The whole history of special-effects cinema forms a closed loop in Martin Scorsese’s adaptation of Brian Selznick’s children’s book, The Invention Of Hugo Cabret, as Georges Méliès’ 1902 masterpiece, A Trip To The Moon, is digitally rejigged as a modern-day 3D spectacle. Though The Aviator was incidentally about a filmmaking visionary and New York New York and The King Of Comedy are showbiz stories, this is surprisingly the first Scorsese built entirely around the dominant passion of his own life — cinema itself.

Like this season’s The Artist, with which it would make an overpoweringly emotional film fan’s double-bill, this is a French-accented Valentine to the wonders of the movies and a concerted attempt to redeem modes of filmmaking — and the great creatives who pioneered them — once cast aside in a rush to embrace the next thing. The Artist goes so far as to be an Academy-ratio, black-and-white silent movie, aping the kinds of films its tragicomic hero makes, but Hugo finds Scorsese — the most heavyweight director to make a 3D movie since Alfred Hitchcock delivered Dial M For Murder — wholly embracing the possibilities of contemporary film technology in the way Méliès did in his day. The movie is assembled with an obsessive delight in a combination of magic and mechanics, which unites his young and old heroes, a stage conjurer-turned-filmmaker and a lad with an inherited knack for fixing clockwork contraptions.

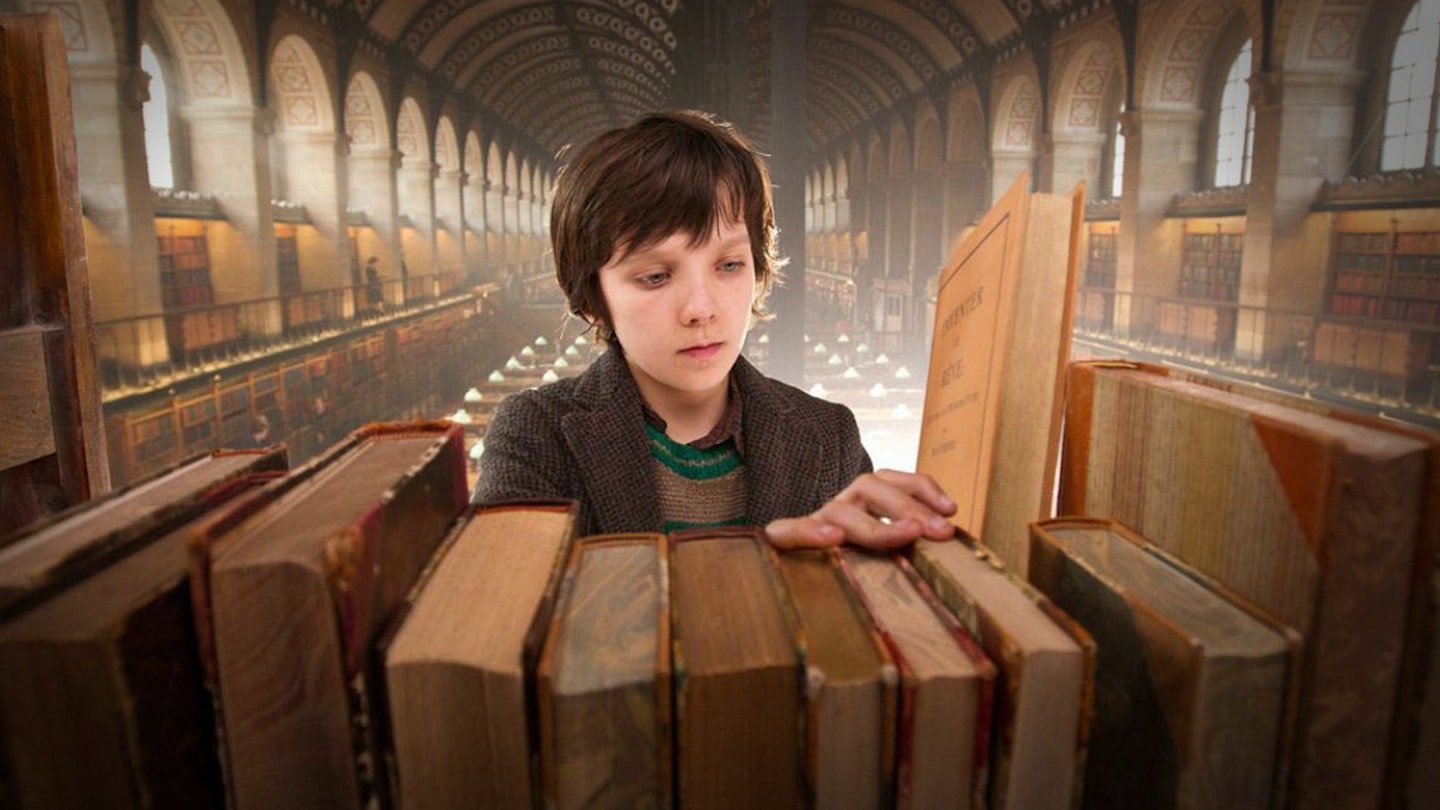

Much of the film is confined to one single, vast location — a richly detailed, realistic-yet-fantastical recreation of a great Parisian railway terminus, which is also a vast clock through which Hugo (the not-too-cute Asa Butterfield) scurries. There’s a touch of Amélie in the array of unfulfilled secondary characters nudged through their own sub-plots, but only because Scorsese looks to the same French films of the 1930s which informed that hit.

Avoiding Clouseauism, these Parisians have English accents: Chloë Grace Moretz seems to channel Jenny Agutter, while Sacha Baron Cohen’s crippled child-catcher is a perfect Peter Cook. In love with the movies, this also embraces all forms of imagination, with Christopher Lee fondly cast as a non-sinister bookseller dispensing Jules Verne and Robin Hood; Isabelle (Moretz) is his disciple as Hugo idolises filmmaking, experimenting with new words and insisting on the adventures to be had in a library.

Hugo’s personal story features serial-like scrapes: an homage to Harold Lloyd’s clock-face dangling which ups the ante in peril, and dream sequences in which the boy becomes a clockwork cyborg or causes a spectacular train crash. It gets round at last to a flashback dramatisation of the pre-War world of silent filmmaking which is also an enduring love story. In sequences guaranteed to make all true cinephiles go misty-eyed, we witness the creation of silent visions in an all-glass studio (to let in the sunlight necessary for filming before the invention of arc lights), a world as full of magic as any modern blockbuster.