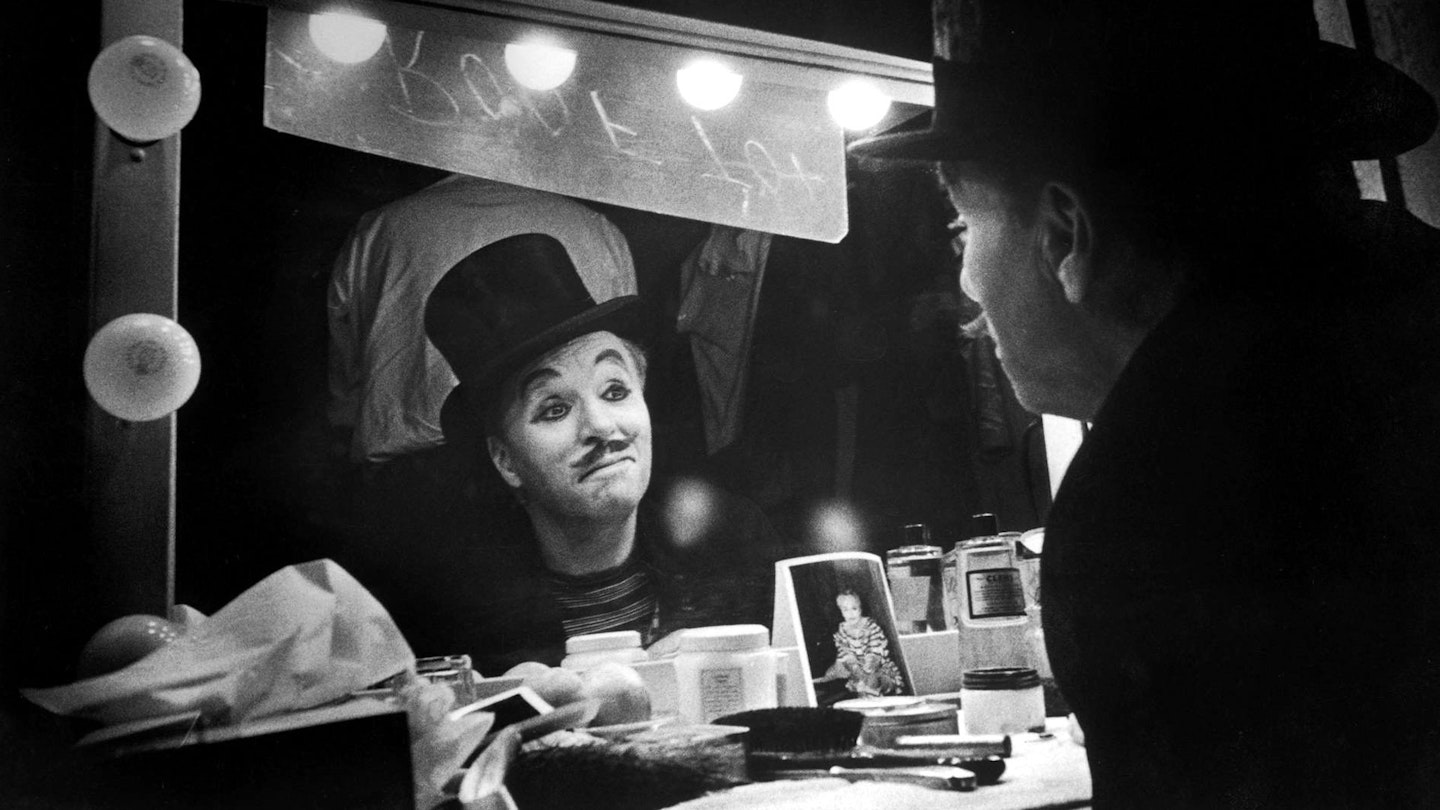

Based on his unpublished novel, Footlights, this was Charles Chaplin's last great film. It may be melodramatic in places and Calvero's philosophising may often be more platitudinous than profound. But Chaplin's work had always combined slapstick and sentiment and he wisely resisted changing a winning formula.

Moreover, it saw him paired for the only time with his lone serious rival as a silent clown, Buster Keaton. However, he spent much of the running time playing opposite Claire Bloom, who was discovered at the end of an extensive search for a new star that included, among others, Anne Bancroft.

Many have seen Terry as the personification of Oona O'Neill, the 18 year-old daughter of playwright Eugene O'Neill, whose steadying marriage to the 54 year-old star in 1943 was the latest in a line of sexual and political scandals that convinced the FBI that Chaplin was an undesirable alien. However, the action abounds with similarly autobiographical references.

Named perhaps with his French nickname, Charlot, in mind, Calvero is an amalgam of Chaplin's own father and vaudevillians Frank Tunney and Leo Dryden, while the scenario is set in London in 1914, the year in which Chaplin first embarked for America. Moreover, his son, Sydney, plays his romantic rival and several other family members take cameos.

But, primarily, this was a valedictory summation of his own career, in what Chaplin was convinced would be his farewell feature. Calvero's passing out of vogue echoes Chaplin's own struggle to please critics and fans alike during the 1940s. But there's nothing defensive or self-pitying about his recollections of past glories. Indeed, this was a proud affirmation of his achievement and a confident avowal that pantomime would survive in other artforms, even if it was no longer considered cutting-edge comedy.

Having decided to premiere the picture back in Britain, Chaplin was denied re-entry to the States and the American Legion ensured that the film had only a limited US release. However, Chaplin won the Oscar for Best Score when Limelight finally opened in Los Angeles in 1972 and he returned to a hero's reception to collect his award.