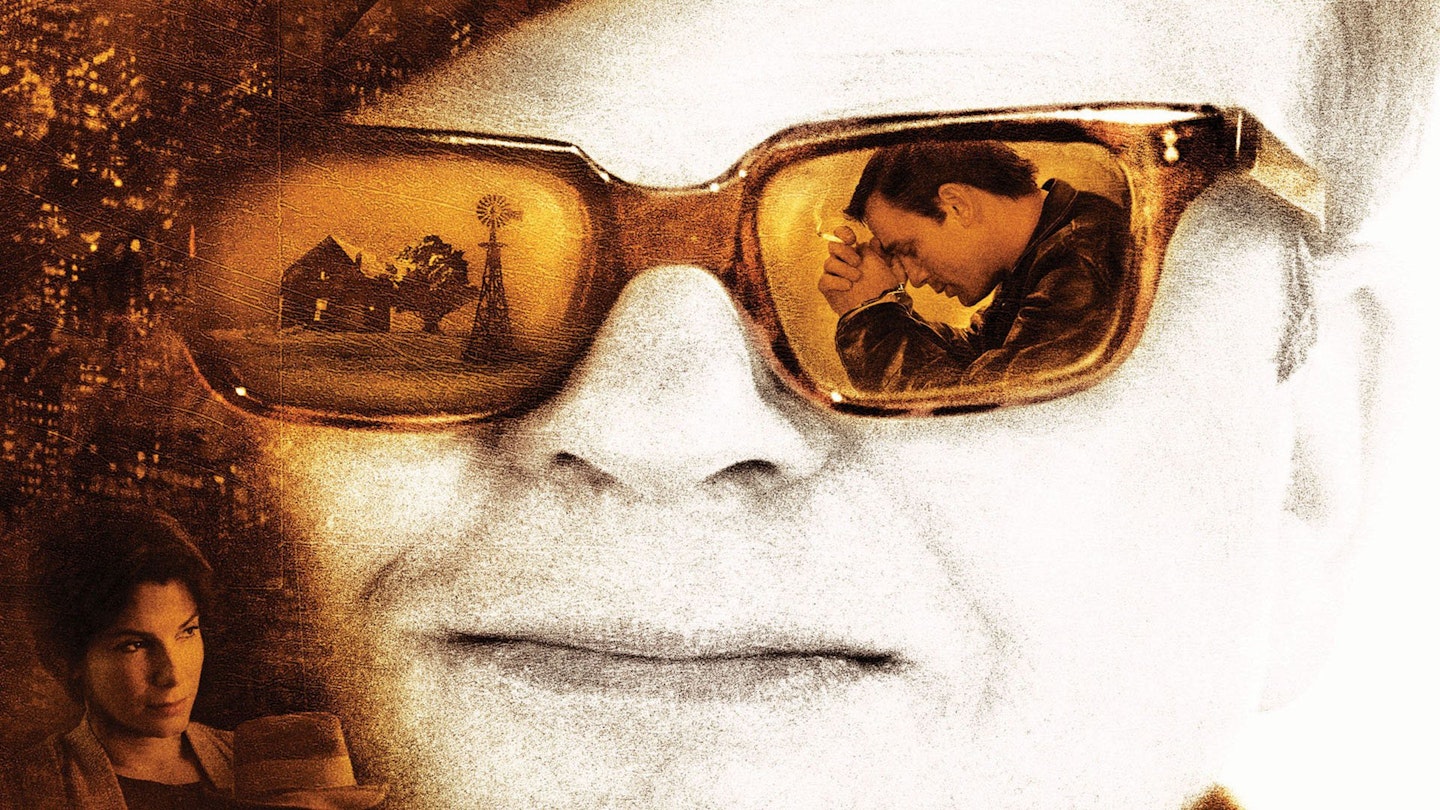

Last year’s Capote, an enigmatic account of Truman Capote’s bid to re-invent narrative journalism, suggested that a dark heart lies at the centre of even the brightest flame. This year’s less mysterious Infamous spells that out. Both films are drawn from books, this one sifting through George Plimpton’s portrait, a collection of interviews with socialite insiders delivered with a hefty side-order of tittle-tattle that would have delighted the fey literary elf himself. Like Capote’s In Cold Blood, however, Doug McGrath’s film delves beyond the reported accounts to eke out the humanity of its primary protagonist, and while Infamous may lack the subtlety of its predecessor, it is, arguably, much more fun.

Much of that merriment is served up in the first act, as McGrath whisks the audience through the vapid New Yorker social scene, peppered with illustrious names (both the real characters and the stellar cast). In the very first scene, Gwyneth Paltrow’s Kitty Dean croons What Is This Thing Called Love?, Cole Porter’s rueful lyrics hinting at the movie’s final destination — for while 2005’s Capote covered ambition and guilt, Infamous is a parable of love.

The bond between the effeminate writer and the youngest killer, Perry Smith, was only hinted at in last year’s movie. Here it is bellowed from the prison rooftop, as the troubled souls discover a shared past and a caring present, all the more poignant for the lack of a conceivable future.

Toby Jones’ portrayal of Capote is every bit the equal of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s; both Sandra Bullock’s Harper Lee and Jeff Daniels’ Alvin Dewey, meanwhile, eclipse their predecessors, but the film is somewhat undone by Daniel Craig’s Perry. The casting is unusual, as in reality both Capote and Smith suffered from ‘little man’ syndrome. Even if the audience is willing to forgive this inconsistency, Jones and Craig’s relationship fails to spark — at times, it seems as flat as the Kansas landscape, rendered so hauntingly by the voluptuous cinematography.

Both Capote and Smith yearned to create a masterpiece, and together they achieved that goal, even if both men lost their life, Smith literally, and Capote metaphorically, his creative fire doused by the watershed of his affection.