Claude Berri spent six years trying to acquire the rights to Marcel Pagnol's 1962 Water in the Hills dualogy. Inspired by Pagnol's own 1952 feature, Manon Des Sources, the story chronicled the destruction of an educated outsider by avaricious provincials, who meet their match in his free-spirited daughter. Berri raised much of the $18 million budget required for Jean de Florette and Manon des Sources himself and reaped a handsome profit when the films became box-office smashes around the world.

There were many French critics, however, who denounced his heritage approach and accused Berri of returning to the literate style of film-making that had been branded `cinéma du papa' by François Truffaut and the young guns of the influential journal, Cahiers du Cinéma.

There's no question that Bruno Nuytten's Provençal landscapes tend towards the pictorialist. But Berri was always careful to integrate the characters within their environment, to emphasise both Jean's isolation outside the private paradise that eventually betrays him and César and Ugolin's grimy identification with the soil they're prepared to lose their souls to obtain.

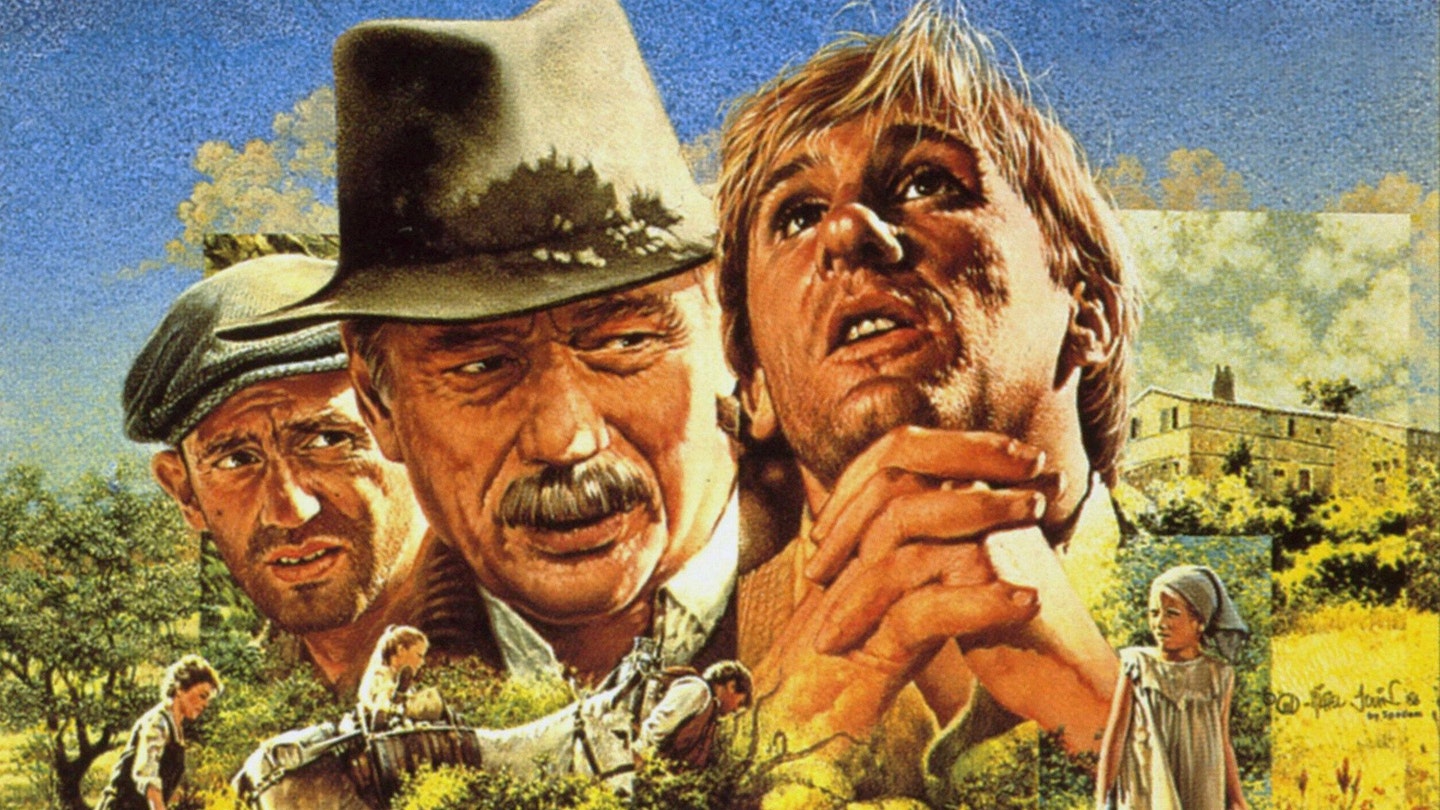

Berri and Gérard Brach prided themselves on the fidelity of their adaptation. However, there's little of the realism that Alexander Korda, Marc Allégret and Pagnol himself invested in his magisterial Marseilles trilogy (Marius, 1931; Fanny, 1932; César, 1936). Yet, the cast manage to rise above the rustic chic of Bernard Vazet and Marcel Laude's designs and the emotive cues of Jean-Claude Petit's score, with Gérard Depardieu literally throwing himself into the role of the hunchback reduced to becoming a beast of burden to carry the water on which his idyll depends. But his flamboyant turn gains additional power from the response of his neighbours in Les Bastides Blanches, as Yves Montand and Daniel Auteuil expertly alternate between faux concern and calculated cruelty with a conviction that casts a chill over the sun-parched vistas.