In the early 1980s, two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning African playwright August Wilson began writing a collection of ten plays known as the ‘Century Cycle’, with each work telling a story about the Black American experience in a different decade. Fences was the first of these plays to get given the theatrical treatment in 2016, courtesy of director and star Denzel Washington, to whom Wilson’s plays have been entrusted. In many ways Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom’s strengths are similar to Fences, with the strong material and emotionally raw performances winning the day even when the transition from play to film isn’t so seamless.

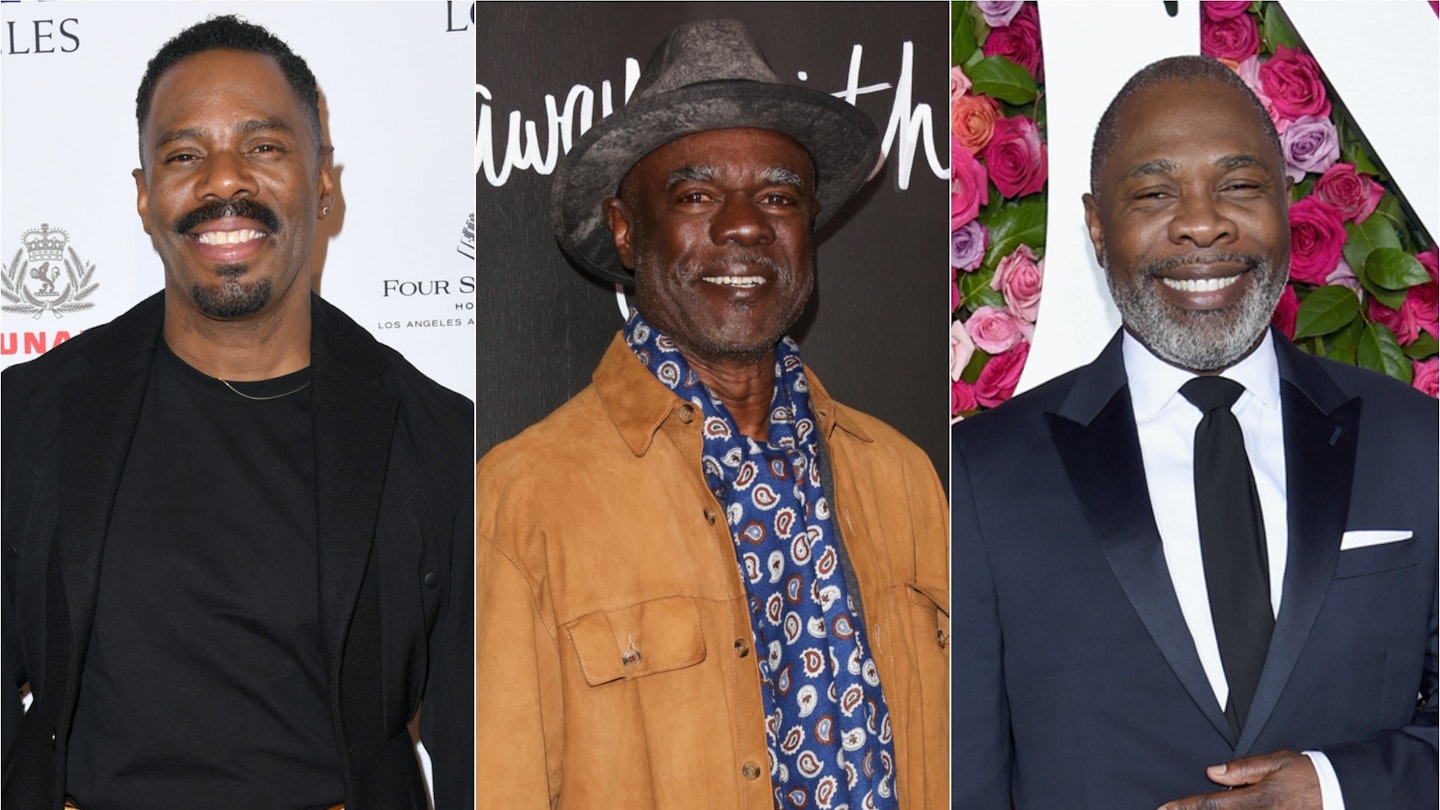

It takes Ma (Viola Davis) almost 20 minutes of screen time to arrive at the recording session where much of Black Bottom takes place. Before then we meet her band — which includes Toledo (Glynn Turman), Slow Drag (Michael Potts), and religious band-leader Cutler (Colman Domingo) — before the camera eventually finds Levee (Chadwick Boseman), fresh from the purchase of some ostentatious yellow shoes. The banter between these four men early on immediately establishes a winsome dynamic between three wise old heads and their younger and cockier upstart. It allows them to go from cracking jokes on each other’s fashion sense to heavily philosophical discussions on a dime, and they do.

It’s in those discussions where the timelessness of Wilson’s writing, adapted for the screen by Ruben Santiago-Hudson, really shines through. Navigating an entertainment system that’s rigged against people of colour, ownership over one’s art, and knowing your worth are all things that Black artists still grapple with today.

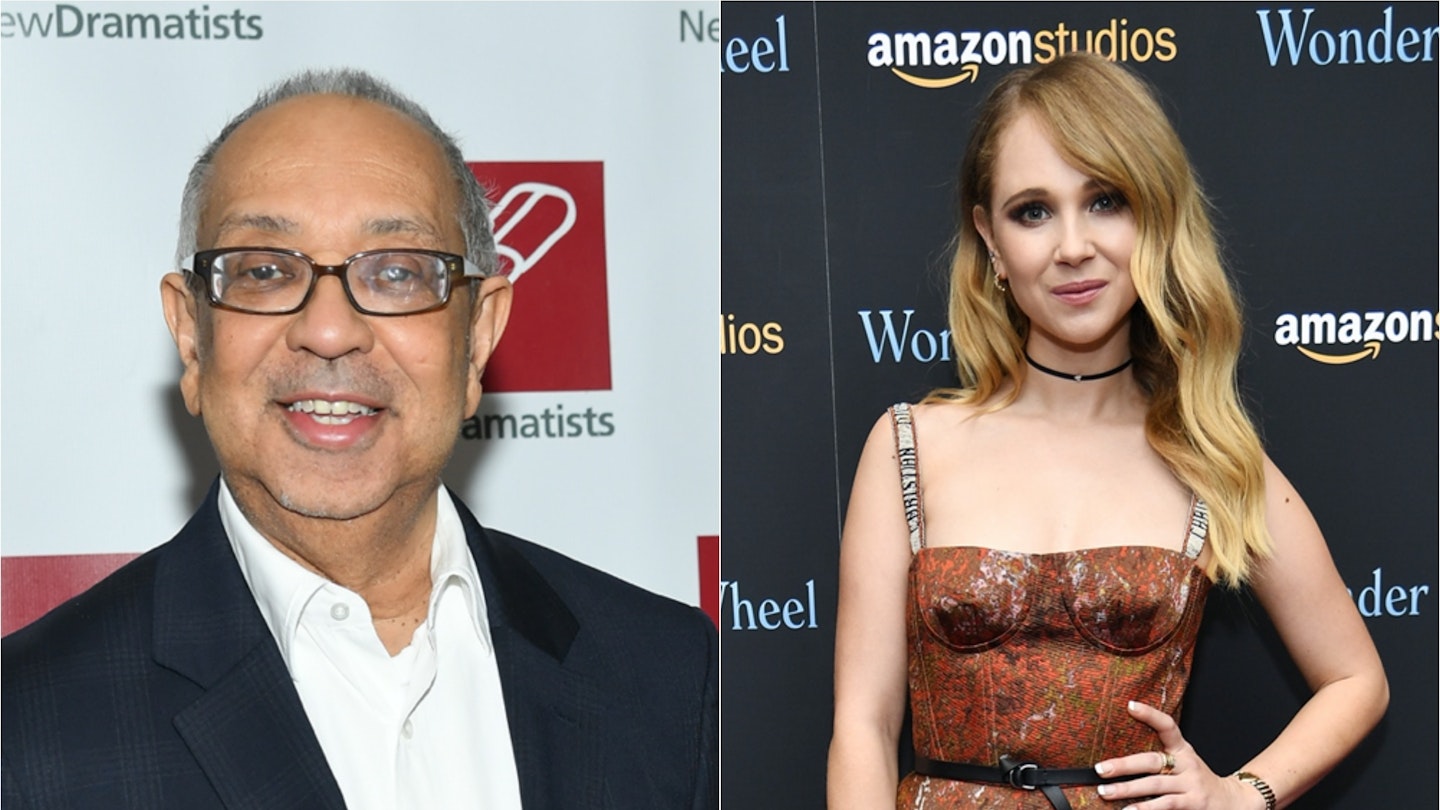

Washington called the shots on Fences, but for Black Bottom he sought out George C. Wolfe. On paper, it makes sense: in addition to being a mega Wilson fan, Wolfe has had award-winning success directing plays on Broadway. The results here, however, are a bit of a mixed bag. He does a good job of drawing you into the film’s sweat-slicked world (the play takes place in the winter, the film takes place in the summer), and a fun mini-montage mid-movie is one of the few ways the language of film augments the storytelling. But too often Black Bottom feels overly play-like, never more so than when Turman’s Toledo delivers his ‘African Stew’ speech about white exploitation. Taken in and of itself it’s powerful, but its placement in the movie is inelegant and it ends up feeling a touch heavy-handed.

It’s simultaneously thrilling and sad to watch Boseman in action here.

Thankfully, as screen and stage legend James Earl Jones once said, “It’s hard for an actor to go wrong if he’s true to the words that August has written,” and everyone rises to the material admirably to tap into the force of Wilson’s words. Davis is especially noteworthy: Ma’s fearless demeanour demanded an equally fearless performance, and in her hands the titular songstress is entertainingly unapologetic, whether she’s reminding everyone in her orbit who’s in charge, or seducing her female lover Dussie Mae (Taylour Paige). From Ma’s ostentatious appearance — Davis put on 20 lb for the role, and Ma often wears a full face of make-up and even a set of gold teeth — to the swaggering dialogue, Davis completely disappears into her larger-than-life character.

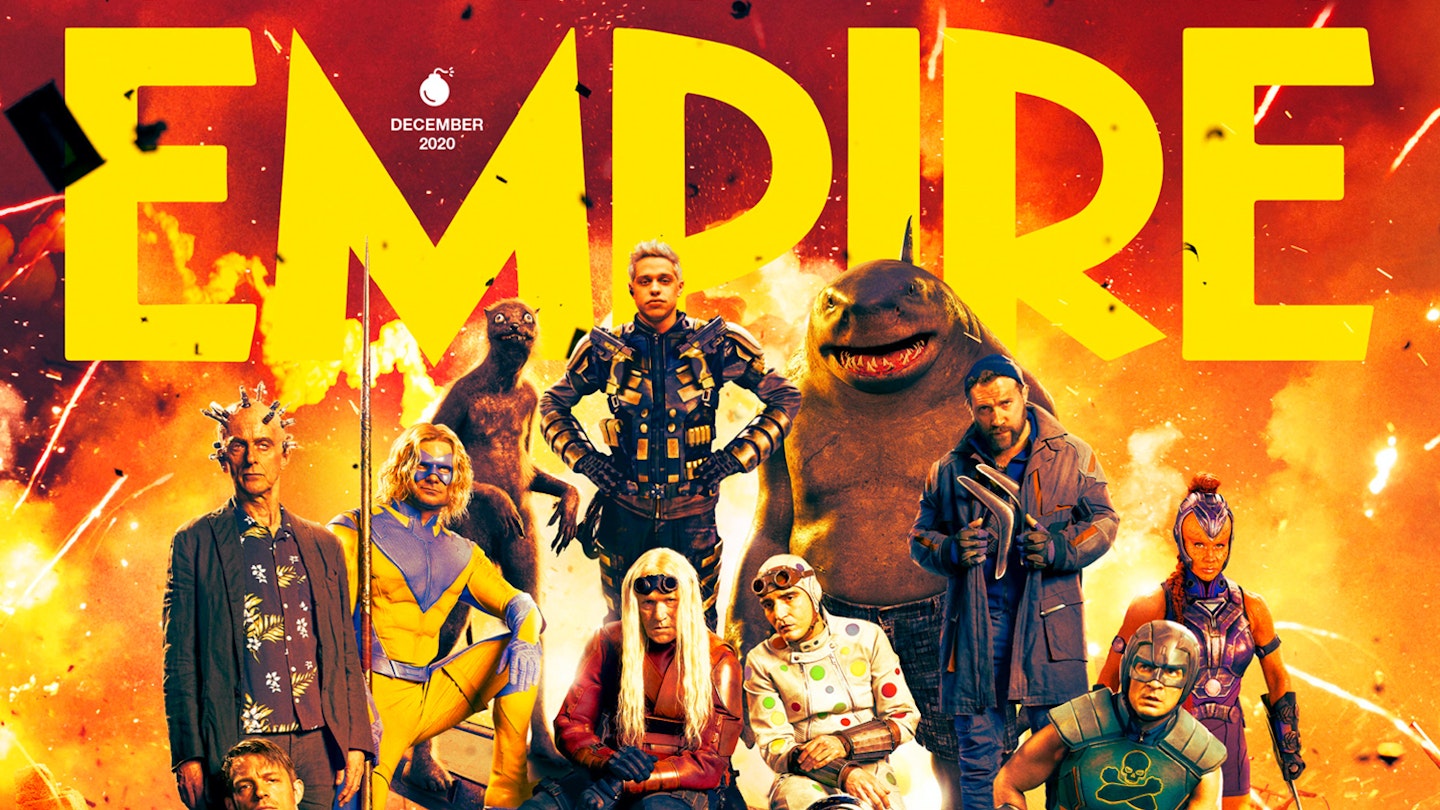

And then there’s Boseman. His Levee always seems to have a glint in his eye, so sure is he of himself and his future stardom, and Boseman marries the high-energy flamboyance he brought to playing James Brown in Get On Up with the soulfulness he brought to the MCU’s T’Challa and so many others. It all comes to a head in two searing monologues in which Levee rages at God — a rare sight for a Black man on screen, making it all the more visceral — and Boseman empties the clip in both scenes, eking out every drop of emotion. It’s the finest performance of a career that ended way too soon earlier this year, and it’s simultaneously thrilling and sad to watch him in action here.

It is, however, somewhat fitting that Boseman’s final bow is in an adaptation of an August Wilson play. A fan of the playwright since he was ten, in 2013 he wrote, “For the songs, rituals and folklore that were lost in slavery’s middle passage, [Wilson’s] plays are those forgotten songs remixed for the struggles of adapting to these shores.” With the world in the midst of a racial reckoning, there’s no better time for Wilson’s plays to once again be remixed for the big screen. On this evidence, we should all be looking forward to seeing more.