When two versions of the same man sit in a diner discussing time travel paradoxes, it’s almost a relief that the older (not necessarily wiser) incarnation tries to change the subject — claiming that talking too much about this stuff makes your head hurt and they’ll only end up drawing diagrams on the table. Of course, one point of this scene is to admit that we’ve been here before and will most likely pass this way again. Headache-inducing paradoxes have been a part of the time travel sub-genre of science-fiction ever since Mark Twain and H. G. Wells first set out to close the loop (here a synonym for a combination of murder and suicide) and the movies have evolved a complicated visual language for depicting the process of history being rewritten.

An early, crucial sequence of Looper shows an old man (Frank Brennan) on the run while his younger self (Paul Dano) is being tortured — suddenly, his past is altered so that messages appear written on his arm in long-healed scars, and his fingers, facial features and limbs disappear as his memory is rewritten to give him a life of 30 years as a mangled basket case. Otherwise, narration sets up the premise and nudges you not to ask too many questions. Like recent, clunkier S-F action films Repo Men, Surrogates and In Time, a whole noirish society is built around one new tech trick and we just have to accept it to get into the chase flow.

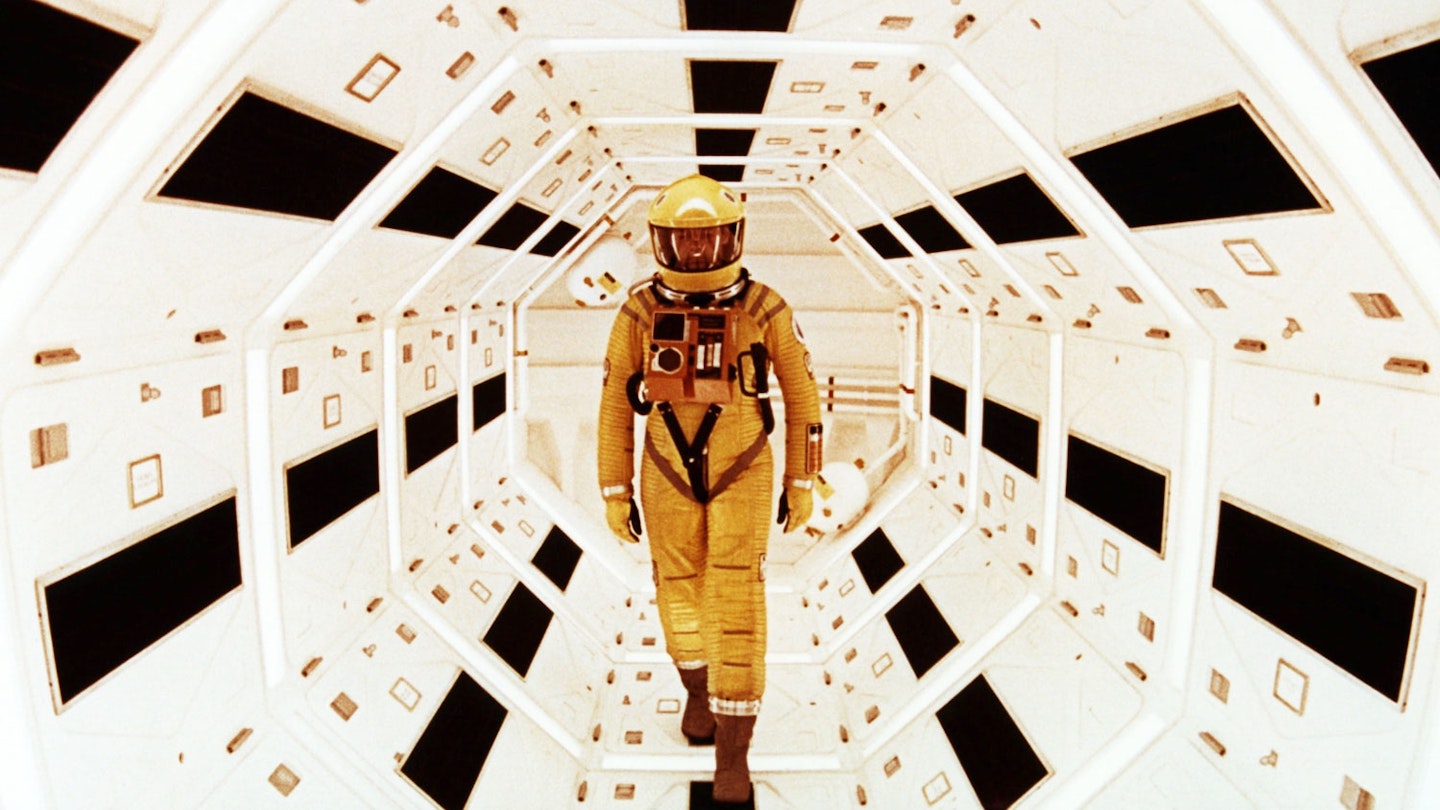

The title might even be a conscious echo of Michael Crichton’s Looker, an early example of single-issue dystopian cinema, and Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s presence carries over from the one recent unassailable triumph of the form, Inception. Surely, even in a society run by CSI HAL — the justification for time travel as an alternative to dropping a corpse off the East Pier with feet in a bucket of concrete — there are easier ways of getting rid of a disappointing associate than zapping them into the past to be gunned down at the edge of a cornfield which has the same purpose as the forest glade in Miller’s Crossing? Also, a sociopathic master crook with a monopoly on time travel tech should have more ambitious ways to mess with history than this, especially when the mysterious Rainmaker — crime boss of the future’s future — seems to have no qualms about dickering with the space-time continuum in the way most S-F franchises are sniffy about.

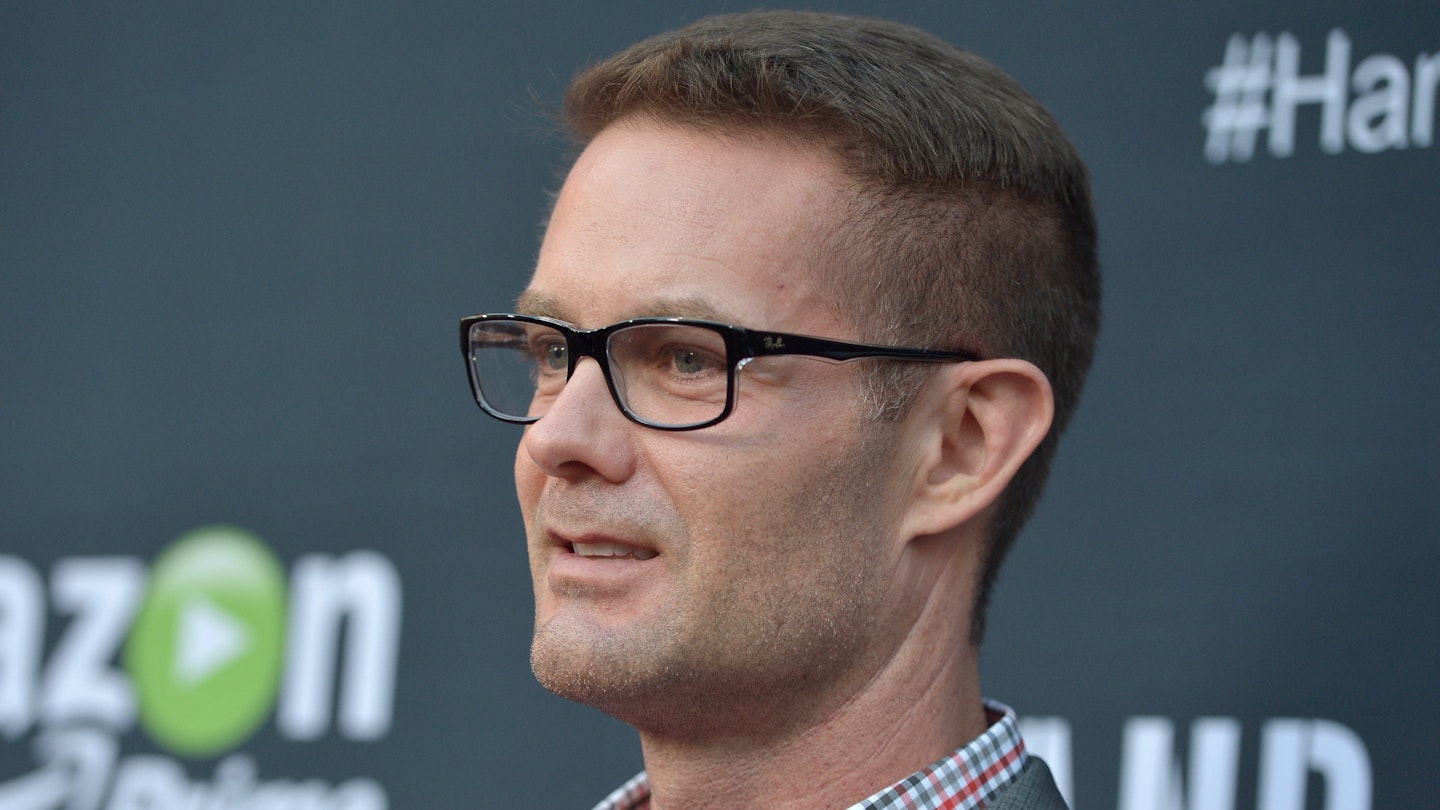

Those quibbles are literally beside the point, which is — despite a level of plot complication that a degree in quantum physics won’t help you sort out — a simple, emotional truth. If you could go back in time and tell your younger self where he was going wrong, the kid still wouldn’t listen to you. And if you saw how badly things were going to turn out, you’d probably just make them worse. With the high-school noir Brick and the con-man triangle drama The Brothers Bloom, writer-director Rian Johnson established himself as a distinctive voice in mid-budget coffee house cinema, the sort whose projects offer the kind of well-written roles that persuade established actors to take pay-cuts to take part. Here, he’s up a level, delivering a post-economic collapse dystopia with an interesting city/country divide which harks back to the Depression (the heroine has to defend her homestead against marauding hobos who’ve failed to make the cut in the big city), and gets to do comic-book action sequences with hover-bikes, oversized guns (the brutal, retro weaponry is nicely designed) and Akira-like telekinetic prodigies.

But it’s still crackling dialogue and unusual characterisations which hold the interest in a genre where those qualities are too often deemed superfluous. Looper connects where, say, Surrogates missed because it feels as if its world has been thought out properly, but also its characters make sense as inhabitants of it — the protagonist is a gangland killer hooked on an eye-drop drug (a nod to that semi-forgotten dystopia Harley Davidson And The Marlboro Man?) because of the way he was brought up in hard times and found a father/family substitute in the gang run by a refugee from the future (Jeff Daniels) whose tips (“learn Mandarin”) he ignores as he clings to nostalgic retro items like red vinyl records.

Joseph Gordon-Levitt has to put up with an effects make-over which turns him into an acceptable young Bruce Willis, to avoid the Young Emma Thompson-didn’t-look-like Alice Eve complaint some made about Men In Black III. He also does a creditable job of not imitating the Bruce of Moonlighting or Die Hard but depicting the kind of callous, incipiently sensitive young gunman who might grow up to be the battered baldie Willis now plays. It’s an irony that if you had time travel and could cast young Bruce Willis in this, you’d still give the role to Gordon-Levitt, whose collaboration with Johnson (after starring in Brick he had a bit part in The Brothers Bloom) is becoming a regular and noteworthy teaming. A 30-year montage shows how one Joe turns into the other in a hard life on the run, with a redemptive late-in-the-day romance, but the circumstances of the story which brings them together invalidates all this, so young Joe has to fast-forward through the tough lessons and emotional maturing older Joe has taken decades on. As in The Adjustment Bureau, a couple of moments in the company of Emily Blunt proves the tonic — like Rachel Weisz in The Brothers Bloom, she gets to do a great deal more than be someone for the heroes to fight over, and her character nurtures secrets that liven up the third act no end.

There are, of course, references to The Terminator (Garret Dillahunt, from the Sarah Connor Chronicles TV series, shows up in a good cameo as a different type of gat-wielding killing machine) and 12 Monkeys (another of Bruce Willis’ surprisingly frequent ventures into the fourth dimension), when older Joe decides he can solve his problems by murdering the crime boss of the future who is currently a schoolkid, but Johnson takes an unexpected approach to the would-you-kill-Hitler? quandary. There’s one surprise everyone will see coming, but before the film gets there, it does several things — notably, an unforgiveable act any less-independent-minded auteur would probably let himself be talked out of — that come completely out of left field.