Harka is the second film in the last year to grapple with the hangover of Tunisia’s Jasmine Revolution and, as with Youssef Chebbi’s Askhal, it uses the self-immolation of Mohammed Bouzzazi (which sparked the Arab Spring) as a thematic jumping-off point. But where Chebbi focused his lens on agents of the system, here director Lotfy Nathan bleakly confronts the ongoing effect of bureaucratic marginalisation through the struggle of one young man.

In his sporadically thrilling narrative feature debut, the Egyptian-American filmmaker is not subtle about the role fuel and fire plays in this story. Ali (Adam Bessa) is a heavy smoker who trades in contraband gas. Cinematographer Maximilian Pittner trains the camera on his fuel cans, stove burners and smoke dancing around Bessa’s slight frame in some pointed foreshadowing. Ali might feel invisible in society but Pittner’s intimate camerawork makes sure you’re paying him close attention.

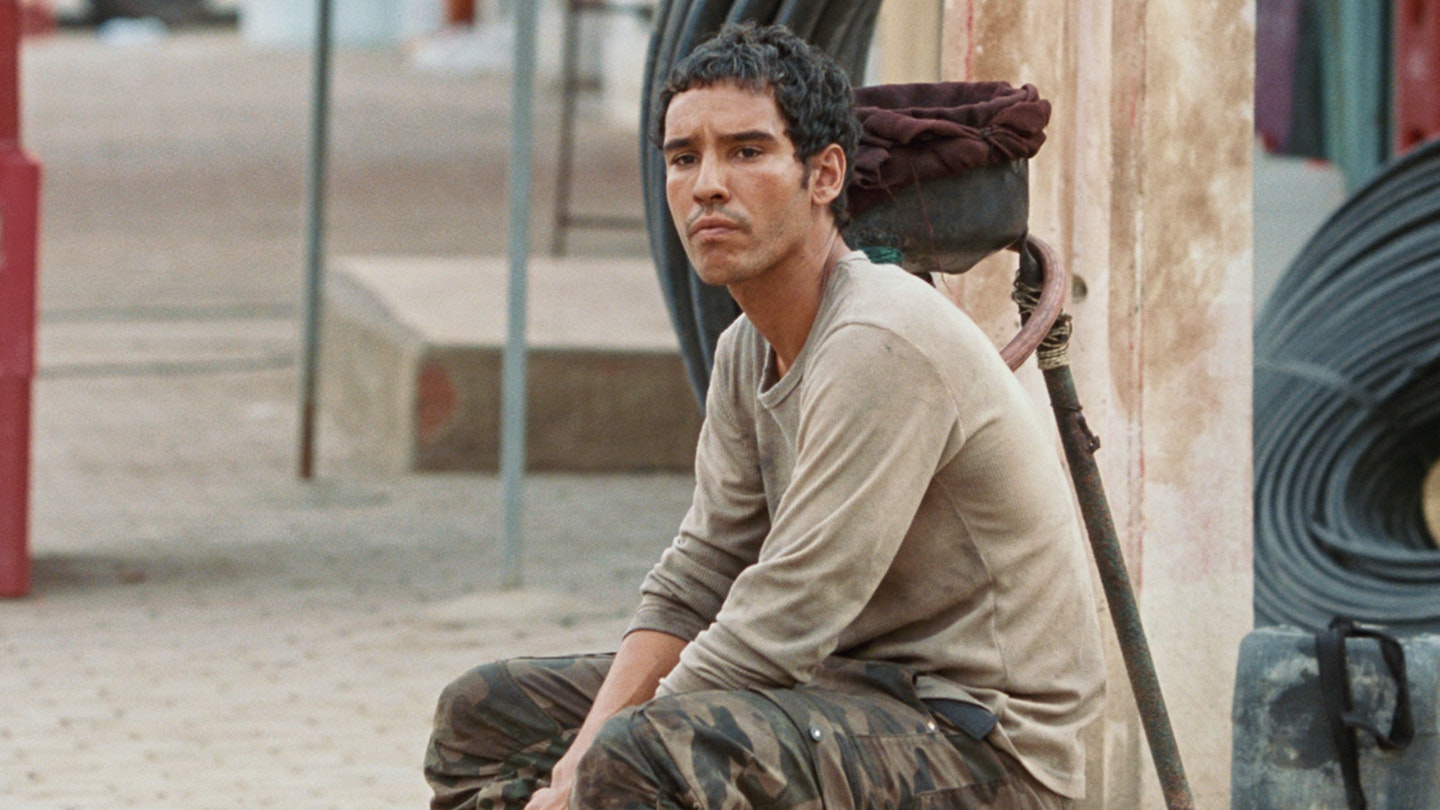

Adam Bessa’s profound performance prevents Ali from simply fitting the angry-young-man trope.

Rage is fueling Ali’s questionable decisions and Eli Kezler’s ominous score tracks his harrowing trajectory. A lighter refrain dedicated to his younger sister Alyssa (Salima Maatoug) tempers the darkness, as does her gentle voiceover that strives to understand her brother’s fracturing psyche. Alyssa’s namesake is Tunisia’s legendary founder and queen of Carthage, Elissa; it connects the broken present with the country’s prosperous past, adding a sense of hope through a charming female character spiritedly rendered by Maatoug. Yet Alyssa and her older sister Sarra are offered little exploration outside propping up Bessa’s male lead; a protagonist who is provided limited back story or understanding of who he is beyond a desperate, despondent street seller burning from the inside out.

Thankfully, Adam Bessa’s profound performance prevents Ali from simply fitting the angry-young-man trope. Of course, Ali does have the right to be mad; wearing dirty military fatigues and squatting in one of Tunisa’s many half-built homes that look like modern ruins, he represents the countless young men frustrated by the empty promises of successive governments and a revolution that fizzled out. Radio reports speak of high unemployment rates and “harkas” buying their way to Europe through illegal channels. As Ali struggles to make ends, Bessa articulates Ali's vexation with subtle-yet-highly charged movements; a furrowed brow here, tightening lips there, darkening eyes and so much weighted silence it becomes depressingly inevitable this poor guy is going to snap.

In Tounsi, the country’s Arabic dialect, “Harka” has many more meanings. “Movement,” “militia” and “to burn.” It’s a label that suitably represents Ali and the dream of a better life – incinerated by a society too willing to look away.