If you know nothing else about Inception, at least know this: it is not a trick. It is ingenious but not crafty, knotty but not duplicitous. It has neither Memento’s method conceit nor the smoke and mirrors of The Prestige. To contrast it with the latter, in particular (fine film though that is), is to appreciate the difference between stage-magic and a real miracle.

The director-as-magician analogy feels least tired when applied to Christopher Nolan, given his body of work, its formal and mental layers and precisely engineered reveals. At best, this approach can be exhilarating. At worst — as with the narrative drip-feed of Insomnia, his weakest picture — it is obfuscation masquerading as artistry, aka not half as bloody clever as it thinks it is. Given its setting is largely the subconscious, though, Inception can’t work with a rug-pull denouement. Every scene — let alone the movie — could be punctured with that postscript beloved of primary school story scribblers: “And I woke up and it was only a dream...” So, don’t brace for a “ta-dah!” moment — it will impede your enjoyment and waste your time. Instead, marvel at the effrontery of a filmmaker who asks you to emotionally invest in avowed mental constructs — and succeeds. In one sense, admittedly, this is what every filmmaker asks us to do: engross ourselves in their imagination. The movie, then, could be interpreted as being about craft and inspiration — one character even says, of constructing the architecture of dreams, “It’s just... pure creation.”

But there are bigger things in play here than simply Art, and Nolan isn’t given to self-referential indulgence. This is about life and death and what might be beyond and between. It is also about blazing gun battles, zero-gravity fist fights and stars you’d like to sleep with. Fret not, Batfans — Nolan hasn’t turned into Andrei Tarkovsky. The muscular action that distinguished his Bruce Wayne pictures is again in evidence, but whereas Gotham in the Nolanverse is bound by at least some constraints — you know, little things like physics — here all bets are off. It’s not that Inception doesn’t have rules: like any convincing science-fiction, it has rules and boundaries it will not break. But those boundaries are pretty broad — they are the limits of each character’s imagination. The images deserve to be untarnished by much explanation — you should see them for yourself and on the biggest screen you can (it’s coming to IMAX — book now) to best appreciate Wally Pfister’s excellent, expansive photography. Funny, though, how moments that make the memory boggle when you recall them pass naturally in the moment because you are rooted in the world Nolan has created, in the reality(s) of the characters. This is testament to the physical prowess of the production and thorough thought that’s created this world, but also to the actors.

Some rise to particularly fascinating challenges (hello, Tom Berenger) and some surprise — principally Cillian Murphy, who can do danger and insolence in his sleep, but here shows a tenderness and vulnerability crucial to the story. Others exert a personality and appeal on parts that on the page would have played very close to ‘types’ — particularly Ellen Page, exuding a prim sexiness as, really, Basil Exposition, and Joseph Gordon-Levitt, who somehow manages to appear both ambiguous and dependable as essentially a sidekick. The pair share one of the movie’s best comic beats, too, though most of the sly laughs come from Tom Hardy’s roguish Eames.

It will be fascinating to read the hypotheses that percolate about Inception after release and no doubt what characters are called will be explored. That Page is Ariadne — the name of a figure in Greek myth who guides a hero from a maze — has already been noted. Eames shares his name with seminal designers/architects Charles and Ray, who made a celebrated short film, Powers Of 10, about the magnitude of the universe. Marion Cotillard is Cobb’s wife, Mal — which means “bad”, but can also derive from the Hebrew for messenger or angel. Cobb itself comes from Jacob, who, when fleeing from his murderous brother in the biblical book Genesis, dreamt of a ladder to heaven...

Based on his previous behaviour, Nolan isn’t likely to explain what he thinks Inception is actually about, but it’s certainly possible to see it as a blockbuster allegory about grief, faith and the desire for an afterlife — to be reunited with those we love and have lost (those with even a passing knowledge of Catholicism may note an interesting use of the word ‘limbo’). You could argue it’s about suicide and the fears and hopes that can both power and prevent it (for in that sleep of death, what dreams may come?), just as was Soderbergh’s Solaris. Nolan, though, doesn’t muse; he motors. This is no sombre meditation. The themes are there to be explored (there will be more theories about this movie than about the killing of JFK), but you can just as well sit back and enjoy the spectacle.

And what a spectacle.

In terms of scale and style it is, as Nolan intended, comparable to Bond’s best excursions — yet filtered through a brain-frying, subconscious-spelunking, time-dilating structure that boldly frames action sequences around each other. So we get an explosive Arctic mountain vault-storming within a zero-gravity scramble within a vehicle-crunching chase. In effect, the set-pieces are simultaneous. Which is insane, but brilliant as, while he at times boggles through the necessarily complex editing, Nolan never corrupts his multiverse’s internal logic.

When you’re not basking in the visuals, you can always lean into DiCaprio and appreciate the emotion. He anchors everything. An actor who has long borne the blessing and the burden of being hailed a genius before he was even a man, he has never been less than good, but can appear either callow or try-hard, like a child dressing in daddy’s suit. Not here. He shows a depth of feeling rivalled only by his work in Shutter Island. To deliver two such turns in a career would be impressive. In a year, it’s just showing off. What makes it work, really, though, is how unfussy he is, how unselfish — there’s no showboating. Good as he is in The Departed or Gangs Of New York, you could sometimes feel the Weight of his Acting. Here, paradoxically, he appears effortless, even though he’s the beam on which the whole mighty edifice rests. It’s because you believe his journey, his heart, that you buy into Inception. If he failed, so would the movie. This isn’t the sort of performance that usually wins Oscars — it’s not ostentatious or superficially transformative, but by God it is brilliant. The strength of it is that you remain emotionally engaged, even if you’re not entirely sure what’s going on. The third act makes Memento seem about as complex as Bear In The Big Blue House. And while there is remarkable clarity given the complexity, you are pummelled with information and have to keep up — pay attention, figure it out.

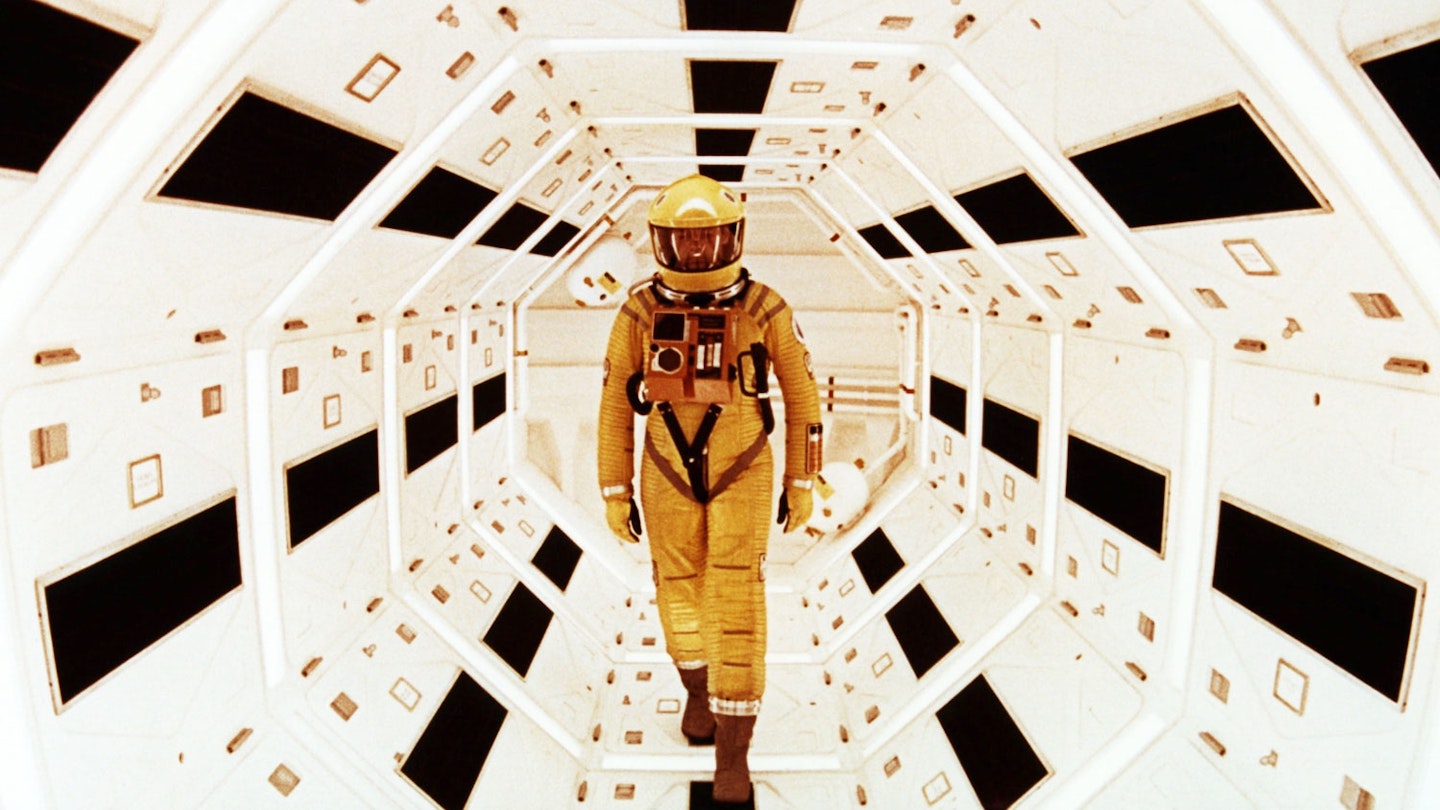

Only repeat viewing will reveal if this comparison is truly justified, but it feels like Stanley Kubrick adapting the work of the great sci-fi author William Gibson (Neuromancer) — except Nolan appears to like people more than the 2001 auteur. So, you have a film that embraces intellect and emotion but also sheer entertainment — that can include a character staring at what looks like one of Francis Bacon’s tortured self-portraits, but also has the best EXPLODEY BUILDING sequence since Zabriskie Point. That film was a notorious bomb, ignored by audiences and pilloried by critics. And some, who may find Inception exposition-heavy and bewildering, will no doubt argue that, drunk on the freedom of The Dark Knight, Nolan has spent $170 million disappearing up his own arse. He hasn’t. On this form, wherever he goes next, be it Batman 3 or something else, we’ll be the first in line to follow.