Made in 1968 on a hand‑to‑mouth budget by enthusiasts in Pittsburgh, this suitably grungy off‑Hollywood production became one of the most influential horror movies ever made.

George A. Romero’s film has had official sequels (Dawn of the Dead, Day of the Dead, Land of the Dead), remakes (one in 3-D), parodies (Return of the living Dead, Shaun of the Dead), rip-offs (Living Dead at the Manchester Morgue) and several horribly mutilated re-releases with useless extra footage, new soundtracks or colorisation. It changed the face of the horror film, setting a precedent for the work of directors like Tobe Hooper, Wes Craven, John Carpenter and David Cronenberg in the 1970s.

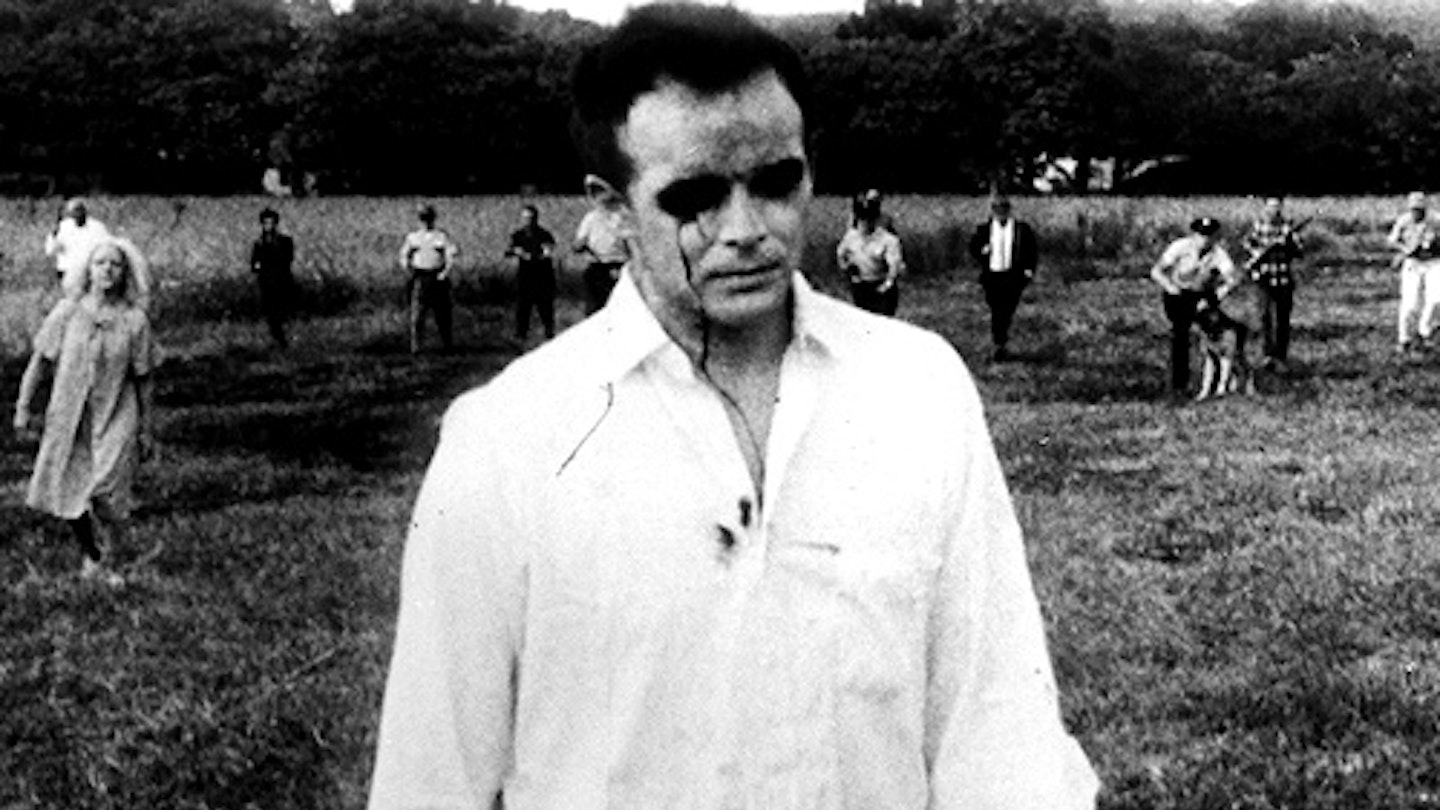

In fact, it’s such an important movie that it runs the risk of disappointing first-time viewers who’ve seen all the later films that copied its licks – part of its strength is that it’s not a glossy, predictable Hollywood horror and so it has a grainy, semi-amateur, black and white look which gives it a dread sense of conviction. The shambling dead besiege a group of squabbling wannabe survivors in an isolated farmhouse, eating the entrails of those too inept to see them off with a bullet to the brain.

Many of its plot strands were unprecedented: a heroine who reacts credibly to an appalling situation by becoming a useless catatonic, a black hero who finally has less to fear from the zombies than from the ghoul-hunting posse combing the countryside as if on a Vietnam search and destroy mission, news bulletins that include expert advice (‘kill the brain and you kill the ghoul’) from the men on the ground, a relentlessly pessimistic ending.