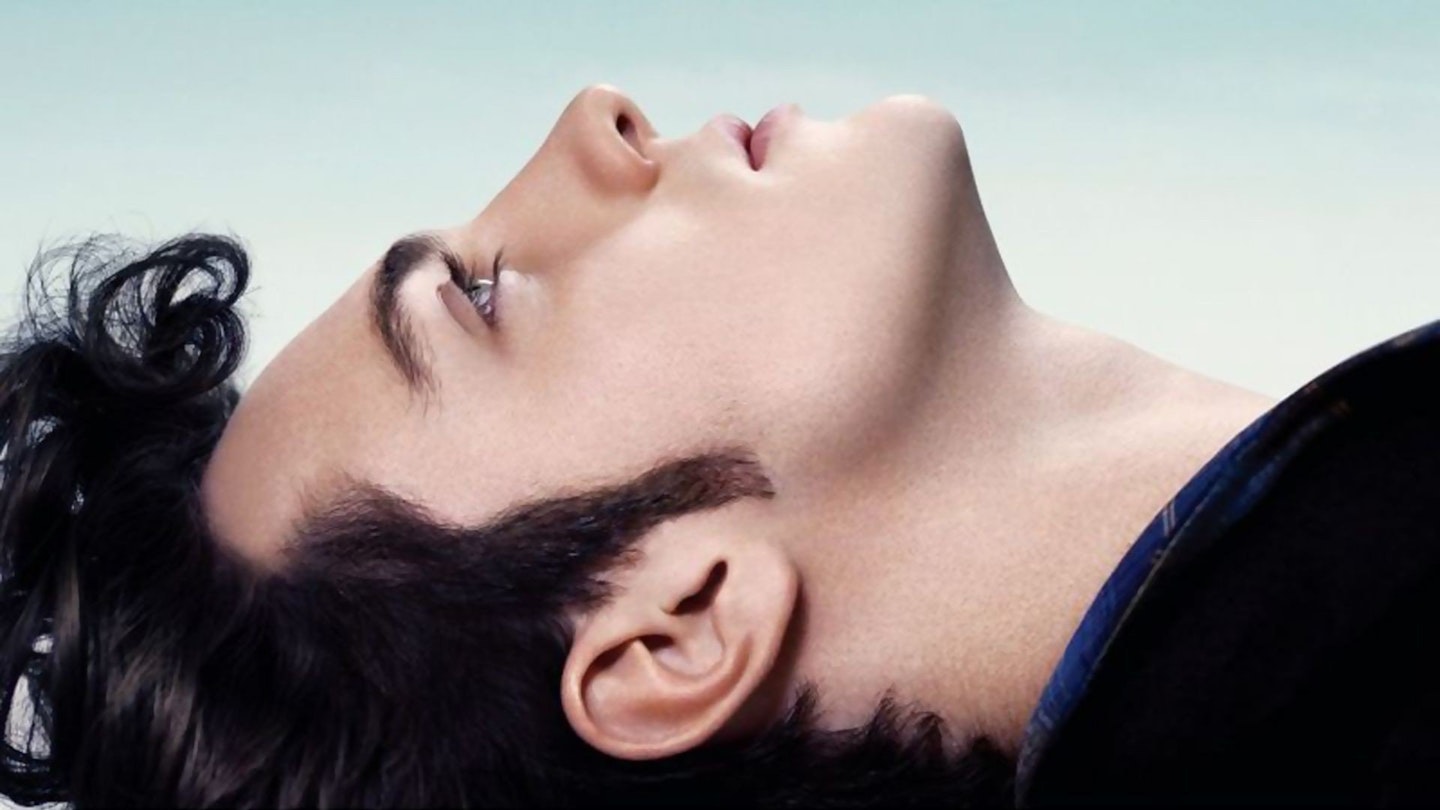

This spirit, though, is happily alive and well in Aaron Johnson. His Lennon is by turns feral, vulnerable, quick-witted and callow, never able to grasp the depths of love both women hold for him. Next year’s Kick-Ass may make Johnson a star, but Nowhere Boy feels like we are glimpsing a major talent in waiting. Which is pretty apt, really.

.jpg?ar=16%3A9&fit=crop&crop=top&auto=format&w=1440&q=80)