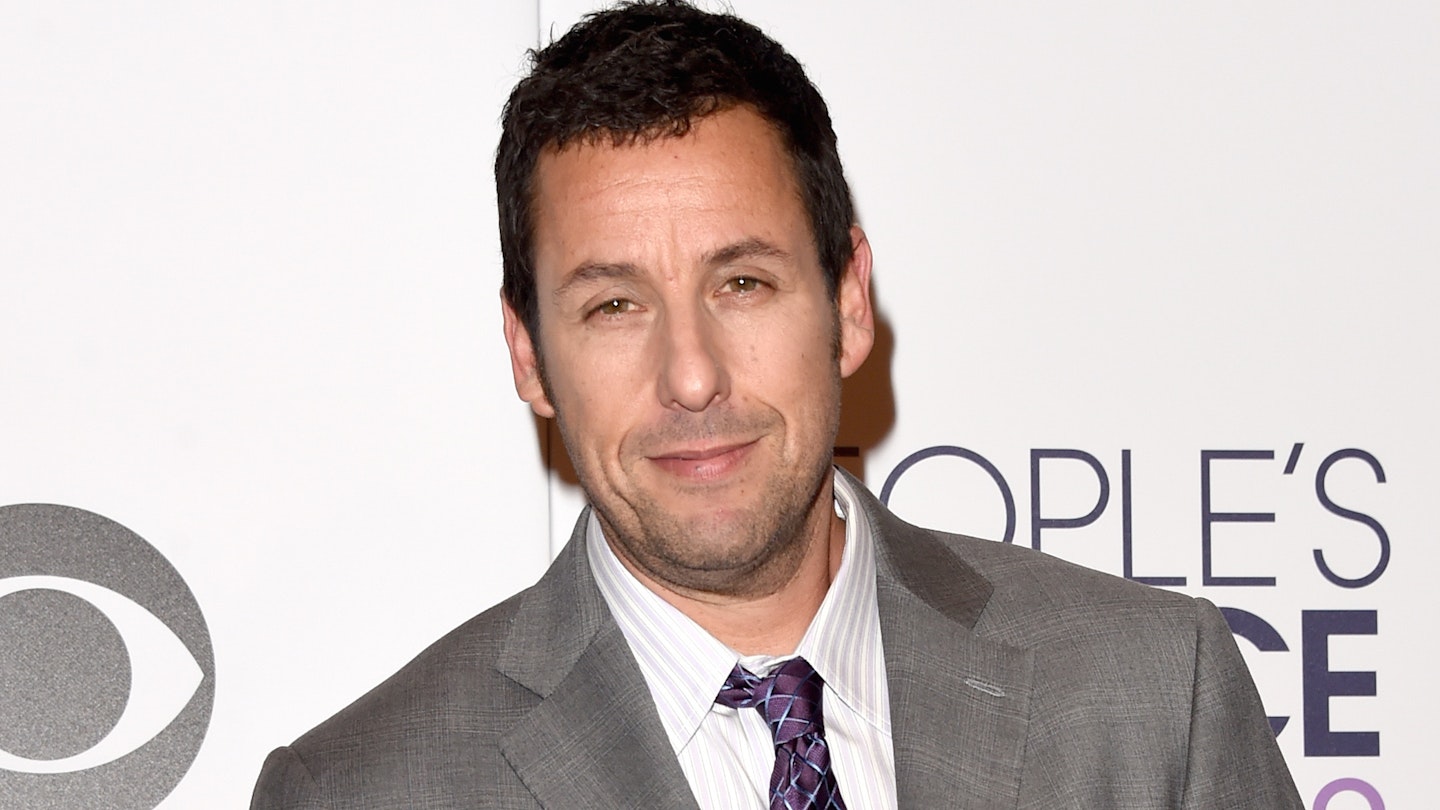

Broadly speaking, there are two types of Adam Sandler fans: those who love his dramatic chops in Punch-Drunk Love or Funny People, and those who’d just as soon see him trying to knock seven bells out of Bob Barker in Happy Gilmore or sing-choking his way through Madonna’s Holiday in The Wedding Singer.

A deep dive into the neuroses of grown-ups who’ve never quite grown up.

With the blue-collar Schmoe roles of that second category often missing the mark of late, The Meyerowitz Stories comes as a handy reminder of what he can do. And, as Noah Baumbach’s wordy, wry slice of New York bohemia proves, he can do both. His turn as Danny, a doting dad and struggling, unemployed son in a family obsessed with achievement, is up there with his best. There’s even a spectacularly hapless Sandler fist fight for the Happy Gilmore aficionados out there.

His starriest ensemble, Baumbach has assembled a cast skilled in the specific tone of bruisingly intimate dramatic-comedy he’s been striking since 2005’s The Squid And The Whale. Sandler’s Happy Gilmore alumnus Ben Stiller (returning for a third Baumbach collaboration), Dustin Hoffman and Emma Thompson could draw laughs from a train timetable and bring poignancy to the most throwaway gags. The machine-gun patter of Baumbach’s dense script (dialogue arriving at a million miles an hour, it often feels like the screenplay must have taken two people to lift) offers them all sorts of opportunities to show that off, as it ruminates on the cracks and complexities of life in a family of high-maintenance Jewish New Yorkers.

Returning to his own spin on the Anna Karenina principle — every unhappy family in a Baumbach film is unhappy in all sorts of hilariously dysfunctional ways — Meyerowitz orbits around Hoffman’s abstracted, self-centred patriarch, Harold. He’s the kind of man who’ll chuck a tantrum because he feels his art has been neglected, while remaining completely oblivious to his own damaged kids. He’d be totally insufferable if he weren’t often laceratingly funny (“$35 for a salmon?” he bellows at a family dinner. “Do you get the salmon to blow you for that?”), and imbued with a strangely childlike charm by Hoffman. In one of the film’s funniest scenes, he becomes so bitter witnessing an artist peer’s successful MoMA show that he literally runs away. Forget Marathon Man — here’s Marathon Man-child.

The stories — the film is broken into three chaptered parts — major on the kids, however. Danny and his half-brother Matthew (Ben Stiller), now living in LA as a successful accountant, have little in common bar unresolved anger at their emotionally absent dad. Danny’s gentle bond with his daughter (Grace Van Patten) as she prepares for college is the one good thing in his life, as circumstances drive him back under his father’s roof. For Matthew, those old wounds are exacerbated by the discovery that Harold’s often sozzled new partner (Emma Thompson, having a total blast) wants to sell his boyhood home. This psychological tinderbox has a thousand possible sparks, but when one does come it floors them all in surprising ways. Everyone gets their volcanic moment, even owlish, diffident sister Jean (Elizabeth Marvel), as the family comes together and breaks apart in swells of repressed anger.

There are obvious parallels with The Royal Tenenbaums, not least in Stiller’s presence as the family’s insecure scion, but Baumbach’s film is a less whimsical beast than Wes Anderson’s, its characters’ wounds more real and relatable. He’s crafted a deep dive into the neuroses of grown-ups who’ve never quite grown up.