Warning: this review contains mild spoilers

Christopher Nolan is a director whose name has, quite literally, become synonymous with realism. The Nolanisation of cinema, which made the gloomy streets of Gotham a bridge between the fantastical and the commonplace, now grounds countless fancies within the mud of our reality. With Interstellar, arguably his first ‘true’ science-fiction project, Nolan inverts expectation once again, with a film rooted in the mundanity of maths homework but spliced with the fantastic.

Born a year after the Apollo landing, Nolan grew up in the aftermath of the space race, when young eyes still turned upwards in wonder. Decades later, with the Space Shuttle decommissioned and children staring blearily down at the glow of their smartphones, it’s his disappointment at NASA’s broken promise that forms the driving force behind Interstellar.

Opening, tellingly, on a dusty model of the shuttle Atlantis, the film’s near-future setting sees humanity starving, squalid and devoid of hope. Eking out an existence in a post-millennial Dust Bowl, Matthew McConaughey’s Cooper and his two children — ten year-old daughter Murph (Mackenzie Foy) and her older brother Tom (Timothée Chalamet) — lead a life of agrarian survivalism (while, hearteningly, still reading a great many books). But in Cooper we find a new man cut from old cloth: an all-American hero pulled straight from Philip Kaufman’s The Right Stuff. Played with a drawling, Texan swagger underpinned by startling emotional depth, he is Nolan’s most traditional lead to date, embodying the wide-eyed wonder of the director’s youth; a man for whom we are “explorers and pioneers, not caretakers”, who casts his lot among the stars as the human race’s last, best hope.

With the ailing Blue Planet left behind, Interstellar shifts smoothly into second gear. The black abyss rolls out like Magellan’s Pacific; an unknowable frontier, final in a way that Roddenberry’s never was. According to über-boffin co-producer Kip Thorne, the spherical wormhole (it’s three-dimensional, obviously) and the spinning event horizon of the film’s black hole (named Gargantua) are mathematically modelled and true to life. Sitting before a 100-foot screen, though, you won’t give a toss about equations because Nolan’s starscape is the most mesmerising visual of the year. Gargantua is as captivating as it is terrible: an undulating maelstrom of darkness and light. Like the Hubble telescope on an all-night bender, this is space imagined with a dizzying immensity that would make Georges Méliès lose his shit.

The planets themselves are no less spectacular. Let The Right One In cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema (replacing Nolan regular Wally Pfister) captures the bleak expanse of southern Iceland as both a watery hell with thousand-foot waves and an icy expanse where even the clouds freeze solid. With more than an hour of footage shot in 70mm IMAX, you’ll want to park your arse in front of the biggest screen available to fully appreciate the spectacle.

In contrast to the grandeur of space, the ship itself is a scrapyard mutt. Modular and boxy, the Endurance looks like an A-Level CDT workshop, with no hint of aesthetic flourish or extraneous design. Ever the practical filmmaker, Nolan has constructed a functional, utilitarian vessel. Its robotic crew-members, TARS and CASE, are ’60s-inspired slabs of chrome; AI encased in LEGO bricks that twist and rearrange (manually operated by Bill Irwin — there’s no CG trickery here) to perform complex tasks with minimalist efficiency.

Beneath Interstellar’s flawless skin, the meat is bloodier and harder to chew. The science comes hard and fast, though Nolans Christopher and Jonah shore up the quantum mechanics with generous expository hand-holding. Astrophysics is the vehicle not the destination, however, and Interstellar’s gravitational centre is far more down to Earth. Embodied by Dylan Thomas’ Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night (quoted in the film at several points), this is a defiant paean to the human spirit that first took man to the stars. But far more than Thomas’ villanelle, Interstellar scales the heights and plumbs the depths of humanity, pitting the selfish against the selfless, higher morality against survival instinct. As Cooper, scientist Brand (Anne Hathaway) and crew draw closer to their destination, complications require tough decisions; the sanctity of the mission wars with the hope of a return trip. That the undertaking isn’t quite as advertised doesn’t come as a shock, but the cruelty of the deception lands like a body blow. Nature isn’t evil, muses Brand (played with soulful nuance by Hathaway). The only evil in space is what we bring with us.

When Interstellar began life back in 2006, Steven Spielberg, not Nolan, was the man in the cockpit; a presence still felt in the relationship between Cooper and Murph. The betrayal of a child abandoned is potent from the outset but the guilt is magnified tenfold when the Endurance’s first stop, within the influence of the black hole, means that a few hours stranded planet-side result in two decades passing back on Earth. Cooper’s tortured face as he watches his family unspool through 20 years of unanswered video missives is agony, raw and unadorned. Beneath everything else, this is a story about a father and his daughter, the ten-year-old giving way to Jessica Chastain’s adult in the blink of a tear-filled eye.

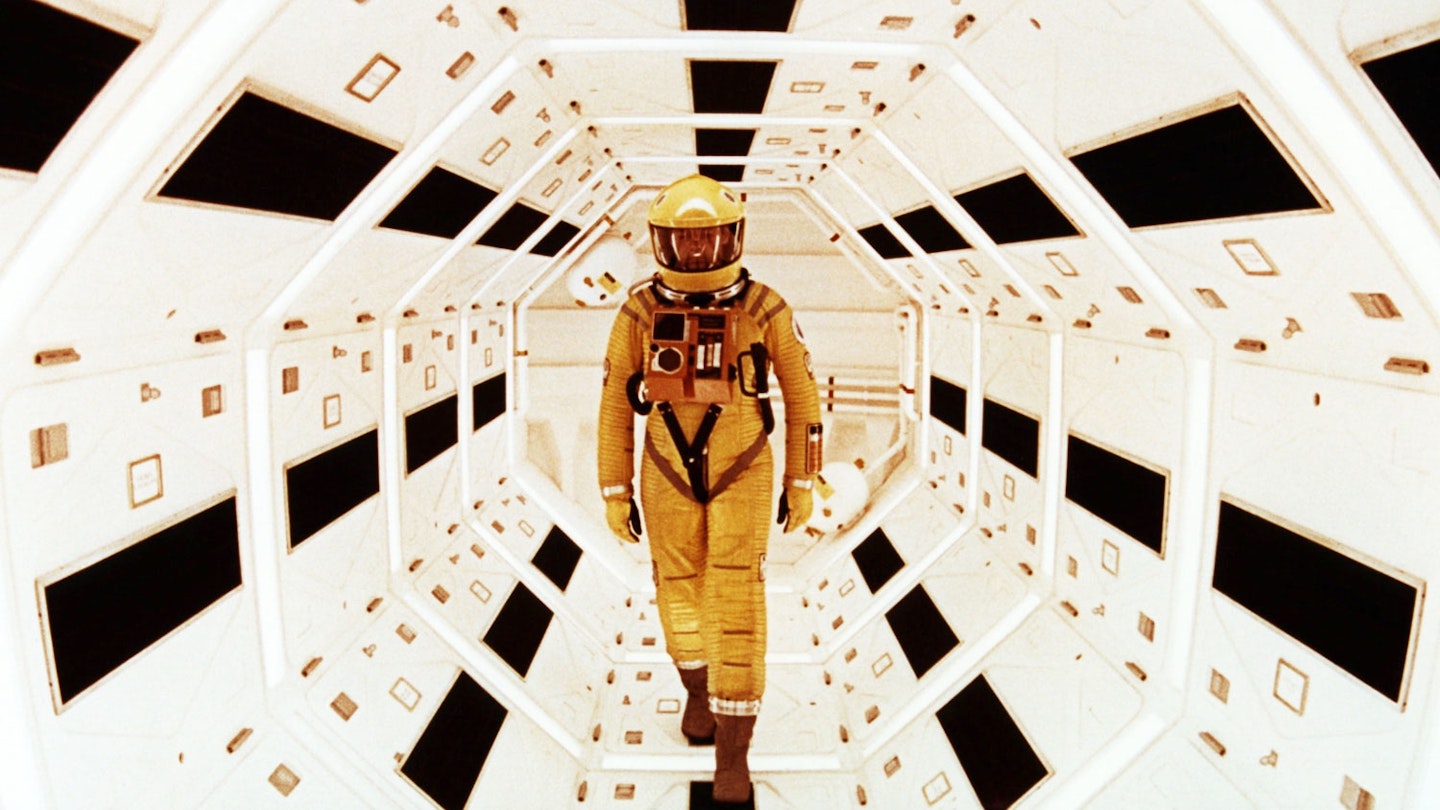

With the endless pints of physics chased by shots of moral philosophy, Interstellar can at times feel like a three-year undergraduate course crammed into a three-hour movie. Or, to put it another way, what dinner and a movie with Professor Brian Cox might feel like. The final act compounds the issue, descending into a morass of tesseracts, five-dimensional space and gravitational telephony. It’s a dizzying leap from the grounded to the brain-bending that will baffle as many viewers as it inspires. More than the monolithic robot and his sarcastic, HAL-nodding asides (“I’ll blow you out of the airlock!”), it’s the psychedelic, transcendental climax that feels most indebted to Kubrick’s 2001; something that will undoubtedly prompt some to accuse Nolan of disappearing up his own black hole.

Inception posed questions without clear answers. Interstellar provides all the answers — you just might not understand the question. This is Nolan at his highest-functioning but also his least accessible; a film that eschews conflict for exploration, action for meditation and reflection. This isn’t the outer to Inception’s inner space (his dreams-within-dreams are airy popcorn-fodder by comparison), but it does wear its smarts just as proudly. Yet for the first time, here Nolan opens his heart as well as his mind. Never a comfortably emotional filmmaker, here he demonstrates a depth of feeling not present in his earlier work. It’s no coincidence that the film’s shooting pseudonym was Flora’s Letter, after Nolan’s own daughter. Interstellar is a missive from father to child; a wish to re-instil the wonder of the heavens in a generation for whom the only space is cyber. Anchored in the bottomless depths of paternal love, it’s a story about feeling as much as thinking. And if the emotional core is clumsily articulated at times (Brand’s “love transcends space and time” monologue being the worst offender), it’s no less powerful for it.

As a light-year-spanning quest to save the human race, this is the director’s broadest canvas by far, but also his most intimate. And against the alien backdrop of black holes, wormholes and strange new worlds, Interstellar stands as Nolan’s most human film to date.