In Catholic theology, limbo is a nothing place, a joyless chasm between worlds where all hope is gone. That’s not quite the situation here, but it might as well be. Taking his cue from reality — some European countries really do send asylum seekers to remote communities while they wait months, or even years, to hear about their fate — Scottish writer-director Ben Sharrock focuses on four young men subject to unprecedented boredom. There are certainly politics at play here, but also poetry: it’s a very wry, very eccentric story about physical and spiritual displacement.

Set on an unnamed slab of earth in the Outer Hebrides (in fact shot on the Uist islands), this is a town — if you can even call it that — of miserable architecture, brown and beige buildings, degraded radiators and rotting wallpaper. Sad corridors and unloved kitchens. And the world’s drabbest food store. “Please refrain from urinating in the freezer aisle,” reads a note on the wall. And that’s as exciting as it gets. These poor souls have been posted to the planet’s most alienating place, left to, well, exist, or just about. “You know why they put us out here in the middle of nowhere — to try and break us,” says one. It’s an unempathetic rock.

Sharrock doubles down on this muted environment, making art of mundanity, filling it with blank stares as the asylum seekers wait, and wait, and wait. They sit numbly at the absurd cultural classes they must attend, which are run by a bizarre pair of unwittingly offensive instructors (played by Kenneth Collard and Borgen’s Sidse Babett Knudsen), in sequences that seem like they’re from a lost, very dry, very awkward British sitcom. These colliding tones are Limbo’s bread and butter: here, naturalism and broad comedy go hand in hand, in a film simultaneously sad and funny.

Sharrock goes beyond the headlines that reduce refugees to statistics.

Sharrock knows his material — he studied Arabic and Politics for his undergraduate degree, living in Damascus for his third year, just before civil war broke out in Syria in 2011, and he worked in refugee camps in southern Algeria. His familiarity with his subject — and his compassion for those he met and befriended — are both very much evident in Limbo. He goes beyond the headlines that reduce refugees to statistics, swerving the news images of them on boats, zeroing in on individual stories, fractured character studies that nevertheless speak to the situation at large.

The action — or inaction, at least — hovers around Omar (Amir El-Masry), the young musician whose parents, having fled Syria with him, are now having a hard time in Turkey, while his brother is back home fighting. He is forever carrying around an oud (a Middle-Eastern lute-like instrument) that he can’t bring himself to play. It’s a burden. “You walk around like that case is a coffin for your soul,” someone says to him. During phone calls with his parents in the island’s sole phone box — there’s no signal in this Scottish purgatory — he is made to feel guilty for having abandoned them and lazy for having abandoned his music. He’s stuck in all senses of the word, creatively crippled, spiritually struggling, a shell of a man, near breaking point but holding on, and played with emotional precision by El-Masry, who speaks volumes while staring into space.

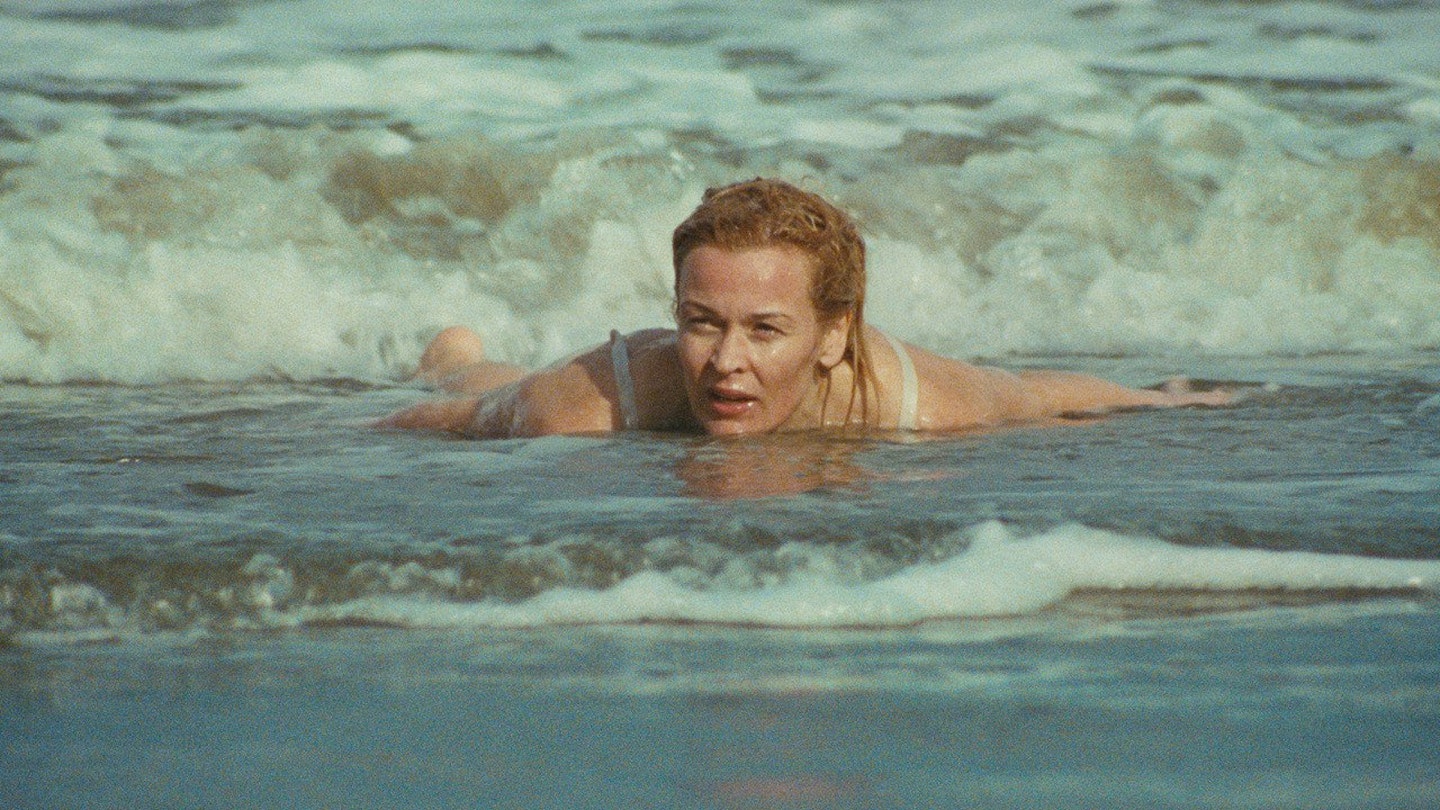

Much of the film is shot, by cinematographer Nick Cooke (who seems to channel Wes Anderson via Martin Parr), in the 1.37:1 Academy aspect ratio, which makes everything feel even more restricted, sometimes for dry, comic effect, sometimes to accentuate this deadening situation, Hutch Demouilpied’s mournful score underlining the sheer state of it all. The film is laced with deadpan absurdism, with a touch of Yorgos Lanthimos, but more surreal: there are racist wheel-spinners, a woman with a dolphin’s head, and a stolen chicken named Freddie Mercury.

Around halfway through, reality gets the edge over the comedy, as it dawns on these young men that their new life in Britain may offer limited options. Even then the tone keeps shifting, and not always harmoniously, the straighter scenes, the earnest ones and the sillier ones not always clicking together. But those lighter touches do elevate it from the bleakness the situation dictates. For good reason, there is a hopelessness to it all. It’s a film that questions what we are without supporting structures. About humanity trying to fight through, humans sticking it out, against the odds. Where any glimmers of goodness seem monumental.