As some poet once put it, "Let's talk about sex, baby". Or rather, if it's any time before the publication of Alfred Kinsey's Sexual Behaviour In The Human Male in 1948, "Let's absolutely not do that. Ever."

These days, it's difficult to imagine the kind of impact that the good doctor's 804-page slab of meticulously compiled rudie-data had on swathes of Americans, who were under the impression that either they were the only person who did the things they did, or that doing the things that they wanted to do would send them straight to hospital, prison and Hell. In that order.

A biologist by profession, Kinsey attempted to investigate humanity's sexual behaviour in exactly the same dispassionate way he had examined gall wasps. He'd collected a million of those, so for his report he interviewed thousands of Americans about their sex histories, asking them the kinds of questions that would normally get you a smack in the mush. The result was a book that both titillated and shocked, but that blew open the debate on what America was getting up to in the sack. But the man at the centre of the brouhaha remained something of an enigma. What were his motives? Was he an impassive scientist or a proselytiser for an early version of free love? Or was he only justifying his own unorthodox sexual identity?

With Gods And Monsters, director Bill Cordon demonstrated he was adept at delicately teasing out the contradictions of complex characters - in that case Frankenstein director James Whale - while leaving just enough unexplained. He pulls off the same feat with the same gentle dexterity here.

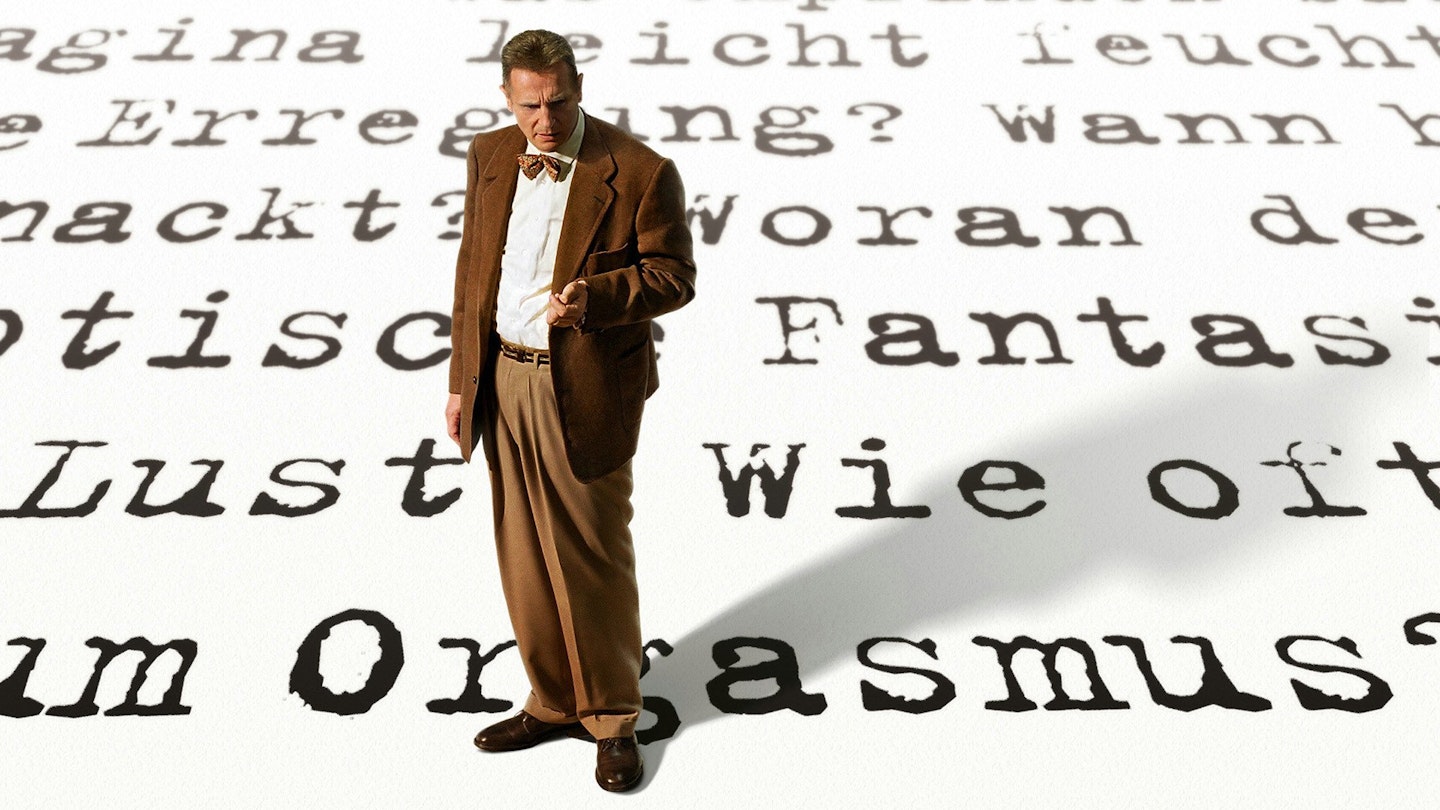

Liam Neeson, as good as he has ever been, delivers a picture of an obsessional scientist who, while certainly dedicated to truth, could also be interpreted as using his research both to work out his own sexual nature (he finally placed himself as a three on his infamous straight/gay table, where one is the straightest and six the gayest) as well as to fashion a hammer out of his reams of stats with which to smash the repressive society represented by his bigoted, priggish father (John Lithgow).

The supporting cast is universally impressive: there's something deliciously savoury about casting Frank-N-Furter himself (Curry) as a prudish 'hygiene' lecturer; Laura Linney is convincing as the kind of unconventional wife who could put up with her husband's obsession while Lithgow, as Alfred's father, at first appears to be essaying a slightly less nuanced version of the sexually repressed killjoy preacher he played in Footloose (here is a man who believes that the world went to Hell in a haycart with the invention of the zip-fastener) before transforming his character into something much more moving. But it's Peter Sarsgaard, easily the most promising discovery of the decade so far, who really shines as assistant researcher and sexual adventurist Clyde Martin, a man who manages to seduce both Kinsey and his wife and who indicates that, desirable or not, a genie has definitely been let out of the bottle.

Critics will say that Condon is unduly lenient on Kinsey. His alleged scientific failings are all but glossed over, there's the odd minor stylistic misstep - Kinsey's marriage lectures are uncomfortably reminiscent of the sex education sketch in Monty Python's Meaning Of Life, and there's one too many cheap sniggers at the cutesy sexual ignorance of rural rubes. But, in a year when biopics have been criticised for either being constipated with detail (Alexander) or frustratingly inconclusive (The Aviator), this is almost as good as the genre gets.