Inspired by André Devigny's account in Le Figaro Littéraire of his own escape from the notorious Montluc jail in Lyon, this is the first of Robert Bresson's three prison pictures and, like Pickpocket and The Trial of Joan of Arc, it is as much about Catholicism as it is crime and punishment - hence, the opening caption citing Jesus's words to Nicodemus, `The wind bloweth where it listeth'.

However, this was followed by the statement, `This is a true story. I have told it with no embelleshments.' Bresson certainly insisted on complete authenticity and Devigny not only served as an adviser on the Montluc set, but he also loaned the director the ropes and hooks he had used in his escape. But this is, nevertheless, a film whose spiritual realism was controlled to the minutest detail.

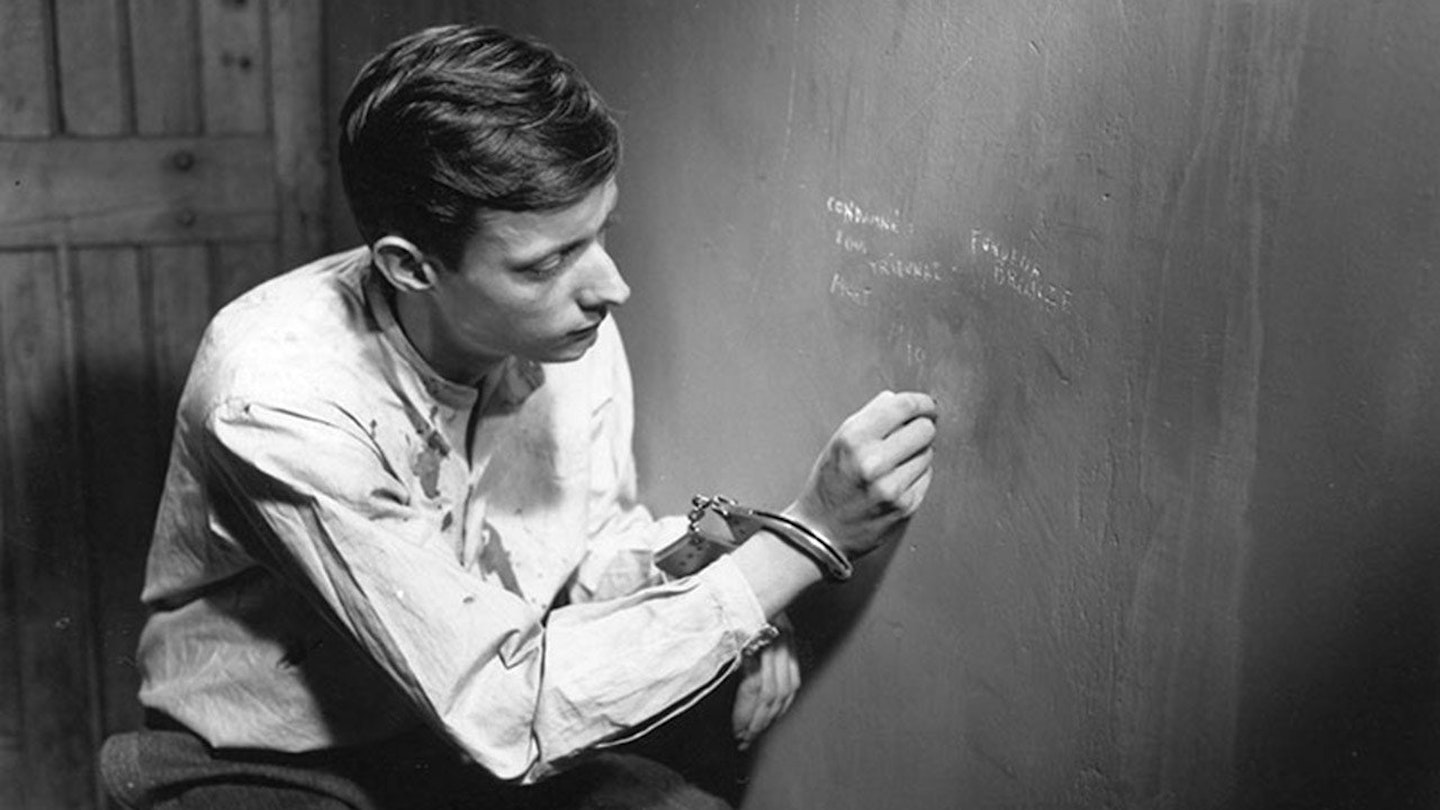

Bresson's screenplay was confined to a series of elliptical episodes that reduced Sorbonne student François Leterrier to a model whose performance was wholly dictated by Bresson, to the extent that he almost played Fontaine himself via a primitive process of real-life motion capture. Yet the prisoner was virtually stripped of his personality, as his manual dexterity mattered more than any gesture or expression. He was, therefore, presented as an empty vessel for the will of the unseen power that guided his hand and this sense of divine intervention was reinforced by the arrival of Jost, as Fontaine initially considered killing him as a spy, only for him to prove crucial to the escape's success.

Making for fascinating contrast with both Jean Renoir 's POW picture La Grande Illusion and Jules Dassin's heist classic, Rififi, this is a compellingly tense tale, even though we already know the outcome. Bresson's use of the claustrophobic setting and the alternately terrifying and tantalising sounds of incarceration and liberaty is masterly. No wonder Jean-Luc Godard opined after seeing the film, that Bresson was `to French cinema what Mozart is to German music and Dostoevsky is to Russian literature'.