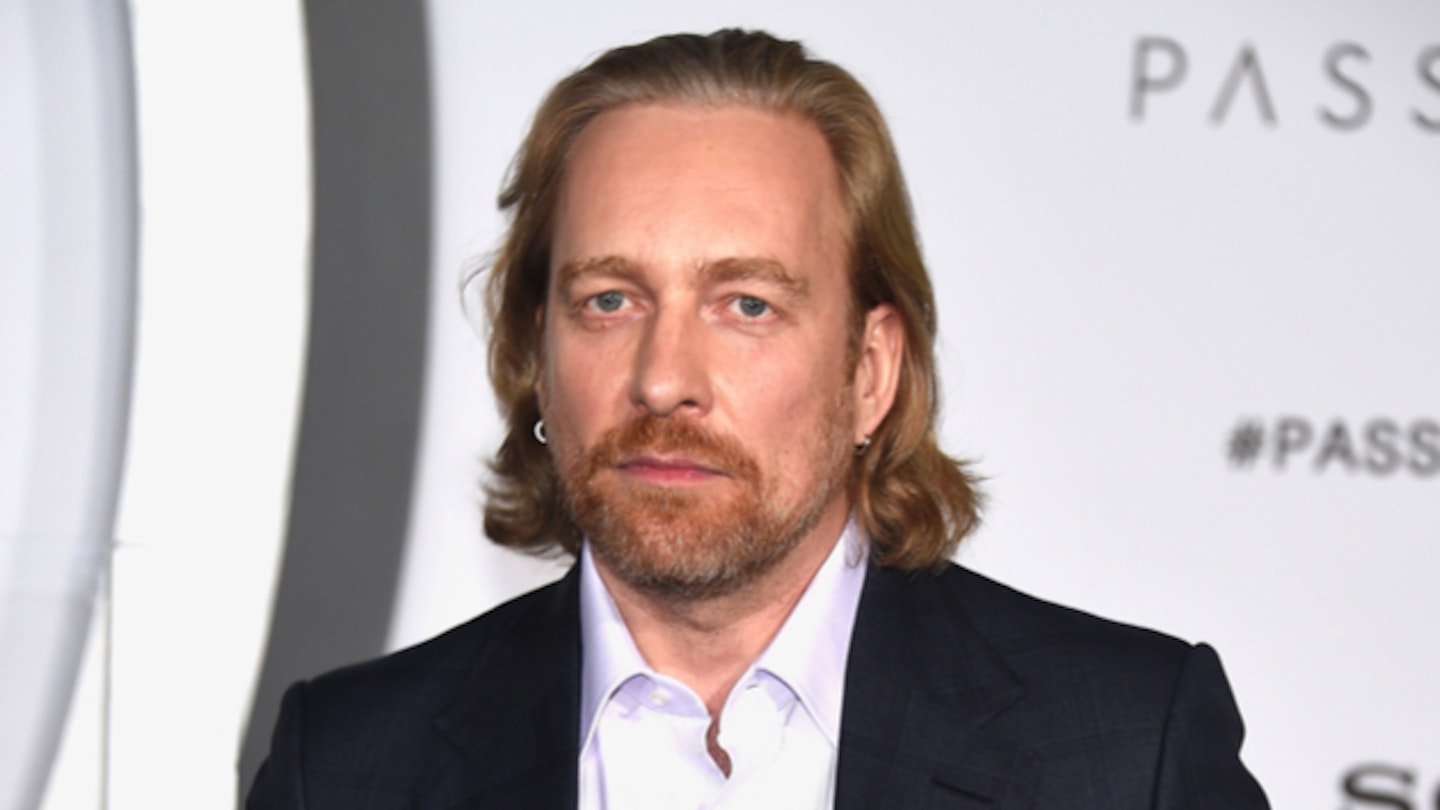

Morten Tyldum's last movie was Headhunters, a slick, sick and witty thriller that suggested a solid future in Hollywood despatching the likes of Mark Wahlberg and Liam Neeson down dark American alleyways in pursuit of smirking Eurovillains. And yet here we find the Norwegian director only a little further west, dealing with cut-glass Queen’s English accents, cucumber-sandwich picnics on immaculate lawns, and a very Union-Jack-bunting story of polite wartime triumph.

On the surface, The Imitation Game is the kind of crisp, British prestige piece you could suspect of cashing in on Downton fever (one character is played by Allan Leech, aka Tom Branson), while passing off TV’s Sherlock (Benedict Cumberbatch) in the guise of another stand-offish, mystery-solving genius. But if you know even a little about Alan Turing, you’ll know not to trust such a smooth surface. You’ll also understand that Tyldum’s latest film — from a script on the 2011 Black List — isn’t such a crazily far cry from the murky, pacy Headhunters.

Tyro screenwriter Graham Moore couldn’t have made a more impressive debut. It’s a tight and wiry plot with barely an ounce of fat on its bones. There is a gripping rhythm to it, each scene a loud finger-snap which draws you back and forth between a trio of elegantly entwined narrative strands: 1) Turing’s arrival at Hut 8 in Bletchley Park and his cerebrally Herculean efforts to crack the ever-mutating Enigma code, by which German U-boats communicated; 2) the 1951 police investigation into the professor for his homosexuality, which was then still criminal in the UK; 3) Turing’s schoolboy years in the late ’20s, where he had to contend with both vicious bullying and forbidden love.

At times there are concessions to convention, on-the-nose scenes which feel like they’re pushing a neat point rather than relaying reality (putting a Bletchley codebreaker’s sibling on a suddenly doomed battleship, for example), while certain historical facts, such as the Polish influence on the mechanics of British wartime cryptanalysis, are overlooked.

Yet all this is hard to berate. Compare The Imitation Game with 2001’s Enigma, another Bletchley-based thriller (a fictionalisation of the cypher-cracking efforts by Turing’s team), and it’s like racing a thoroughbred against an asthmatic nanny-goat — almost embarrassing how much better this is, despite Enigma’s Michael Apted/Tom Stoppard/Robert Harris pedigree. Moore’s opening line, spoken by Cumberbatch, is, “Are you paying attention?” After a few minutes you’ll realise it’s virtually impossible not to.

The key to The Imitation Game’s success is the way it seamlessly combines its thriller and biopic elements: the story of Turing, it posits, is the story of the Enigma codebreaking. If you leave him out of it you might as well be making U-571. There’s more, too. It’s also, in part, the story of the birth of artificial intelligence (Turing being the bona fide genius whose ‘Turing machine’ pre-empted the computer), and a platonic love story which deals with Turing’s very real relationship with fellow cryptanalyst Joan Clarke (Keira Knightley). Plus, amid all its talk of crosswords and algorithms, there are four puzzles happening at once: 1) the main puzzle of the code, which is energised by the fact that every attempt to crack it before the Nazis change it up is a desperate, matter-of-life-and-death race against the clock; 2) the puzzle of the Soviet spy who may or may not number among Hut 8’s workers; 3) the puzzle of the 1951 reported break-in to the inscrutable professor’s home in Manchester, during which nothing was stolen; 4) the puzzle of Alan himself — who is this “odd duck”? What makes him tick? Why is he so rude? “The problem,” he narrates of his childhood, “began with the carrots...”

... And ends, in 1954, with a cyanide-laced apple. There is tragedy at both ends of the chronology, and connecting them is Benedict Cumberbatch, delivering his finest big-screen performance yet. He seethed as the übermenschy Khan in Star Trek Into Darkness, he roared as the vainglorious Smaug in the last Hobbit movie, but here he folds in on himself and buttons that dark-tinged charisma right down. It might not be an entirely accurate portrayal (the real Turing doesn’t appear to have been quite so walled-in), yet Cumberbatch’s almost paradoxical blend of supreme self-confidence and intense shyness rings true, especially in the way the peerless logician’s mind of his Turing can’t always process the confusions of human interaction (“People talking never say what they mean”).

Turing didn’t have the easiest professional relationship with his military superiors and Cumberbatch clearly relishes those moments in the script where Moore milks this for dramatic effect. The first encounter between Turing and Bletchley’s Commander Alastair Denniston (Charles Dance, giving it a bit of Tywin) must rank as one of cinema’s most delicious job interview scenes: “Are you a bloody pacifist?!” Denniston seethes incredulously, after Turing displays his customary lack of tact. In Cumberbatch’s sure hands, Turing is less a force of nature than a passionate force of logic and integrity — a bold and beautiful mind. He displays far more than an Oscar-baiting repertoire of tics and twitches. There is a bright, burning inner life in evidence, too, taking us beyond the flashbacks, flash-forwards and neat dialogue beats. It’s a tough thing to perform, but Cumberbatch aces it.

Is it a complete portrayal? No. The fact that Turing’s close friendship with Joan Clarke is given more prominence than his homosexual relationships has already elicited disapproving tuts. His further, post-War work on computers is skimmed over. But does it need to be complete? Again, we return to the core strength of Tyldum’s film: that it pursues the dramatic twists and turns while exploring the man. It remains a supremely impressive balancing act, and no less a tribute to a truly great Briton for that.

Turing wasn’t granted a pardon for his ‘crime’ until last year. That it’s taken so long for a fitting cinematic testament to his brilliance is very much mitigated by the fact that The Imitation Game is one of the most entertaining and engaging films of the year so far.